Power, masculinity, maybe a certain kind of ethnic pride: Taimoor Shahid writes that he is not entirely sure why he wears his problematic Pashtun beard in the educated middle class Lahore milieu he inhabits. But like a black teenage boy in a white suburb, he is noticed.

I

It is the check point of Lahore Cantt on Shami Road. I am standing there surrounded by soldiers in close vicinity: one to my left, one to my right, and one before me. I cannot see behind myself. Muzzles of three G3 battle rifles are pointed at me. One rests on my chest. Its metal barrel cold from the winter evening is tickling my skin. White search lights concentrated at me are not warming. I am panicking, of course. Sweating. Yet cold. Shouting too.

I haven’t done anything. I actually hadn’t.

I haven’t done anything. Please leave me. I don’t know anything. I actually didn’t.

I haven’t done anything. Please don’t kill me. Please don’t shoot. Please don’t kill me. Please don’t kill me. Please don’t kill me.

They are hacking at my clothes now. Panicked too. They are looking for something under my clothes. No they are looking for something under my skin. Kuch nahi hai. Mere pas kuch nahi hai. Nothing. I have nothing on me. Kuch nahi hai. Please don’t shoot. Please don’t shoot. Please don’t shoot. They did not.

I did not know I was afraid of death until I woke up shivering from this nightmare for the first time. Every time I had it again, I knew that death is scary.

II

It is the check point of Lahore Cantonment on Shami Road. I am going out of Defense Housing Authority, where I have started living a few months ago. All roads to everywhere lead through the Cantonment. Such is Lahore, if you live in Defense. Or not. This too is a nightmare. Except that it is not.

I am in a new car that I am not driving. A female friend is at the driving seat; another had called the shotgun; I am sitting in the back. Still, my masculinity is conspicuous in my haggardly beard and moustache. Normally, long tresses are a feminine trait in Pakistani imaginary, but when accompanied with a beard, they complement one’s manliness. Most certainly if you also happen to be in Lahore. Mine are performing the same function, my purple shirt and red pants notwithstanding. My friends too are dressed in a conspicuously middle-class manner. We certainly don’t seem to have jacked the car. Nor do I look like a kidnapper, thanks to the setting. But perhaps it’s my unmanliness that is evident, after all. What man sits in the back seat?

We are stopped. A soldier peeks inside and signals us to step in the extra security lane. There are a few cars ahead of us. We are waiting. It is our turn. Another soldier comes to the window, asks me to produce my ID which displays my name that starts with Muhammad and ends with Khan. The permanent address says Nazimabad, Karachi. I am asked what I am doing in Lahore. My friends are ignored. I show my work ID, and I’m let go. It’s routine exercise, which annoys a hell lot more out of my friends than of me. TS, always! Always! Every time I go with you, this happens! The implication, thankfully, is never that they won’t take me along the next time. Just frustration at being delayed.

III

Bhenchod tum darhi kaat kion nahi lete? Why don’t you fucking shave your beard? This will never happen again.

Why don’t you fucking change your skin color? This will never happen again too.

You have no sense of humour.

I have a beard on my brown shoulder.

IV

It is the checkpoint of Lahore Cantt near Mall Road. I am not lucky to have my friends with me. I am going home. I can afford a Rikshaw. But a Rikshaw cannot afford the security lane exclusively for cars. We are stopped, and asked to step in the extra- extra- security lane. Actually, it is not a security lane. It’s a wide area for poorer people: pedestrians, cyclers, bikers, and rikshawallahs. Rich people are not a threat to each other. They only fuck the poor—those in the by lanes. I am asked to get out. Eyes probe me, and my expensive looking clothes. I am asked to produce an ID.

What are you doing in Lahore?

I am a lecturer at LUMS.

Teachers are still respected. Or at least the ones that teach at the most elite institution of the country. The at least in the preceding sentence could very well be only.

V

It is my first month in Lahore. I haven’t gotten my first pay cheque. Rikshaws seem exorbitantly expensive. I take the paanch nambar No. 5 bus from Center Point to Defense. I am conspicuous with my red pants, blue sneakers, and a green shirt with floral patterns. I am uncomfortable in my clothes, so I decide to disappear behind my copy of an English book.

The bus goes through RA bazaar. Royal Artillery Bazaar, the abode of the Cantt’s underclasses where Defense goes to buy cheap supplies and domestic help. We stop at a checkpoint. A policeman enters the bus from the front door, several rows ahead from where I am seated. I glance at him and go back to the book. He comes straight to me and asks for my ID. I am baffled, but I do the needful. Where am I going? What do I do? Where am I from? Repeat routine. Then he goes to another man behind me, looks at his ID without engaging in a conversation, and gets off the bus. The bus starts moving again. I turn behind to look at the man. We commiserate in silent glances, then smile and shake our heads. We are the only men with beards on the bus.

VI

It is not a checkpoint. I have just crossed one. I am now in Gulberg. A friend drops me right before a new tea house in town. I sling my red canvas tote on my left shoulder, adjust my pakol on my head, and proceed to the entrance. I will secure a seat while my friend finds parking. I hold the door handle, pull at it to open the door, and suddenly a concierge runs up to me from nowhere, and gives me a start.

Sir, bag men dikhaa den kiaa hai? Sir, can I please check your bag?

I hand him my bag.

I’m a little annoyed, but he is clearly hesitant. Despite everything, my power over him is obvious. He is not oblivious to it. Concierge uniforms are not the same as [military]khakis.

He gropes through a mix of notebooks, two small water bottles, pens, pencils, markers, and heavy hardcovers of varying sizes strewn under a scarf and scraps of papers. Meanwhile, a few other men and women pass through the door. They too are carrying bags. One of them, a backpack. They are not asked to show their sacks. They do not have beards.

VII

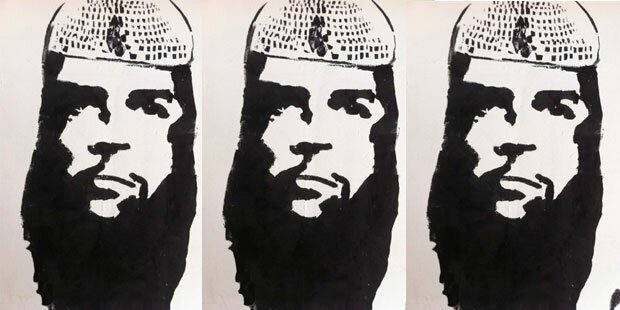

Pakol is a round warm winter hat made up usually of wool. It constitutes the attire of most men in North-Western Pakistan, and Afghanistan. It’s comfortable and stylish (or so I think), but it is Pashtun. Same is the case with the woolen wasket waistcoat.

I wear both often. They keep me warm. They’re inexpensive. And they are gifts from family in Peshawar. That is not why the villain in a popular play in Lahore is wearing it. Lou Phir Basant Aayi, Here Comes Basant Again, is the renowned and progressive Ajoka Theatre’s thirty-year commemoration play.

Lahore is under threat. Rogue elements are taking over the city. Love is impossible. So is flying kites. Normal life is obstructed. The social fabric of the society is being torn apart. Certain men are responsible for it. They all wear pakols and waskets. They have beards too. They just happen to look like Pashtuns. They are not Pashtuns. They are actors who don’t know how to act Pashtuns, like White men playing Black villains.

I am sitting in the big theatre on Mall Road. The show is boring, but I don’t want to leave. I have crossed a cantonment check point on my way here. It must be worth something. Finally, the villain enters, and says something. I hear khochi and the rest fades in the loud crowd cheer. In his pakol and wasket, he looks exactly like me. But he looks like nobody. He is a nobody. He is a pakol and a wasket. I am a nobody. I am a pakol and a wasket too.

Now I know what it must be like to wear a hoodie while Black. No, I don’t. I cannot. Nor can you know what it is like to wear a pakol and a waistcoat while Pashtun. Try it with a beard.

I leave the show midway. I am already thinking of the check point on my way back.

VIII

I have just passed my IDs silently to the sentry sitting inside the concrete vestibule at the Fortress Stadium checkpoint. He examines them under a torch while I silently stand and watch. He now knows who I am.

Sir yeh aap ne kia hulya banaya wa hai? Sir, what kind of a look is it, what have you done to yourself? Aap itney parhay-likhay hain, parhate hain, phir aisi darhi aur baal kion? You are well educated, you are a teacher, then why this beard and hair?

I smile back. I have never answered that question. Not even to myself. To be fair, I have never been asked that at a checkpoint either. Security officers are not interested in the ontology of your beard, neither in Lahore, nor at international airports.

I want to test the waters today. Should I do it? I hesitate, but proceed. I put a mellow smile on my face, hide behind it, and speak. It has become a crime to have a beard and be Pashtun. Bohat ziadti hai darhi waloun aur Pathanoun ke sath. It’s not fair to the bearded and the Pashtuns.

Nahi sir, yeh kia baat ki, main bhi Pashtun houn. No Sir, that’s not true, I too am Pashtun.

I am taken aback. I look at him carefully. I am looking for an answer. I can’t see him. It’s dark. But I see a khaki uniform. A beardless Pashtun with a crisp voice, and no pakol or a wasket. He also doesn’t say khochi when he speaks. Nor does he have the accent of the Ajoka villain I just escaped from at the theatre.

For some reason, I think of Malcom X’s Uncle Tom. Perhaps we can call him Uncle Khan in Lahore.

IX

I am at a huge bungalow on Zafar Ali Road. It is the annual music festival at the Sanjan Nagar Institute of Philosophy and Arts. It is delightful.

The concert ends with a beautiful Bageshri rendition by Debopriya Chatterjee, a flutist visiting from Chandigarh. It makes me happy. I want to show gratitude, but I am shy. I spot an organizer I know: my first Philosophy teacher. She’s also a music buff. I decide to go say hi.

Yeh aap ne kia Taliban jaisa huliya banaya hua hai? Oho, why are you dressed like the Taliban?

I never have an answer to this question. But on this occasion, this is my answer to another mystery. I can now explain the glaring stares of burly men in double-breasted gray suits. I now also know what they are doing at the venue. They are just missing khakis.

X

Masculinity is ferociousness. Ferociousness is masculinity. Flowers are not ferocious. Not ferocious are flowers. And thus those I wear in my beard all the time. Would you wear flowers in your beard too?

Taimoor Shahid

24 Aug 2015