For one French expatriate living in China, the unpleasant reality sets in: he is not a particularly skilled worker, he is not living like a king among the natives, and China doesn’t really want him around anymore. The end of the Chinese Dream, for Westerners who thought they could live off the country’s boom, based on nothing but their native language: China starts to weed out the least useful of its immigrants.

Though Rue 89’s pseudonymous writer tries here for a note of wry self-criticism, his complaints have an uncomfortable edge of chauvinism. And he seems peculiarly blind to the fact that the Chinese government is merely enacting the kinds of restrictive immigration laws France and other European countries have long held over their own immigrants.

I have lived in China for more than a year now. It is a country with many exciting aspects. But it is not a country for just anyone, not anymore. Especially not for people like me, who love to travel for the joy of experience, for discovery, to see and understand and satisfy my curiosity.

I came here with my European ignorance, my image of China composed of fantasies about its rich culture and history, crossed with skepticism about a government that deals harshly with its own people. I am leaving slightly less ignorant.

China has become a kind of El Dorado, a bit like the USA of yesteryear. A place where you imagine you might achieve much, simply based on how fast the country itself is developing.

We imagine, despite being well educated, that we, as foreigners and strangers to the local culture, can just show up and act like settlers. A pinch of insolence here, a slice of luck there, and a bit of intelligence (maybe) and voila, we’ll create a life for ourselves here that we could only have dreamed of in France or elsewhere.

A dream that is perhaps still possible, but China has begun to apply its own rules-and rightly so. Slowly but surely, China has begun to select its immigrants based on a strict criteria: the country’s own needs. For those who lack the money, the ‘guanxi’ (connections), or particular professional skills of a medical doctor, engineer or scientist, it is becoming a real hassle to ‘just hang out’ in China.

If you are not armed with the skills or connections, the new immigration laws mean that you need a lot of guts, or a very good reason to stand up to the torture. For my part, I have chosen to give up the struggle. I do not fit into any of the above categories, and I cannot imagine fighting the system for a piece of a pie that I am no longer sure is worth having.

This September, a rumor starts going around: a new law on visas is being cooked up. But this time, it turns out to be more than just a rumor; something is actually coming down the pipe.

As in previous times, we start by panicking a little bit, and trying to find out more. Then we give up and face the facts: nobody knows anything. Because in China, nobody ever knows anything.

So we settle in and get used to it. Panic subsides into indifference. We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it, at the last minute, ‘Chinese style.’

But the law passes, and it is a bloodbath. It feels like you are living in a noir novel. Everybody is talking about somebody (although you never hear precisely who) that asked for a multi-month visa and got two weeks instead. And with no possibility of a further extension. So everyone runs back to his own network (yes, we all have our own little shortcuts into the visa system: an agency, a personal contact), but nobody can give you a straight answer. The only way to find out your own future is to actually go and request a visa renewal.

And here, you sometimes long for the French bureaucracy. China has the distinction of a 3,000-year-old bureaucratic culture that leaves you helpless before an implacable and unforgiving state.

Those without the good fortune to possess a work permit (a complicated affair), seize on the ‘business visa.’ In theory, a business visa is not supposed to allow you to work for a Chinese company. In practice, though, it is probably the single most-used visa for foreigners who work for Chinese companies.

Among the requirements for a work permit: a round-trip ticket to Europe, something most companies are not exactly thrilled to pay for, when they can instead buy a cheap short trip to Hong Kong or any nearby country. A certain number of years in college, coupled with a certain number of years of professional experience. A medical examination carried out in your own country. A letter of invitation from the Chinese government-which you must mail to the Chinese consulate in your home country. And in the end, even if you fulfill all of these requirements, there is no guarantee that you will actually get a work permit.

On the other hand, the business visa is as easy as it comes, and it allows you to think of yourself as being legally present on Chinese territory without being labeled a ‘tourist.’ Up until now at least, this was an easy visa to get: you just showed up at an agency with an I.D. photo and a business card and bam! The next morning, a visa. But not anymore.

From now on, they are regulating. No more short-term visas: if you cannot show a serious justification for a long-term visa (six months or one year), then you will get nothing. The employees at the consulate will tell you that you have stayed here too long renewing short-term visas. Instead of the two-month visa you have requested, they will give you two weeks. Telling you, in short: “thank you, now go home,” or else “go play by the rules like you were supposed to.”

At this point, holding your little booklet with its fourteen short days marked in it, you think it is time to review your situation. You could try to stay longer or you could start calculating the costs of living in China, compare it with the quality of life, and realize, as I have, that it is not worth it.

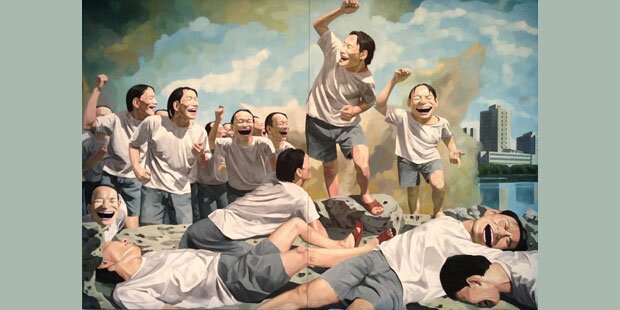

Face on the land. Yue Minjun.

Face on the land. Yue Minjun.

The Chinese middle class has caught up with you. You earn maybe a little bit more than the average salary here, but absolutely everything costs more for you. Especially the things that matter: rent and food. Because in China, prices are set based on how you look. If you happen to be blond, then everyone thinks you are an ATM. There was a time, true, when foreigners lived better than the locals.

But that day is past. Because on top of your (overpriced) rent and daily needs, you have this damn visa you’ve got to pay for. In the end, you live just the tiniest bit better than if you were in Europe, except that you live with the constant doubt of not knowing how long you will be able to stay: nobody remains in China indefinitely.

In China, they do not simply let things slide. You are not home here, and everyone makes sure you remember it. If you complain about being treated differently, you will be told: “This is China.”

I strongly advise you not to take out your frustrations on a local. You are not at home, and whatever happens to you, you will be in the wrong: this holds true no matter the situation (unless you have really good connections, or money, or irrefutable proof of what you are claiming).

After a while, you get used to it all-truly. You become calm, pacified. You stop looking for things to criticize. You have gotten past the crucial stage, of Made In China criticism. After all, you tell yourself, they have succeeded in developing a powerful economy, with strong growth; this country is constantly building, the standard of living is rising, and me, in the midst of all of this- I am just a lowly ‘laowai,’ a foreigner who is trying to get his piece of the cake.

The Chinese consider us, quite correctly, as people who are passing through. We have all come here to earn a living just because we can; and we can probably earn it better than they can. Nobody comes to China to be poor, or to take a job away from a local. You land here with an ambition, and eventually, you come to understand something: the only thing that keeps you here is the money. Bravo! You are now fully integrated into China.

This at least is the image that you end up having of yourself, given that the country has nothing else to sell to you, and you have a tough time justifying your presence here by a “love of Chinese culture.”

Because, if indeed the culture was your motivation, your hopes will be crushed, and you will end up like most foreigners who live here, with a superiority complex branded on your forehead.

“The Chinese are idiots. The Chinese don’t’ know how to walk. They don’t know how to drive. They don’t know how to behave, they don’t know how to be polite…”

The list goes on and on. To the point that half of your conversations end up being about what the locals have done to you, what they have done to each other, what they did at the office, in the metro, and so on.

Eventually, you will try to differentiate yourself:

“Oh, but I have some very good Chinese friends! Although they did go to college abroad…”

The person you are talking to replies with a knowing smile. “Yeah, I would have guessed.”

Yes, you will no longer be able to stand the ‘cultural’ differences-which are ‘cultural’ in name only. This is after all a society which in less than 20 years has gone from being deeply rural, to massive industrialization and hyper-consumerism. It has gone from being a third-world country to a superpower. “We have money, we don’t care,” some will tell you bluntly.

Their country has simply moved on faster than its people. Their parents and grandparents lived through starvation, epidemics, and other calamities. But you don’t think about any of this in the heat of the moment, when a stranger has sunk his elbow into your stomach in his efforts not to miss the metro (you never know after all, the next train may never actually show up): all you do is show your angry foreigner’s face, forgetting all about the analytical self that you were so proud of. He may apologize, or he may just ignore you entirely.

The landscapes are unbelievably beautiful. Or so they say. However, since you live in a city, and inside a compound for foreigners, you may never get to enjoy them. The only time you can go visit them is during Chinese holidays-the same dates for 1.5 billion people.

Which means the only place you will be visiting is your home country, unless you want to find yourself squashed in among one thousand Chinese and a few other foreigners lost like yourself among a dense and lifeless crowd, lined up on the Great Wall, a crowd from which you will only be able to extract yourself after some hours of struggle.

In the end, all you will have is your job, your ‘good’ salary and your anecdotes about the Chinese. It will be enough to draw your own conclusion: either you have failed in your Chinese Dream, or you arrived too late, or you are simply not cut out for this kind of dream.

You don’t want to end up being one of those racist and condescending expatriates. Nor do you want to end up being one of those blissfully assimilated expats who happily tells other foreigners how much he, unlike them, loves to eat the Chinese food, dripping in its oil, how much he loves Chinese culture, how he remains accepting and who never criticizes the locals or the government.

The first type is in no way superior, while the second is in no way assimilated: just like anyone else, if he dares to eat a Chinese meal from a street vendor, he will at best have a diarrhea, at worst an indigestion. But he will tell you the story of his adventure with a sparkling eye and an unquenchable admiration for the local culinary arts.

As for me, the feeling that remains is one of an immense steamroller that remorselessly crushes its own population along with the immigrants who wish to live here.

I have had the fortune to learn what racism and discrimination can feel like when you are on the receiving end. As a Caucasian, blond, francophone, born a provincial, I would not have been able to feel it to this degree in another country. I have to confess that it humbles me now to know how a simple gaze can be felt as an insult, how an obtuse question can feel like a personal attack that makes you want to erupt in anger.

Yes, all of this, I could never have experienced in France. China, on the other hand, teaches you to either become calm or to never be calm: you cannot fight against a human tide: you can only either let yourself be gently pushed around by the waves or drown trying to fight the waves.

I don’t want to hate China. There are certain things that are beautiful here, and there are certainly people who are remarkable. Unfortunately, whether it is my fault or theirs (or both), I refuse to lie to myself and pretend to like what I actually don’t, accept what I cannot accept, or pretend to be someone I am not.

To China, then, thank you and goodbye.

Further Reading: See our earlier Mapping Europe’s War on Immigration, with its accompanying cartography of the world’s rising barriers to migration.

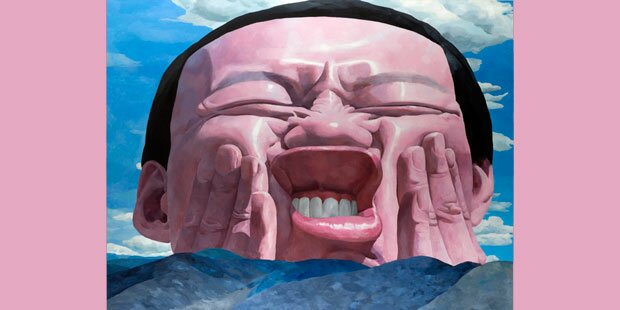

Face on the land. Yue Minjun.

Face on the land. Yue Minjun.