Narendra Modi’s Clean India Mission, and his focus on sanitation are central to the new prime minister’s push for a more modern looking India. Sanitation and anti-littering campaigns were a staple of postwar western countries, as mass urbanization and disposable consumer culture generated new mountains of waste that threatened to overwhelm the infrastructure that most cities had developed at the end of the 19th century. No surprise then that urbanizing India faces its own daunting sanitation problems. But as these essays from Hardnews make clear, caste attitudes, gender politics and other peculiarities bring their own obstructions:

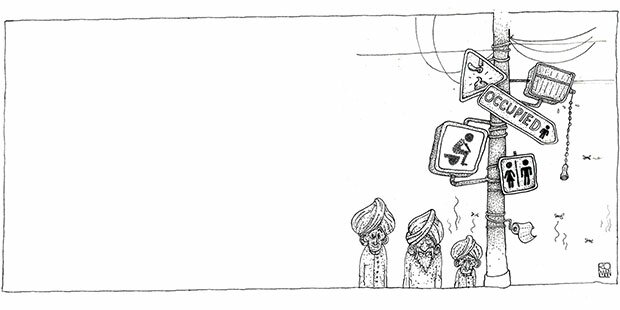

“A VAST SPRAWLING PUBLIC URINAL”

A hilariously dyspeptic essay on public urination, from Delhi journalism professor and former Hardnews editor Amit Sengupta: “New Delhi is the most miserable place I have ever lived,” a high-ranking Dutch diplomat told an Amsterdam newspaper a few years ago. He went on to describe the city as a hellish garbage dump, delivering these parting shots shortly before he left for a new post. His comments were translated by the Hindustan Times, and caused the predictable furor. Sengupta here reflects that in spite of its superpower aspirations, India seems to have little regard for its public spaces:

To pee is to be. That’s what we are, Hoo Ha India, superpower nuclear India, floating on public spectacles of yellow swimming pools of male piss, with condemned rivers of chemicalised filth and tonnes of garbage scattered like testimonies of greatness.

So what was wrong when a Dutch embassy official said that Delhi looks like a garbage dump? Why did our patriotic instincts get so aroused that we almost condemned this frank, free speech? Delhi is a non-biodegradable, backward capitalist, semi-feudal, patriarchal, uncultured garbage dump, why shy away from that? Not only that, Delhi has turned into a vast, sprawling, ever, macho public urinal, a shit hole, a faceless ghetto, an architect’s black-hole nemesis, an octopus without a soul or belonging or sensitivity or civic sense.

So what is so Mera Bharat Mahan about Delhi being a damned garbage dump?

Can’t you see it all over the place, from the posh, palatial south zones to the twilight zones of the east and west, with the demolished slums in between? Surely, even tinted windows of swanky cars are transparent, aren’t they? So why hide the gaze?

And where do the women go? The mother, the housewife, the working women? On the streets, in marketplaces, public parks, public transport, long distance roadways buses, flyovers, national highways —why are they condemned to hold on while men are all over pissing in stark daylight as if it’s a tide on a full-moon night. And where do you walk?

The slimy, stagnant, fragrant pavements are full of pissers in full public glory. The roads and highways are full of pissers. Not only the nooks and corners, they are all over the ideal city-state. The entire city has become a virtual reality of a public urinal—the stench floating like a cliché.

Except that the Delhi and central governments, the MPs, the MLAs, the opposition politicians, the ruling party politicians, the police, the mandarins in the municipalities, the Union ministers, the ex-ministers, the bureaucrats and babus, the elite— eyes wide shut, the page 3 party-types with colonial hangovers, the upwardly mobile and the middle mobile, the fourth estate, the real estate—no one is willing to see this masculine display of public patriotism.

Mass urinals as a tourist delight—welcome to this machismo capital of the power elite, the special dirty zone of organised filth and muck and gaseous, fungus-ridden waste and dirty waters.

When the masses are against hygiene and aesthetics, and when the men have no shame, and when the government wears a sanitised chastity belt of cold-blooded ignorance, who can stop this great pissing nationalism of our nationhood defined, even while we put pictures of gods on walls, stairs, pavements, residential areas to stop people peeing and spitting?

And if you think this is because Delhi is flooded by the unwashed, the slum dweller, the landless poor and urban worker, the low-middle class uncultured vulture, and that it is a demographic paradigm shift that is polluting its geography, think again, and look back with originality, if not anger.

That SUV, and not only with a UP or Haryana nameplate, its door half-open, its owner in a safari suit, doing it in the open courtyard of Pragati Maidan. Sometimes wife and daughter wait in the car till the man gives way to the basic looing instinct. This fascinating phenomena, truly, has broken all class barriers—the State has withered away and this philistine public piss joint is the only and ultimate utopia.

That’s why they are pissing on the Lodi crematorium walls even as the dead depart for their final journey, inside public parks post-Pranayam, outside schools even as children cross the footpath, on the Yamuna bridge, car and scooter waiting, as a mother walks away quickly with her daughter; outside the gates of the palatial homes of our MPs and ministers in Lutyens’ Delhi, outside hospitals like the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, where harried patients and their equally harried relatives wait for buses on the road under the sun because the state has chosen to build no bus shelters here since the last 20 years, on flyovers, parking lots, pavements and bus stops, talking on cell phones, bang in front of thosewaiting for a bus, while the bus waits and the pissers zip it up and walk into the ‘ladies only’ seats, proud and ugly like pea-cocks.

In any case, most clean, new pay-and-use toilets, barring a handful, are loaded in favour of advertisers in prime locations. Good planning, as they say.

In any case, Delhi has no public space culture, no benches where you can write a letter, no open-air modest restaurants where you can read a book and drink a black coffee or beer, no footpaths or stairs where a young couple can hang out and smoke.

Delhi hates its women, unlike Mumbai and Kolkata; women here are forever in danger of assault, physical, invisible, objectified, uncensored violence. Delhi is for the obscenely super rich, male and female, in affluent, sanitised, enclosed, air-conditioned, cocooned, protected zones, here they don’t smell the stench; Delhi is also for the male masses, lower, middle, upwardly mobile, downwardly mobile, the poor, the migrant, the exiled, the conquerors of the golden city, the pissers of paradise.

A swank car stops at Nizamuddin crossing. The door opens as a window rolls down, a prosperous man puts his chubby face out, and out flows from his mouth a huge chunk of red liquid, a paan’s remnants, and runs like a Persian carpet on the road. They are spitting everywhere, from bus windows on bikers, from truck windows on cyclists, from cars on pedestrians. If they could, they would piss from the windows.

They throw beer and coke cans, wafer packets, wrappers, plastic everywhere—the entire city is a bin. The city belongs to no one. No one belongs to the city. If you cheat me, I will cheat someone else. Me, mine, myself, who cares for Bhagidari? So why say, I love Delhi? Because Delhi is a sucked-up lollipop.

Delhi is polythene, all over, on trees, dhabas, shops, inside the choked-up intestines of our homeless, holy cows eating polythene with glass, plastic, leather, shoes, tin, aluminium, metal, used crackers, matchboxes, gutka packs in the garbage dumps. Gai hamari mata hai—the cow is our mother! So who will ask the Hindutva Godse Genius, if this is not cow slaughter, what is?

And where has the river gone? The pristine Yamuna at Yamunotri in the Himalayas, its magical origin, finds a magical metamorphosis at Wazirpur, in West Delhi, and becomes a divine nullah, a stagnant shitpot of millions, poisonous, full of effluents, garbage and chemicals.

The river disappears, the dirty nullah resurrects everyday, even as Delhiites stop their cars and throw polythene packets full of ritualistic Hindu flowers into the abyss of this abysmal degradation.

As I write this, thousands of Biharis are jumping into the half-white foam of this utterly filthy stagnation and celebrating Chatt in trans-Yamuna. So where did the crores of rupees spent on cleaning the river disappear? And what reflection can a narcissistic, consumerist, unaesthetic society find in the waters when it looks for its self-image? Shit. Our own shit.

Inside the water. Inside the ground water. Inside earth. Inside the food cycle. Inside the drinking water. Inside the intestines. Inside the mind. Shit. Our own shit.

Across Delhi, the new, green garbage containers designed by a genius dot the landscape like memorials. Except that dogs and pigs have found new homes, with the garbage spilling over and people jumping over them, like long jumpers in a nation with one Olympic bronze. So why spend crores on full-page ads asking people to protect themselves against the Aedes mosquito? The Aedes factory is right here, breeding, State-sponsored, all for free.

That’s what we are, Hoo Ha India, the superpower, nuclear power capital, floating on yellow swimming pools of male piss, with a condemned river of fossilised shit and chemicalised filth, and thousands of tonnes of garbage scattered everywhere, like grand testimonies of a clean, happy, healthy society. Like philistines becoming reformers. Like reformers becoming philistines.

Welcome to the capital city of power and pelf. The ideal State’s public urinal

– Amit Sengupta

THE SEWER DIVERS OF AHMEDABAD

Cleaning up human waste by hand, and assigning the task to a religiously defined caste is peculiar to India, and has proven to be a remarkably durable practice. Even in cities where public sewerage has been introduced, writes Lily Tekseng, society finds ways to continue oppressing the same people with the same foul work:

Sanitation in India cannot be separated from the ideology of caste. Traditionally, bolstered by the cultural logic of oppression, the lower castes have had to provide labour for all things considered polluting, e.g., cremating the dead, working with leather, disposing of waste and excreta, and so on.

To this day, ideas of purity and pollution coupled with the political economy of class inequality renders the task of cleaning and waste disposal solely on the shoulders of the lower castes and marginalised communities. According to estimates, out of the 1.3 million manual scavengers, 80 per cent are Dalits.

They often work with bare hands for little or no wages, face very high risks of occupational hazards and are systematically marginalised by society into a state of perpetual socio-economic exploitation.

Despite a series of legislation, ‘manual scavenging’ is still prevalent. Not only do private homes employ manual scavengers in dry toilets in many parts of the country but, more alarmingly, Indian Railways is responsible for employing among the highest numbers of manual scavengers in the country. This is in clear violation of the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act of 1993.

Besides being burdened with the unacknowledged task of being the essential component of the sanitation economy, the lower castes also have to deal with the lack of the very infrastructure of which they form a vital part.

The notion of defilement of water bodies by members of the lower castes prevents them from unrestricted access to water, thereby affecting their sanitary practices and health. According to studies, most public wells and taps are situated in the dominant caste areas and hence inaccessible to lower caste members.

Public sources of water therefore become spaces of conflict. Since the onus of household chores fall on the females of the house, it is often women who face verbal and physical abuse first-hand.

In large parts of the country where sewerage has been introduced, manual scavenging has been replaced by equally oppressive sewer cleaning practices. In an interesting case study of in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, Stephanie Tam traces the evolution of the labour provided by the Bhangis. The Bhangis were initially the caste that dealt in cleaning private dry toilets manually.

With the introduction of sewerage in the 1880s, the Bhangis were absorbed into the public sanitation system. It was both empowering and endangering for the community: it threatened their employment but liberated them from the demeaning labour.

Over the years, however, as Ahmedabad embraced capitalism and ushered in a modern notion of civic sense, the new economic system has done little to break the correlation between caste, class and occupation.

The working conditions in sewers include standing on an average of two hours in each manhole to clear blockages and the work is afforded no respect. According to a 2006 study, 45.4 per cent of Bhangis still do not have access to toilets or bathrooms, and in the modern economy, their unsanitary living conditions are used to justify their polluting and economically low status.

For many of the lower castes who have moved from private employment to being employed by the government in the sanitation economy, the authority that public institutions have in the psyche of the people has been counter-productive.

The appalling working conditions, their invisibility in government documents, minimal salary and lack of social respect is in a way a legitimisation by the state of the reproduction of old caste structures in the new labour economy. Also, the objective language of technology and development has made the perpetuation of caste exploitation seem necessary and logical.

The conversation about the relationship between caste and sanitation, therefore, must also encompass new ways of segregation and exploitation that is made possible by the primarily upper caste/middle class-driven notions of development.

– Lily Tekseng

THE FILTH ISSUE

Why, Lily Tekseng asks, is open-air defecation so persistent in India, when even poorer countries like those in sub-Saharan Africa have moved toward adopting toilets and sewerage as quickly as they can?

India’s biggest shame lies in how its people unabashedly conduct their excretory functions. “Most people who live in India defecate in the open. Most people worldwide who defecate in the open live in India,” says a paper co-written by seven scholars, including Diane Coffey, Sangita Vyas and Dean Spears.

Open-air defecation is a national activity, if inferences are to be drawn from the 2014 combined report by WHO and UNESCO, “Progress on Drinking Water & Sanitation, 2014”. According to the report, about 597 million people—i.e., roughly 60 per cent of the population—defecate in the open in India, a number so high that many scholars and sanitation workers have warned against a foreseeable human capital, health and gender crisis.

For a country where Gandhi lived and stressed the necessity of hygiene and sanitation, where the man himself is still revered unconditionally, his earnest prescriptions on sanitation and cleanliness are not taken very seriously. Often, people who defecate in the open think it is being more attuned with nature, healthy and, in rural areas, a good way to keep a watch on farms.

The correlation between public health and open-air defecation is not clear to the people who defecate in the open, especially in rural areas, where 67 per cent of families do not have access to toilets. Of those who do have access to toilets, at least one member of the family still defecates in the open.

The adverse repercussions of open-air defecation have been stressed time and again by sanitation workers and scholars alike. Earlier this year, the abduction and murder of two low-caste girls in Badaun, Uttar Pradesh, while they were on their way to relieve themselves in the fields at dusk brought attention to the vulnerabilities that females are subjected to in the absence of toilets. Threat of violence, shame, inadequate menstrual hygiene management and diseases become routine exposures in the lack of access to toilet facilities.

Owing to high population density, any area marked for open-air defecation cannot be too far away from human settlements, thereby exposing people to diarrhoea, enteropathy, physical and cognitive underdevelopment, and other communicable diseases. Children are the most vulnerable in this regard.

According to reports, 1,600 children under the age of five die every day in India, the highest number in the world. This has been termed as the “Asian Enigma”, i.e., despite relative economic prosperity and better progress in the factors that positively affect childhood nutrition, the nutritional status of children in South Asia is much lower than their counterparts in sub-Saharan Africa.

Some have traced the cause of the Asian Enigma to the status of women, illiteracy, and lack of childcare and nutritional knowledge. A recent study, however, draws a direct relation between open-air defecation and the Asian Enigma. Dr Dean Spears and his colleagues at the Research Institute for Compassionate Economics (RICE) have suggested that open-air defecation is directly related to childhood stunting and enteropathy. Stunting is an indicator of malnutrition and it is a public problem in India.

Indian children are marked by low birth-weight and subsequent growth despite economic and dietary improvements. Indian children are shorter on average than children in Africa even though people are poorer on average in Africa. Also, babies adopted from India into developed countries grow much taller.

Interestingly, it also explains the mystery of low child mortality rates in Muslim communities in India vis-a-vis Hindu communities, which are on average richer and more educated. The child mortality rate in Muslim communities is 18 per cent lower than among Hindu communities since the 1960s. Muslims are about 40 per cent more likely than Hindus to use pit latrines or toilets and also have Muslim neighbours who follow the same practice—a figure that explains the disparity in child mortality between the two communities.

India’s immediate neighbours have, on the contrary, witnessed a steady decline in open-air defecation. Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh enjoy a trend of decreasing open-air defecation (25 per cent and more, according to a 2013 WHO report).

Despite Gandhi’s earnest appeal and promotion of cleanliness and good sanitary practices, the Government of India only began an elaborate effort as recently as 1986, when the Central Rural Sanitation Programme (CRSP) was launched. It was soon followed by another sanitation programme, the Total Sanitation Campaign (TCS), also known as the Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan, in 1991; and in 2013, manual scavenging was banned in India.

Prime Minister Modi’s current Swachch Bharat or Clean India campaign has shifted the focus back on to sanitation by increasing the sector’s budget allocation and by calling on the private sector to actively participate in line with their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The Swachch Bharat campaign started on September 25, and has set the target of achieving (among a list of other things) an India free of open-air defecation by 2019—Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary.

The current government is ambitious regarding sanitation, but the challenges it faces are enormous. Owing to the urban pull factor and consequent migration, the number and size of slums and squat settlements are growing at an alarming rate.

This is not being met with adequate water supply, garbage disposal systems and access to toilets. According to the 2011 census, 13 per cent of urban households do not have access to toilets. Very high population density means that this has serious consequences, not only for people who defecate in the open, but also for all the other settlements in the vicinity.

While urban areas seem to be marked by a demand for toilets and other necessary civic amenities and their unfortunate lack, there seems to be sturdier resistance to toilet usage in rural areas. Centuries of traditional beliefs concerning purity and pollution manifest themselves more strongly in the rural areas, where people think it impure to have human faeces under the same roof as the home where they eat and sleep.

Soon after the government passed legislation against manual scavenging, many night soil workers complained about the sudden lack of economic opportunities. The classification of labour based on purity and pollution is still deep-rooted; the higher castes can’t imagine managing their own faecal output, and the lower castes struggle to adapt swiftly into a new economy.

People’s preference for open-air defecation was also highlighted in the study by Coffey, Vyas and Spears, et al. It has been found that Indians have an expensive concept of toilets—i.e., that toilets are expensive assets, even luxuries. For example, Haryana is richer than all the Gangetic states and, interestingly, also has more toilet coverage, according to a study.

Often, toilets are built to accommodate maturing daughters, new brides or old parents—more an affordable convenience than a necessity for the containment and disposal of faeces in order to reduce the proliferation of diseases. In contrast, countries much poorer than India, such as the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Burundi, Rwanda, Kenya, Bangladesh and Nepal are doing far better with regard to toilet accessibility, and their peoples show an awareness of the connection between open-air defecation and health hazards.

In Bangladesh, the building cost of a toilet is about `2,500 in purchasing power; in Indonesia, a country richer than India, it costs `4,492. In India, the government provides `10,000 to each household for toilet construction under the older scheme. However, most people in the north Indian states (where the survey for the study was done) quote the price for a cheap toilet as at least `21,000 on average.

Open-air defecation has long-term and serious consequences for a country’s human capital, which in the long run affect the productivity of the country. India has the lowest ‘middle rung’ population, i.e., the middle group who use unimproved and/or shared sanitation, as classified under international toilet standards (the lower rung comprising open-air defecation and the upper rung comprising improved sanitation). Bangladesh has 45 per cent of the population in the middle rung; sub-Saharan Africa’s middle rung is also 45 per cent of its population; India has only 16 per cent in the middle rung (something which has come to be called ‘the missing middle rung’).

The mission to eradicate open-air defecation and instate cleanliness must extend beyond photo-ops in which workers litter for ministers to clean up, and become more imaginatively engaged than merely increasing monetary assistance for each toilet.

Lily Tekseng

04 Jun 2015