Last week’s American air attack on a Syrian army convoy in the country’s southeastern desert passed largely unnoticed in the US media, but it suggests that Donald Trump and his generals are electing to shift to a strategy of long term geographic isolation of Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Syria’s civil war began in widespread Arab Spring demonstrations demanding that the country’s hereditary dictator leave office. But the uprising quickly evolved into an extraordinarily violent and sectarian conflict in which numerous outside players, from Turkey to Saudi Arabia and the US, sponsored rebel groups in various parts of the country. Meanwhile Iran, Russia and Lebanon’s Hezbollah have increasingly committed troops and resources to preventing Assad’s downfall.

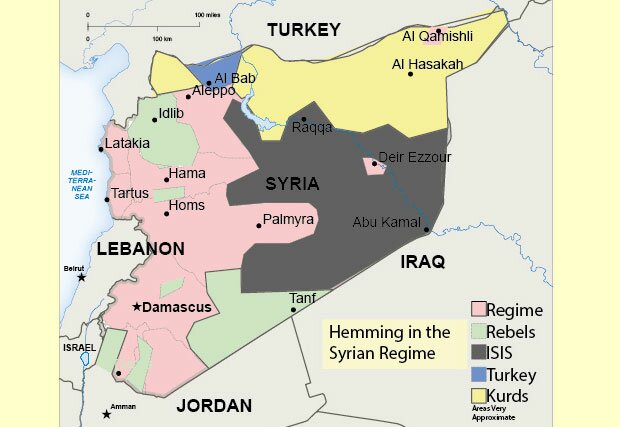

A couple of simplified maps of the Syrian conflict can help us understand both how the regime survived the war, and how its survival strategy may now trap it in a geographic cage of its own making.

The Syrian regime’s strategy during the civil war has been clear for some time: rather than try to systematically beat the rebellion throughout the country’s territory, Assad’s generals wisely elected to use their limited manpower to defend and where necessary reconquer a strategic “T”: the north-south line of major inland cities that stretches from Turkey down to Jordan, and an intersecting line out to the regime’s coastal heartland to the West. But the deserts of the east, the thinly populated farmlands of the north, the vast agricultural plains of the northwest: all these were more or less abandoned to ISIS, or to Kurdish leftist militants, or the motley collection of Islamist militias who now rule the rural central province of Idlib. Since Russia intervened in late 2015, the threat to the coastal heartland has been eliminated, and the regime has almost entirely solidified control of the chain of major cities where most Syrians live: Damascus, Hama, Homs, and Aleppo.

The regime’s strategic “T.” Map: International Boulevard

But meanwhile, the regime’s external enemies have been building fiefdoms outside of the strategic ‘T’: along the Jordanian border in the South, US and Jordanian sponsored Free Syrian Army affiliated groups control most territory outside of the town of Daraa (the small city which anchors the regime’s north-south axis of control). In the deserts of the east, the decaying Caliphate savagely holds onto what is left of its territory, hoping to keep places of retreat as defeat looms for it in neighboring Iraq. In the northeast, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units and their allies, with the help of vast American air power, have pushed ISIS out of an enormous strip of territory right into the suburbs of the Caliphate’s secondary capital Raqqa. And in the northwest, a three-way race for the city of al-Bab ended last year when the invading Turkish army and allied Islamist militants seized that city and the surrounding region from ISIS, beating an attempt by Kurdish militias from the East and west who sought to extend their control over the entire northern border with Turkey, as well as a late attempt by elite units of the regime to capitalize on ISIS weakness. Farther west, Turkey and Saudi Arabia are trying with less success to keep a semblance of authority over the militants who control the province of Idlib, but the al-Qaeda affiliated extremists there seem to be successfully absorbing all competitors.

Rhetorically, the militants who control these regions of the country remain committed to overthrowing the Syrian regime. But in practice, only the sectarian extremists who rule Idlib are still making the slightest effort to do so, with their occasional suicidal sorties toward Aleppo or Hama which inevitably end under a rain of Russian bombs.

Elsewhere, the armed rebellion is heading away from confronting the regime. The Kurds who dominate the country’s northern border are doubtless going to instead seek some strong form of national autonomy or independence once they finish off the existential threat of ISIS. Nominally, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (the ‘YPG’ for its Kurdish initials) are only a component of the American-sponsored Syrian Democratic Forces which will soon take Raqqa, but in reality they are the whole enchilada, and they have little interest in continuing the war once their own regional homeland has been saved.

Meanwhile, the wedge of territory that Turkey carved out of the north in its push to Al-Bab succeeded in splitting Kurdish territory in two, preventing Ankara from facing an uninterrupted wall of irredentist Kurds along its entire southern border (just across the frontier from Turkey’s own restive Kurdish region). Ankara has been very busy in its new exclave, training hundreds of paramilitary police, and supervising a gradual process of militant accretion, wherein its more disciplined Islamist proxy-forces absorb their weaker colleagues. The inevitable result will be the formation of some sort of Turkish proxy army in the area, turned to Turkish purposes rather than Syrian revolutionary purposes. Most obviously, Turkey will use it to threaten and attack Kurdish forces both east and west of the Al-Bab exclave, assuming Ankara can convince Donald Trump to betray the Kurds once ISIS is defeated.

So, the Idlib militants, the Kurds and the al-Bab Turkish exclave: what remains of the rebellion, other than the scattered and shrinking pockets in the country’s interior? Along the Jordanian border in the south, where the rebellion began, numerous units of the Free Syrian Army-who like to call themselves the Southern Front-hold most of the territory, including many large towns. They are trained and equipped by the Americans and Jordanians, but have never been able to mount a serious offensive against the regime. They have neither air power (Obama was never willing to directly attack the Syrian army), nor the endless supply of suicide truck bombers whom ISIS and the Idlib militants use in place of an air force.

Lines of control today. Map: International Boulevard

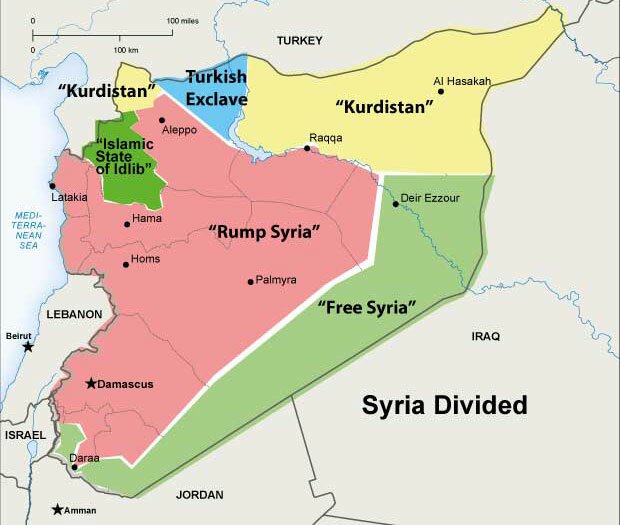

It began to become clear sometime last year that the regime was not going to be overthrown by the present actors in the conflict, that the defense of the strategic “T” had been successful, and that Assad and his clique were going to continue to rule over the ruins of Syria’s great cities, absent something totally unexpected. The Astana peace negotiations began, as the outside powers pushed their local factions and proxies to send representatives to an international peace conference in Kazakhstan. At that point the regime suddenly noticed that hostile powers and their proxies were solidifying control over its entire border (other than Lebanon and the sea), from Israel and Jordan to Iraq and all the way around to Turkey. Indeed, this was doubtless the main stick being waved at regime negotiators in the Kazakh capital.

The Syrian regime wants to open up corridors to the country’s borders – permitting land convoys of reinforcements and war materiel from Iran and Iraq and further afield. The shortest path to friendly territory happens to lead through the feeblest foes, the Free Syrian Army groups of the south.

The weakest of these forces by far is the small group of expensively-US trained and remarkably ineffective rebels in the Southeast called the New Syrian Army (recently retitled the Revolutionary Commando Army). Repeatedly humiliated in its minor skirmishes against ISIS, the NSyA must have appeared to be low-hanging fruit to Assad’s generals as the regime began to turn its attention to the suddenly clarifying geographic isolation that its strategic “T” defense was leading to. A little bit of heavy armor, a few hundred troops and perhaps some air support would have easily crushed the NSyA, allowing the regime to open a land border with friendly Iraq, and to its Iranian ally just beyond.

On May 6th the offensive launched, and proceeded apace along the desert highway to Tanf: little but a few gas stations and dry villages stood in the way; by the 17th, it seemed clear that the rebels were not going to be able to hold the area, that the task force of troops and allied militias was going to take Al-Tanf and probably start sweeping north along the Iraqi border through ISIS territory. And that was when the US stepped in and bombed the lead convoy, putting an end to what the regime must have regarded as an experimental thrust. For the first time, the US had provided air support to the Free Syrian Army (albeit justifying it with a claim to be defending American Special Forces operators deployed with the FSA).

It remains to be seen how determined the regime will be to open up a land corridor to Iraq. And it remains to be seen how determined the Trump administration will be to keep Assad’s regime bottled up in its strategic “T.” For example, what if the regime’s next thrust is farther to the north, through exclusively ISIS territory? Is Washington prepared for a sequel to the race for Al-Bab, a parallel race for Deir Ezzour (the besieged regime city on the Euphrates River where ISIS seems inclined to make its last redoubt)? The FSA proxies of the south hardly seem prepared to take on ISIS, even with extensive American air support, but the Americans would hardly be inclined to bomb the Syrian army while it was attacking ISIS (though it inadvertently did exactly that last year in Deir Ezzour).

In any event, the Astana Conference impasse seems to be where the situation is likely to remain: a Syrian regime solidly in control of the population centers of the strategic “T,” while insurgents sponsored by foreign powers calcify their positions in extensive territory along the country’s borders.

The American scenario for Syria? Map: International Boulevard

For better or for worse, this is a de-facto partition of Syria. At least one player in the Syrian war has long experience with that sort of thing: after invading northern Cyprus in 1974, Turkey systematically colonized the part of the island it had seized, ensuring that the partition would remain permanent. The Cyprus scenario may have been on Turkish government minds of late: reportedly Ankara has facilitated the immigration of tens of thousands of Turkish speakers into Idlib and northern Syria to build a loyal base of support and counteract Kurdish irredentism.

If the Syrian regime’s external opponents have their way, this might well be a map of the country’s future for a long time to come.

Jack Brown

27 May 2017