Like a lot of the Turkish ruling party’s initiatives, it sounds like something ripped straight out of the Christian Coalition’s playbook: with the country’s schools in lamentable shape, Turkey’s Islamist AK Party has launched a school reform program that seems largely to consist of propping up religious schools and injecting as much religion as the constitution will allow into public schools.

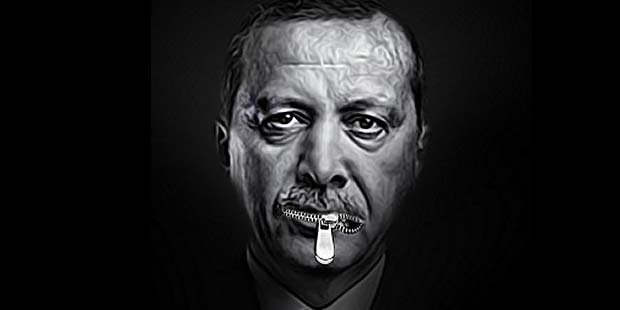

Progressive segments in Turkey have been going through trying times. The Islamic-leaning government which has been in power since 2002 has been riding roughshod over the principle of rule of law, using a failed coup attempt on July 15 as an excuse to suppress critics. The intensity of the crackdown on the country’s independent media and all opposition has become unbearable. As a natural result of the grim outlook, there are numerous reports from foreign countries indicating that an increasing number of Turkish citizens seeking a better life abroad.

Yet for average people who aren’t in professions (such as journalism or writing) that makes them an open target for the government, the long-term uncertainty of the country’s future doesn’t lie in the ongoing turmoil. Rather, it is rooted in the government’s persistent attempts to bring more religion into the country’s already flailing education system.

Turkey’s education system desperately needs to be reformed. The country ranks 35th among 38 countries according to the latest OECD Education at a Glance Report. It hasn’t done well in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) either. Among the 65 countries that participated in PISA in 2102, Turkey ranked 42nd in math, 45th in science and 41st in reading. However, any change introduced to the system in the past decade has appeared to have come out of an ideological agenda, rather than out of concern for improving the school system.

One example of a change introduced to the education system by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) was the division of education into three levels popularly referred to as “four plus four” in Turkey, which has effectively increased the enrollment rate in religious state schools called imam-hatips. Many regular high schools have also been turned into such schools. In the past 11 years, the number of imam-hatip students has gone up to 1.5 million from 71,000.

A more recent contentious move from the AKP government has been introducing its “project schools” scheme, announced by the Turkish Ministry of Education in 2014. With the plan, the ministry announced that it will be appointing the teachers of educational institutions designated as projects schools directly. 155 schools have been designated as ‘project schools’; about 100 of these are imam-hatip religious high schools and some are vocational schools. However, the remaining include Turkey’s highest-ranking schools, which have consistently produced the top-scorers in the country’s national university exams according to data from Turkey’s Student Selection and Placement Center ÖSYM. Both the students and staff at these schools have traditionally been placed at the end of a highly competitive admission process. Explaining its “project schools” project, the ministry said staff who have served at these schools more than eight years would be reassigned to other schools to benefit from their qualifications. In practice however,students at these schools have said the project school designation has ideological motivations. With the start of the school year in September, students at these schools started complaining of pious teachers or principals interfering with how they dress; banning festivals or exhibitions; or commanding them to end their friendships with members of the opposite sex. The new administrations at these schools have also welcomed visits from religious-minded groups. Most recently, an Islamist group was allowed to open a stand in Cağaoğlu Anadolu High School featuring an exhibition dedicated to praising the life of Mohammed, the prophet of Islam.

Hundreds of students from dozens of some of the country’s oldest and best schools protested the project school scheme, organizing sit-ins or turning their backs to principals. The government responded by detaining students and sending water-cannons to the schools where protests took place. The issues remains unresolved. Four alumni associations representing Kadıköy Anadolu, Vefa, Bornova Anadolu and İstanbul Erkek High Schools have joined forces to change the project schools directive.

Outside project schools, reports of harassment of students by newly appointed teachers has been rampant. In the past years, the AKP government has introduced optional courses on the life of the Prophet, and many local education directors have publicly expressed their distaste for co-ed classrooms. Authorities have turned a blind eye to obvious violations of freedom of religion. For example, on Nov. 18, residents at a park in İstanbul’s Güngören said posters reading “pray or you will burn in hell” were put up on lamp posts in a children’s park, and that the municipality had ignored their calls for their removal. Such encouragement also has had grim consequences. In a recent example, a high school student committed suicide after the school’s principal threatened her with dismissing her from school because she was sitting on the same bench in the yard with a male classmate.

The AKP’s education policy is in keeping with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s oft-repeated calls for marriage at early age and having many children. On Nov. 17, AKP deputies sponsored a bill that will allow men who have raped children go free. The bill was proposed a week after the Turkish government shut down 370 civil society organizations, which included a large number of women’s rights groups and a leading children’s rights organization.

The possibility of being detained or arrested in Turkey’s State of Emergency over sharing critical views online or even in conversation with friends, for most, is an immediate concern and it is very real. However, the government’s increasingly Islamist tone is causing many to lose hope over the long term; and what has been termed a “secular exodus” has begun. Even if rule of law is restored one day, it might be too late for the country to make up for the damage incurred by the current brain drain.

Baris Altintas

07 Dec 2016