It has been ten years since Roberto Bolaño died while waiting for a liver transplant that never came; he would have been 61 years old this month and would doubtless have added to the body of work that includes such monumental novels as The Savage Detectives and 2666, though we might wonder how the latter would have been different had its writer not been in a ferocious race against death to complete it. Here, a translation of the great Latin American writer’s final interview, conducted by the Mexican writer Monica Maristain just before he died.

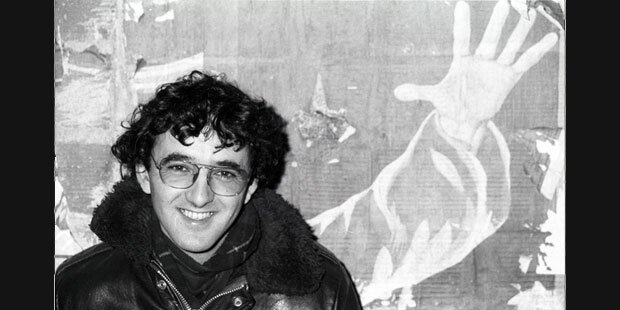

In the ill-defined panorama of Spanish-language literature, a place in which everyday young writers emerge more worried about winning scholarships and positions in the consulates than about contributing to artistic creation, the figure of a scrawny man stands out, blue satchel on the hip, enormous glasses, everlasting cigarette between the fingers, fine-tuned irony always at the tip of his tongue when necessary.

Roberto Bolaño, born in Chile in 1953, is the best thing that has happened in a long time to the writing profession. Since he made himself famous and pocketed the Herralde (1998) and Romulo Gallegos (1999) awards for his monumental “The Savage Detectives”, perhaps the greatest modern-day Mexican novel, his influence and figure have continuously grown: everything he says, with his cutting humor, with his exquisite intelligence, everything that he writes, with his accurate pen of great poetic risk and profound creative commitment, is worthy of the attention of those who admire him, and surely of those who detest him.

The author, who appears as a character in the novel “Salamina’s Soldiers”, by Javier Cercas, and who is honored in the latest Jorge Volpi novel, “The End of Madness”, like all brilliant men, divides opinions and generates bitter dislike despite his tender nature. With his voice between high-pitched and husky, he says — courteously, like all good Chileans — that he will not write a story for this magazine because his next novel, that will address the murders of women in Juarez City, is going on 900 pages and is still not finished.

Roberto Bolaño lives in Blanes, Spain, and is very ill. He hopes that a liver transplant will give him the strength to live with that intensity that those who have the good fortune to know him praise him for. His friends say that sometimes he forgets to go to medical appointments because of writing.

At the age of 50, this man who traversed Latin America as a backpacker, who escaped the jaws of Pinochet’s regime because one of the police that imprisoned him had been his schoolmate, who lived in Mexico (someday one stretch of Bucareli street will bear his name), who knew the Farabundo Marti political activists who would later assasinate the poet Roque Dalton en El Salvador, who was a watchman in a Catalan campground, a trinket salesman in Europe and always a good book thief — because reading is not just a question of attitude — this man has transformed the course of Latin American literature. And he has done it without warning and without asking permission, like Juan Garcia Madero had done,adolescent antihero of his glorious “The Savage Detectives”: “I am in the first semester of law school. I wanted to study writing not law, but my aunt insisted and eventually I ended up compromising. I am an orphan. I will be a lawyer. That’s what I told my uncle and aunt and then I shut myself in my room and cried all night”. As for the rest of the 608 remaining pages of the novel, critics have compared its importance to “Hopscotch”, by Julio Cortazar, and even with “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Bolaño would say, facing so much hyperbole: “Oh well. And so we better get to what is important in this situation: the interview.”

Did being born dyslexic add any value to your life?

None. Problems when I played soccer, I’m left-footed. Problems when I masturbated, I’m left-handed. Problems when I wrote, I’m right-handed. As you can see, nothing important.

Did Enrique Vila-Matas continue to be your friend after the fight you had with the organizers of the Romulo Gallegos Prize?

My fight with the jury and the award organizers was basically owed to the fact that they expected that I would support, from [home in]Blanes and blindly, a group I had not helped select. Their methods, that a young pseudo-poet and Chavez-supporter informed me of over the phone, looked too much like the dissuasive arguments from the Cuban House of the Americas. It seemed to me that it was an enormous error that Daniel Sada or Jorge Volpi were eliminated in the early rounds, for example. They said that what I wanted was to travel with my wife and children, something that’s totally false. From my indignation at this lie arose the letter in which I called them neo-Stalinists and something else, I suppose. In fact, they informed me that they hoped, from the beginning, to award another author, who was not Vila-Matas, and precisely whose novel seems good to me, and without a doubt was one of my candidates.

Why don’t you have air conditioning in your study?

Because my motto is not Et in Arcadia ego, but Et in Esparta ego. [I live not in Arcadia, but in Sparta]

Do you think if you had gotten drunk with Isabel Allende and Angeles Mastretta you would have a different opinion of their books?

I don’t think so. First, because those women avoid drinking with people like me. Second, I do not drink anymore. Third, because even in my worst drunken states I have maintained minimal clarity, a sense of prosody and rhythm, and a certain rejection in the face of plagiarism, mediocrity or silence.

What is the difference between a scribbler and a writer?

Silvina Ocampo is a writer. Marcela Serrano is a scribbler. The light years that separate them…

Who made you believe that you’re a better poet than novelist?

The level of embarrassment I feel when by pure chance I open one of my poetry books or one of my narrative books– I am less ashamed of the poetry.

Are you Chilean, Spanish, or Mexican?

I am Latin American.

What does homeland mean to you?

I am sorry to give you a cheesy answer. My only homeland is my two children, Lautaro and Alexandra. And perhaps, following that, some moments, some streets, some faces or scenes or books that are within me and that someday I will forget, and that’s the best that anyone can do with their homeland.

What is Chilean literature?

Probably the nightmares of a poet who is resentful, gray, and perhaps the most cowardly of the Chilean poets: Carlos Pezoa Veliz, who died at the beginning of the 20th Century, and was the author of only two memorable poems, but, yes, they were truly memorable, and that keeps us dreaming and suffering. It’s possible that PezoaVeliz still has not died but is dying, and that his last moment will be very long, right? And all of us are within him. Or at least all the Chileans are within him.

Why do you always take the opposing side?

I never take the opposing side.

Do you have more friends than enemies?

I have enough friends and enemies, all free of charge.

Who are your closest friends?

My best friend was the poet Mario Santiago, who died in 1998. At this moment, three of my best friends are Ignacio Echevarria and Rodrigo Fresan and A.G. Porta.

Did Antonio Skarmeta ever invite you onto his TV show?

A secretary of his, perhaps his maid, called me once on the phone. I told her I was too busy.

Did Javier Cercas share his royalties with you for Soldiers of Salamina?

No, of course not.

Enrique Lihn, Jorge Teillier or Nicanor Parra?

Nicanor Parra is above them all, including Pablo Neruda, Vicente Huidobro, and Gabriela Mistral.

Eugenio Montale, T.S Eliot, or Xavier Villaurritia?

Montale. If in place of Eliot were James Joyce, then Joyce. And if in the place of Eliot were Ezra Pound, without a doubt Pound.

John Lennon, Lady Di, or Elvis Presley?

The Pogues. Or Suicide. Or Bob Dylan. But, well, let’s not be fussy: Elvis forever. Elvis with a sheriff’s badge driving a Mustang and stuffing himself with pills, and his golden voice.

Who reads more, you or Rodrigo Fresan?

Depends. The west is for Rodrigo. And the east is for me. Then we tell each other about the books from our corresponding regions, and between the two of us it seems we have read everything.

In your opinion, what is the best poem by Pablo Neruda?

Almost any from The Residence of the Earth.

What would you have told Gabriela Mistral if you could have met her?

Mom, forgive me, I’ve been bad, but the love of a woman made me good.

And to Salvador Allende?

Little or nothing. The ones that have power (even for a short time) don’t know anything about literature, they only care about power. And I can be a clown to my readers, if I feel like it, but never to the powerful. It sounds a bit melodramatic. It sounds like the anthem of the fucking honest. But in the end that’s how it is.

And Vicente Huidobro?

Huidobro bores me a bit. Too much tralalalala, too much like a skydiver that falls yodeling. Skydivers are better when they fall enveloped in flames or are already flat on the ground because their parachutes don’t open.

Is Octavio Paz still your enemy?

For me, certainly not. I don’t know what poets would think that lived during that era, when I lived in Mexico. They wrote like his clones. I haven’t kept up on Mexican poetry for awhile. I reread Jose Juan Tablada and Ramon Lopez Velarde. I am even able to recite, if the opportunity presents itself, Sor Juana, but I don’t know anything about what is written by those, like me, who are approaching fifty years old.

You wouldn’t give that role now to Carlos Fuentes?

It’s been awhile since I’ve read anything by Carlos Fuentes.

What do you think of the fact that Arturo Perez Reverte is currently the most read author in the Spanish language?

Perez Reverte or Isabel Allende. It’s all the same. Feuillet was the most read French author of his era.

And the fact that Arturo Perez Reverte has joined Real Academia?

The Real Academia is a rathole of privileged smart asses. Juan Marse isn’t a part of it, neither is Juan Goytisolo, Eduardo Mendoza, Javier Marias, or Olvido Garcia Valdez. I don’t remember if Alvaro Pomboit is included (if he is, it must be a mistake), but Perez Reverte is there. And well, (Paulo) Coelho is also in the Brazilian Academia.

Do you regret having criticized the meal that Diamela Eltit served you? [In a column, Bolaño compared her vegetarian food to being kicked in the stomach]

I never criticized her menu. If that were the case, I would have criticized her humor, a vegetarian humor, or perhaps humor on a diet.

Does it hurt your feelings that she considers you a bad person after the incident of the ruined dinner?

No, poor Diamela, it doesn’t hurt my feelings. Other things hurt my feelings.

Have you ever shed a tear over the numerous critiques that you’ve received from your enemies?

Many, everytime I read about someone speaking badly about me I start to cry, I drag myself across the floor, I claw at myself, I stop writing indefinitely, I lose my appetite, I smoke less, I exercise, I go for walks on the sea shore, which by the way, is less than 30 meters from my house, and I ask the seagulls which of their ancestors ate the fish that ate Ulysses, why me, why me, me who has done them no wrong?

In hindsight, what is your best work in your opinion?

My books are read by Carolina [his wife]and then [Jorge] Herralde [the editor of Anagrama]and then I try to forget them forever.

What did you buy with the money that you won from the Romulo Gallegos?

Not much. A suitcase, as I recall.

During the time that you lived off of literary competitions, were there any that didn’t pay you?

Not one. The local Spanish governments, in this respect, are honest beyond a doubt.

Were you better as a waiter or a gift shop cashier?

The position I was best at was working as a night-watchmen at a campground near Barcelona. Nobody ever stole while I was there. I stopped some fights that could have ended very badly. I prevented a lynching (though willingly, afterwards, I would have lynched or strangled the guy in question myself).

Have you ever experienced fierce hunger, cold that pierces the bones, heat that leaves you breathless?

As Vittorio Gassman says in a movie: “Modestly, yes.”

Have you ever stolen a book that you didn’t like later on?

Never. The good thing about robbing books (and not safes) is that one can thoroughly examine its contents before committing the crime.

Have you ever walked through the middle of a desert?

Yes, and on one occasion, and moreover arm in arm with my grandmother. The old woman was tireless and I thought that we would never make it out.

Have you ever seen colorful fish under water?

Of course. In Acapulco, without going into detail, in 1974 or 1975.

Have you ever burned your skin with a cigarette?

Never voluntarily.

Have you ever carved a lover’s name in a tree trunk?

I’ve done much more obscene things, but let’s sweep it under the rug.

Have you ever seen the most beautiful woman in the world?

Yes, when I was working in a store in 1984. The store was empty one day and an Indian woman came in. She looked like and maybe was a princess. She bought some cheap necklaces from me. I, needless to say, was at the point of fainting. She had copper skin, long hair, red, and everything else was perfect. An everlasting beauty. When I had to charge her I felt very embarrassed. She smiled at me as if to say that she understood and not to worry. Then she disappeared and I never saw anyone like her again. Sometimes I have the impression that she was the goddess Kali herself, patron of thieves and blacksmiths, except that Kali was also the deity of assassins, and this Indian woman was not only the most beautiful woman on earth but also seemed to be a good person, very sweet and considerate.

Do you like dogs or cats?

Bitches, but I don’t have animals anymore.

What things do you remember from your childhood?

Everything. I don’t have a bad memory.

Did you collect figurines?

Yes. Figurines of soccer players and Hollywood actors and actresses.

Did you have a skateboard?

My parents made the mistake of giving me a pair of skates when we lived in Valparaso, which is a city of hills. The result was disastrous. Every time I put them on it was as if I wanted to kill myself.

What is your favorite soccer team?

None right now. Those that have been relegated to the second division and, eventually, to third and then to regionals until they disappear. The ghost teams.

Which figures in all of history would you have wanted to be like?

Sherlock Holmes. Captain Nemo. Julien Sorel our father, Prince Mishkin our uncle, Alicia our teacher, and Houdini, who is a mix of Alicia, Sorel and Mishkin.

Did you ever fall in love with neighbors older than you?

Of course.

Did girls at school pay attention to you?

I don’t think so. At least I was convinced that they didn’t.

What things do you owe to the women in your life?

A lot. The feeling of challenge and the high stakes. And other things that I won’t say out of respect.

Do they owe you anything?

Nothing.

Have you suffered a lot for love?

The first time, a lot, after that I learned to take things with a little more humor.

And for hate?

Even though it sounds a bit pretentious, I’ve never hated anyone. At least I’m sure of being incapable of sustained hatred. And if hatred isn’t sustained, it isn’t hate, right?

How did you win over your wife?

Cooking her rice. At that time I was very poor and my diet was basically rice, so I learned how to cook it in many ways.

How was the day when you first became a father?

It was nighttime, a little before twelve, I was alone, and since smoking wasn’t allowed in hospital I smoked a cigarette essentially perched on a ledge over the fourth floor. It’s a good thing that no one saw me from the street. “Only the moon,” as Amado Nervo would have said. When I went back inside a nurse told me that my son had already been born. He was very big, almost completely bald, and with open eyes as if asking himself who the hell was this guy that had him in his arms.

Will Lautaro be a writer?

I only hope that he’s happy. So it’s better if he becomes something else. An airplane pilot, for example, or a plastic surgeon, or an editor.

What do you see of yourself in him?

Luckily he’s much more like his mother than me.

Do your book sales worry you?

Not in the least.

Do you sometimes think about your readers?

Almost never.

From what your readers have told you concerning your books, what has moved you?

Simply put, readers themselves move me, those who still dare to read Voltaire’s “Philosophical Dictionary”, which is one of the most enjoyable and modern works that I know. I am moved by the strong youth that reads Cortazar and Parra, just like I read and try to keep reading. I am moved by the youth that fall asleep with a book under their head. A book is the best pillow in the world.

What things have made you angry?

At this point, getting angry is a waste of time. And, regrettably, at my age time counts.

Have you ever been afraid of your fans?

I have been afraid of [Spanish poet] Leopoldo Maria Panero’s fans, who, on the other hand, seems to me like one of the three best living poets from Spain. In Pamplona, during a tour organized by Jesus Ferrero, Panero was closing the tour and as the day of his lecture approached, the city, or the neighborhood where our hotel was, filled up with freaks that looked like escapees from the insane asylum, that, on the other hand, is the best readership any poet can wish for. The problem is that some don’t just appear crazy, but rather murderous as well. Ferrero and I feared that someone, at some moment, would get up and say: I killed Leopoldo Maria Panero, and put four bullets in his head, and in turn put one in Ferrero and one in me.

What do you feel when there are critics like Dario Osses that consider you to be the Latin American writer with the most future?

That must be a joke. I am the Latin American writer with the least future. It is true that I am one of those with the most experience, which in the end is the only thing that counts.

Are you curious about the book of criticism that your colleague Patricia Espinoza is preparing [Territorios en Fuga]?

Not at all. Espinoza seems to be a really good critic, independent of how I will appear in her book — I suppose not very well — but Espinoza’s work is necessary in Chile. In fact, the necessity of a new criticism, as we call it, is something that is becoming urgent in all of Latin America.

And what about the Argentine Celina Mazoni?

I know Celina personally and I love her. I dedicated one of the stories in “Murder Whores” to her.

What bores you?

The empty discourse of leftists. The empty discourse of the fascists I already take for granted.

What do you do for fun?

Watch my daughter Alexandra play. Have breakfast in the oceanside bar and eat a croissant while reading the newspaper. Borges’ writings. Bioy’s writings. The writings of Busto Domecq. Make love.

Do you write by hand?

Poetry, yes. The rest, on an old computer from 1993.

Close your eyes. Which of all the landscapes of Latin America that you have traveled comes to memory first?

Lisa’s lips in 1974. My father’s broken-down truck on a desert road. The tuberculosis ward in a Cauquenes hospital and my mother telling my sister and I that we should take a breath. One outing to Popocatepetl with Lisa, Mara and Vera and someone else that I don’t remember, but yet I do remember Lisa’s lips, her extraordinary smile.

What is paradise like?

Like Venice, I hope, a place filled with Italian men and women. A place that gets used and worn down and knows that nothing lasts, not even paradise, and that is the end and afterwards nothing matters.

What about hell?

Like Ciudad Juarez, which is our curse and our mirror, the uneasy mirror of our frustrations and of our infamous interpretation of liberty and our desires.

When did you know that you were gravely ill?

In ’92.

What parts of your character has the illness changed?

None. I knew that I wasn’t immortal, which, at 38 years old, you should already know.

What things do you want to do before you die?

Nothing special. Well, I would prefer not to die, of course. But sooner or later the fat lady sings, the problem is that sometimes she isn’t’ a lady nor is she fat, but much rather, like Nicanor Parra said in a poem, she is a hot whore, and that is something that can shake anyone out of their deathbed.

With whom would you like to meet in the hereafter?

I don’t believe in the hereafter. If it exists, what a surprise. I would sign myself up immediately in any course that Pascal was giving.

Have you ever thought about committing suicide?

Of course. On one occasion I survived precisely because I knew how to kill myself if things got worse.

Did you believe at some point that you were going crazy?

Of course, but my sense of humor always saved me. I told myself stories that made me crazy with laughter. Or I remembered situations that had me on the floor laughing.

Madness, death, and love– which of these three things have you had the most of in your life?

I hope with all my heart that there has been mostly love.

What things make you laugh your head off?

My own and others’ misfortunes.

What makes you cry?

The same: my own and other’s misfortunes.

Do you like music?

Very much.

Do you see your work like your readers and critics usually see it: The Savage Detectives at the top and then all the rest?

The only novel that I am unashamed of is Antwerp, maybe because it continues to be incomprehensible. The bad reviews that it has received are my medals won in combat, not in skirmishes with simulated fire. The rest of my “work”, well, it isn’t bad. They are entertaining novels. Time will tell if they are something more. For now they give me money, they translate well, they help me make friends who are generous and nice, I can live, and very well, from literature. To complain would be very unjustified and ungrateful. But the truth is that I don’t consider my books very important. I am more interested in the books of others.

Would you take some pages out of The Savage Detectives?

No. In order to take pages out I would have to reread it and that is against my religion.

Are you afraid someone would want to make a movie of the novel?

-Oh Monica, I’m afraid of other things. Let’s say: more terrifying things, infinitely more terrifying.

Is Silva the Eye a tribute to Julio Cortazar?

-Not in the least.

When you finished writing Silva the Eye, did you feel that you had written a story capable of being in the same league, for example, of House Taken Over (by Cortazar)?

When I finished writing “Silva the Eye”, I stopped crying or something similar. What more could I want than it to be similar to one of Cortazar’s stories, although “House Taken Over”isn’t one of my favorites.

What are five books that impacted your life?

-My five books in reality are five thousand. I mention these only as ground-breaking or as shameless promotion: Cervantes’ Quixote, Melville’s Moby Dick, Borges’ Complete Works,Cortazar’s Hopscotch, Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. But I must also note: Breton’s Nadja, Jacques Vache’s Letters, Jarry’s King Ubu, Perec’s Life, a User’s Manual, Kafka’s The Castle, and The Trial, Lichtenberg’s Aphorisms, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, Bioy Casares’ Invention of Morel, Petronio’s Satyricon, Tito Livio’s History of Rome, Pascal’s Pensees.

Do you get along with your editor?

Quite well. Herralde is an intelligent and often charming person. Maybe it would be more convenient for me if he were not so charming. The only certainty is that I have known him for eight years and, at least for my part, affection does nothing more than grow, as the bolero says. Although, maybe it would be convenient for me not to like him so much.

What do you say to those who think that The Savage Detectives is the great contemporary Mexican novel?

That they say it out of pity. They see me depressed or fainting in the public squares and nothing better occurs to them than a white lie, which for everyone else is the most suitable in these cases and it’s not even a minor sin.

Is it true that Juan Villoro is the one that convinced you to not call your novel By Night in Chile: Shitstorm?

Between Villoro and Herralde.

Who else do you take advice from about your work?

I don’t take counsel from anyone, not even from my physician. I give out counsel right and left, but I don’t heed any.

What is Blanes like?

A pretty town. Or a small city, with thirty thousand inhabitants, quite pretty. It was founded two thousand years ago, by Romans, and later people from everywhere stopped by here. It isn’t a rich person’s resort, but rather for the working-class. Workers from the north or the east. Some stay to live forever. The bay is gorgeous.

Do you miss anything from your life in Mexico?

My youth and the endless walks with Mario Santiago.

Which Mexican writer do you deeply admire?

Many. From my generation I admire [Daniel] Sada, whose writing style appears to be the riskiest, Villoro, and Carmen Boullosa, among the more youthful it intrigues me very much what Alvaro Enrique and Mauricio Montiel, or Volpi and Ignacio Padilla do. I continue reading Sergio Pitol, who writes better every day. And Carlos Monsivais, which, according to what Villoro told me, gave [Paco Ignacio] Taibo II (or is he the III or IV?) the nickname Pol Pit, which seems to be a poetic discovery. Pol Pit, isn’t it perfect? Monsivais still has sharp fingernails. I also really like what Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez does.

Is there a cure for the world?

The world is alive and nothing living has a cure and that is our fate.

In what, and who, do you have hope?

My dear Maristain, you push me again to the crude sandlot of my innocence, which are my native lands. I have hope in children. In children and fighters. In children that screw around like children and the fighters that battle as brave men. Why? I refer to Borges’ gravestone, as the illustrious Gervasio Montenegro would say, of the Academy (like Perez Reverte, mind you) and let’s not speak of this anymore.

What feelings does the word posthumous awaken in you?

Sounds like the name of a Roman gladiator. An undefeated gladiator. Or at least that is what the poor Posthumous wants to believe to give himself courage.

What is your opinion of those who think that you will win the Nobel Prize?

I am sure, dear Maristain, I will not win it, as I am also sure that some good-for-nothing from my generation will win it and not even mention me at all in his Stockholm speech.

When have you been the happiest?

I have been happy almost all the days of my life, at least for a little while, even under more adverse circumstances.

What would you have liked to have been if you weren’t a writer?

I would have liked to have been a homicide detective much more than a writer, of that I am absolutely sure. A string of homicides, someone that can return alone, at night, to the crime scene, and not be startled by ghosts. Maybe then perhaps I would have gone crazy, but, being an officer, that is solved with a bullet in the mouth.

Do you confess that you have lived?

Well, I keep living, I keep reading, I keep writing and watching movies, and like Arturo Prat said to the suicide-minded of the Esmeralda, as long as I live, this banner will wave.

Translated from Spanish by the students of Southern Utah University for International Boulevard.

Monica Maristain

15 Apr 2014