Was there a better chronicler of the pitiless cruelty of Guatemala’s urban society than the artist Anibal Lopez? A profile of a provocateur, of the artist as thug and transgressor, by Sebastian Escalon:

Piglets are plentiful, on hog farms. But a piglet with a name, ‘Hugo,’ dressed up with a beautiful blue bow is something special; a pet, almost a person, a character like one of the three pigs who vanquished the wolf, or like the cartoon Porky Pig. Anibal Lopez, the controversial Guatemalan artist who died recently, knew this well. And it was he who brought ‘Hugo’ to Milan’s Prometeo art gallery where, over the course of several days, visitors could play with the piglet, feed the piglet, and stroke the piglet as if he were some grunting phallus mounted on four hooves.

And then, on the show’s opening day – the horror! – Hugo was slaughtered, gutted, baked and served up at the opening reception, to the great dismay and revulsion of all of those who had grown fond of him.

The work, which forces the spectator to confront the hidden cruelty of the world of the consumer, and confront his own hypocrisy, is an example of the venomous games that this artist subjected his audiences to.

Anibal Lopez occupies a place apart among Guatemalan artists. “The Missing Link,” the artist Regina Jose Galindo calls him. In Guatemala, he marks the hinge between modern art and the transition to conceptual art, which tends to be made up of actions, installations, and performances. Lopez heralds and embodies the generation of artists, writers, filmmakers and musicians who, with the end of the civil war in the middle of the 1990s, began to defy the militarized conformity of urban Guatemalan society.

There are only four or five national artists who are really known abroad, about whom books and theses are written. Lopez, who won the Venice Biennial contemporary art exhibition in the category of young artist in 2001, is one of them. An artist who makes use of all of the means at his disposition, even illegal ones, in order to attack the double standards and sentimentality of the public. His work creates discomfort, anxiety, and outrage, even among contemporary art audiences who are accustomed to and look forward to provocations.

“In Guatemala, there are excellent artists doing very good work,” says Thomas Laroche-Joubert, a French artist resident in Guatemala and an expert on trends in global art. “But if you go to Mexico, you are going to run across a dozen people like them, and in China, you’ll find a hundred people doing the same thing. But there are not even two Anibals.”

There are still misconceptions and erroneous and superficial interpretations surrounding Lopez’s art. Many are unable to see anything in his work beyond a series of increasing provocations, or they dismiss it with a definitive “these people don’t know how to come up with anything new anymore.” Others however, appreciate not only Lopez’s subversiveness, but also the sharp formal logic of his work.

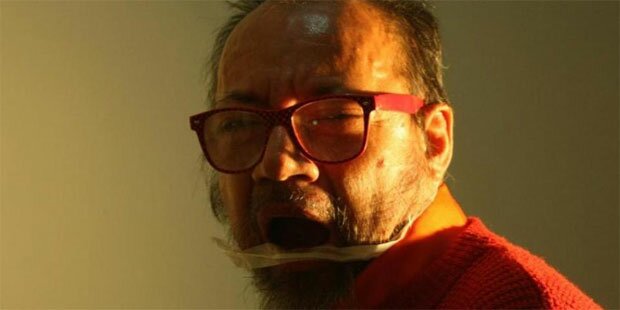

As for the man himself, there are probably similar gaps in understanding–between those who knew him little, and only in those final years when alcohol had transformed him into a kind of ill-tempered ghost–and those who knew him better, when Lopez was in full command of himself, who enjoyed his conversation, those who knew that in spite of his contentious and even perhaps conceited personality, he could be very generous and kind with those who mattered to him.

The artist Jorge de Leon remembers the evenings with him. “He would come to the house. We’d drink booze and talk. We talked about politics, cinema, music. As far as music went, he would listen to anything from Tigresa del Oriente to Beethoven, all the way through jazz and rock. They we’d get into visual art and eventually philosophy. It was dope, because it was confrontational.”

Leonel Jurucan, a writer who in the artist’s last years was his secretary, his nurse, and his wingman at bars, describes Lopez’s way of interacting with others as follows: “His motto was that everybody wants to walk all over you, and so he’d be very aggressive from the get-go. He would really piss people off, and he made more than one person cry. But if you stood up to him, and you had good arguments, you would win his respect.”

An artist who couldn’t stand beating around the bush, he made many of his friends think out their work more carefully. “Before I get started on a piece, I have to check and make sure Anibal hasn’t done it already,” says artist Jorge Leon. “There are works that I’ve abandoned because he’d already done them, and his were better thought out and executed. He makes me think more and try harder.” Regina Galindo, the Guatemalan performance artist, remembers: “Anibal was a philosopher. For me, he was an extremely intense learning experience, because he confronted me on everything. He wasn’t my teacher, but he was the closest thing to a teacher I ever had.”

Marginality always marked Anibal Lopez’s life. He was born in 1964 to a family from San Marcos, one of the first to homestead the vacant land in Mixco that is now the neighborhood of Tierra Nueva [in Guatemala City]. His father was a carpenter and an alcoholic, his mother a seamstress and a victim of the alcoholic who died young.

He had to fend for himself very early. His studies ended in middle school. As soon as he could, he migrated to the US as an illegal. He took jobs as a workman for a Mormon temple and a home remodeling company.

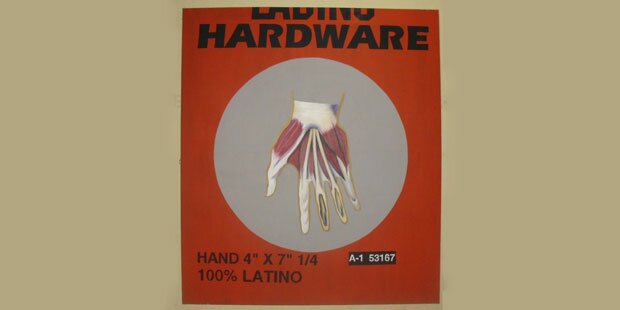

Returning to Guatemala, he enrolled in the National School of Plastic Arts (ENAP); his friends do not recall the exact dates of his studies there. To make a living, he worked for an advertising company and drew stickers for children’s’ albums with themes like “wildlife” and “the human body.” According to Leonel Jurucan, his later series “Ladino Hardware” which shows anatomical images of muscles in the human hand, resulted from this experience.

At ENAP, he was bored. Other than Dagoberto Vazquez, not a single professor there had anything useful to share with the students, he would later tell Rosina Cazali in an interview. He started hanging out with gallery owners, and with artists like Moises Barrios. His first solo exhibition, at the beginning of the 1990s, was planned to last only a single night. The owner of the El Sereno Gallery, in the capital’s Old City, could not stomach looking for any longer than that, at his collection of pictures of Saints, Virgins and Christs painted as if they were fashion models or style icons. “It was a way of mythologizing big brands, as well as a reflection on bisexuality,” the curator Rosina Cazali says of the show.

These were learning years for the young artist. Anibal was reading frenetically. Wittgenstein and Foucault became his writers of reference. “He realized the importance of readings and theory for an artist,” Cazali says.

His learning period culminated in Mexico, where he lived for a while with his first wife, the anthropologist Ligia Pelaez. There he became close to the dynamic artistic movements at play in Mexico City and became friends with the prominent Spanish artist Santiago Serra. “He came back to Guatemala transformed,” Cazali remembers. “He no longer would allow you to get away with a superficial analysis of artistic works. He was very confrontational, but he had the tools to be that way.”

Some forty or fifty people are present at the Los Cipreses funeral home on vigil with the body of Anibal Lopez. The majority are artists and writers. There is real sorrow here, a communion of pain and friendship unaccustomed among these people who are usually an archipelago of isolated egos. The writer Leonel Jurucan, one of those who seem most affected by the death of Lopez, is talking with the artist Yasmin Hage a few steps from the coffin.

“As artists, I feel like we are always being pushed to go farther, push the limits further, until we destroy ourselves,” Hage tells him.

“It’s true,” Jurucan says, a bit frenzied. “They want you to kill yourself. That’s what they want, for you to kill yourself to prove that all this shit is just not working.”

“Even between artists, there is a kind of callousness,” says Hage. “You can’t say this or that is very nice, because immediately they’ll tag you as corny or kitschy. Everything has to be hard, violent, dark. It feels like what they want is that you throw yourself out a window and document your corpse splattered on the cement.”

Lopez’s two young children chase each other through the hallways, tumbling over each other, fighting, complaining to their mother. Every once in a while they stop to peer through the window of the casket.

A group of Mormons cluster together in the chapel. A year before dying, Lopez and his partner Jennifer Paiz joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Every week they went to services. Anibal sang baritone in the temple’s choir. From the congregation they both received assistance that was very much needed given the declining health of the artist.

The Mormons are a powerful contrast with the crowd of bohemians. Water and oil. The believers sing hymns and praises in the chapel while the artists remain on the outskirts, in the outdoor corridors of the funeral home.

Abruptly though, the poet Simon Pedroza and the filmmaker Sergio Valdes burst into the chapel through the singers, as if determined to seize the lost territory. Pedrozo begins reading poems in his punk style, followed by Alejandro Marre, while Valdes flails on an out-of-tune guitar. The Mormons fall silent, waiting without complaint for the improvised performance to end, and when the poets and their audience retire from the room, lift their prayers again.

The next day, the day of the burial, water and oil continue not mixing. It is difficult to even believe that these two communities are here for the same interment. Lopez is buried in a tomb at the back of Los Cipreses cemetery. The dizzying Belice Bridge, behind it a mountain covered with farm fields, a highway snaking up out of the canyon, and the immense galleries of tombs arrayed under a sky of clouds charged with storm, all form a fantastical backdrop which would surely have pleased the artist.

There are speeches. Andreas, the oldest son of Lopez and his first wife, now a young man of 24 with an intelligent gaze, remembers that when they lived together, his father would ask him questions, and nothing but questions, instead of explaining or demonstrating things to him. Leonel Jurucan, between sobs, reads a short homage to the artist: “He has died like most of the great men who had the courage to love this country, broken, when they were not simply disappeared.” The Mormons sing a little bit, and their bishop offers some words that seem impersonal, as if he did not know the dead man very well. He even goes so far as to emphasize the ‘humility’ of Lopez; a humility which clearly formed no part of the dead artist’s defects.

Regina Galindo approaches the coffin. She pours out a bottle of whiskey on it. A bit of the liquor remains in the bottom of the bottle, and the artist slurps it down, weeping, before the unmoving gaze of the gravediggers. The Mormons will later complain to the artist about her sacrilegious and inexplicable behavior.

The 20th century draws to a close. Anibal Lopez has twice in a row, in 1994 and 1996 won the Paiz Biennial Art Exhibition. He could certainly keep on painting the canvases which have won him a certain amount of recognition in Guatemala. But no. He needs to seek out other mediums: he understands that painting “is not enough if you want to speak to people, it is not the most appropriate language to think and express yourself,” as he says in a 2011 interview with the Spanish Cultural Center.

A language that he does consider appropriate is that of ‘urban interventions.’ To his friend Leonel Jurucan he announces: “Well, they’ve signed the peace treaty. Which means that if we do things in public, they’re not going to beat our asses. Let’s demonstrate it.”

One of the demonstrations, perhaps the most extreme one, is carried out on the 30th of June, Army Day, 2000. At dawn, he spreads charcoal all along 6th Avenue, where the traditional military parade is going to pass. The charcoal is swept away before the parade, but traces of it remain, and the soldiers have to march over them. This work’s documentation, photographs of the parade and the boot tracks in the charcoal, are entered in the Venice Biennial and win him the Golden Lion in the category of young artist.

The work is an allusion, as the jury understands it, to the country’s devastated landscape, to its mass graves of burned corpses, to the massacres carried out by the same men who parade over it, swollen with patriotic pride.

Charcoal Stained Street, Army Day

There are other notable urban interventions, like the one called “One Ton of Books Dumped on Reforma Avenue,” in which a dump truck drops a ton of books in the middle of the avenue, obstructing traffic and inviting pedestrians to search out, in the heap, works of interest. The extraordinary “Ribbon of Black Plastic 120 Meters Long and 4 Wide Hung From Incienso Bridge” is his personal protest in 2003 against the participation of Rios Montt [former general and president convicted of war crimes]in the presidential elections of that year, a work which also recapitulates the living conditions of the neighborhoods that perch on the edges of the city’s ravines.

Systematically, Lopez attacks the moral values of Guatemalan society, demonstrating the country’s crudest and most violent sides. The climactic work of this facet of his efforts is “The Loan,” presented in the Context gallery in 2000. The work consists of nothing but a simple text printed on a vinyl sheet, which begins with these sentences: “On the 29th of September, 2000, I carried out an action which consisted of mugging [at gunpoint]a person of middle class appearance.” What follows is a description of the victim, Lopez’s modus operandi, and the amount robbed, 874.35 quetzales [$115]. It ends noting that the wine that spectators are drinking was purchased with the stolen money.

“In the face of the magnitude of this work, no one was able to even react at the time,” the curator Rosina Cazali, present at the opening, remembers. “’Now what, Anibal? Are you going to kidnap and murder us to make art?’ was the first thing anyone said, another artist. The work just transgressed all of the moral codes, and moreover turned all of the spectators into accomplices of a sort in the robbery.” On the subject of “The Loan,” Lopez says in his interview with the Spanish Cultural Center, that “The worst part was that no one reported it. People just drank their wine, and the wine meant complicity. Nobody is safe, least of all the artist. I feel that I offered up a sacrifice, because I still feel guilty [about this urban intervention], it still pains me, it was something really powerful, to say that an artist does not have the right to just get away with anything.”

“The Loan” also transgressed the formal codes of visual art: a simple text without photos or any other documentation affirming that a certain action was carried out. Whether it happened or not, nobody could testify. But nevertheless, the work stays fixed in the mind of the viewer, isolating him with his doubts and questions. What arises, according to Cazali, is an involuntary and perverse hope, like a fantasy, that the robbery really did take place.

With the rhythm of a machinegun Lopez keeps producing works and scandals. His actions and his pieces highlight certain aspects of the economy, like exclusion, or the possibility of hiring someone to literally any task. “The Dinner” (2000) involves a beggar having a meal in the gallery during the October Festival, served by an impeccable waiter from Altuna restaurant. “The Beautiful People” [titled in English]is a show watched over by security guards who only permit entry to people they consider good looking. In “Personal Defense Weapon,” (2005), a con man from the city’s central park sells stones to pedestrians with striking success, arguing that they are they are an effective weapon against crime. In “See You at the Top” [in English], a beggar walks around New York’s Wall Street wearing a sandwich board which in English says “See you at the top” and “Those Who Persevere Will Acquire.”In Lacandon (2006), an Indigenous man from the Lacandon jungle region poses for an entire day as if he were an object on display in a museum, next to a placard explaining what a Lacandon Indian is.

His work opens him doors at the biggest global contemporary art shows. A-1 53167, his identity card number with which he signs his work, as if trying to confound the very idea of identity, ends up becoming a recognizable brand in the art world.

His unmistakable figure, tall in stature, robust, with a salt-and-pepper goatee, thinning long hair combed back, enormous black plastic eyeglasses, becomes commonplace in large gatherings of artists. His works sell for 30 or 40 thousand dollars. He might have lived on his work in any great city. But he remains in his own country, land of his most deeply rooted hatreds and loves. He never stops being marginal. He affirms, loud and clear, that the national reality has no effect on him. He thinks himself unconquerable, invulnerable.

Guatemala takes charge of showing him how wrong he is.

“There are blows in life, so powerful…I don’t know!” The famous opening line of The Black Heralds by Cesar Vallejo well applies to the last years of Anibal Lopez. The fact is that in 2007, we find an artist at the height of his creativity, producing work almost without rest. That year, when he and Jennifer Paiz get together, Lopez is living and working with discipline in a well-appointed studio in the city’s Zona 9. Mornings, he jogs on the Avenue of the Americas, sometimes carrying a video camera to film the awakening city.

In 2008, something breaks in him. Lopez plunges into a profound alcohol addiction. “He had this new passion, alcohol, and his principal passion stopped being art. Alcohol changed him,” says Regina Galindo.

Life’s blows rain down one after another on the artist, deepening his depression and his addiction. First, there is the death of his father by alcoholism, which seems to mark him as already condemned to the same fatal destiny. Later a brother dies. Simultaneously there are anxieties brought on by another brother, a small-time drug dealer in Tierra Nueva who goes to prison and is then extorted mercilessly inside by gangsters. Lopez, with all the money problems already besieging him, pays again and again to save his brother’s skin. In 2012, just after being freed from jail, the brother is murdered in Tierra Nueva, his body dismembered and scattered around the neighborhood; a message. Lopez becomes the last surviving member of his family.

It is from this period that his show “Anthology of Violence” emerges; a series of handicrafts in clay that present scenes of daily life in Guatemala: hired killers firing on a bus; rescue workers extracting human body parts from a tunnel, a police patrol car smashing into a wall.

Money problems force the family, with three small children, to roam from place to place: cheap rooms, friends’ houses, hotels, a sordid tenement in front of the General Hospital. The artist disappears frequently, to reappear drunk lying on a sidewalk or on a hospital gurney. He drinks whatever he can; Jaguar aguardiente, rubbing alcohol, whatever his friends will give him. His health collapses. His work turns melancholy; there is a series of canvases painted in blood, vomit and feces, and another series called “Urban Trees” in which he paints, as if he were a novice, a series of humble, almost beggarly trees, isolated. It is a reference to a psychological test in which the subject is profiled by having him draw a tree. In one of them, the tree top is made with the business cards of gallery owners from around the world, as if trying to show the silliness of building networks of contacts.

In 2012, he is invited to the dOCUMENTA show in Kassel, Germany, the world’s most important contemporary art event, which takes place once every five years. For any artist, this is rapturous, the culmination of a career. Lopez, depressed, ill, with problems at home, is incapable of even enjoying the commotion his work causes.

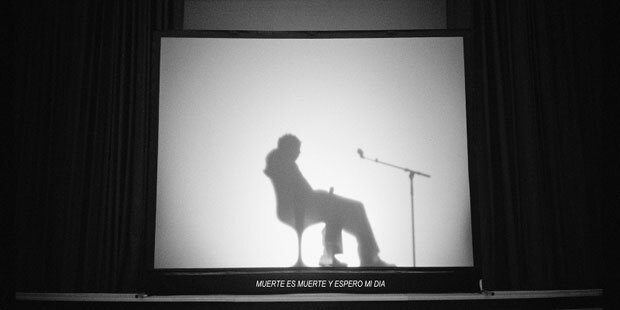

He brings with him to Kassel a hit man. “Testament,” the work’s title, presents the killer for hire behind a curtain which only allows his silhouette to be seen, to answer questions from the public. “Do you believe in God?,” “Do you enjoy your work?,””Do you have nightmares about the people you murder?” are some of the concerns that the killer responds to.

The work turns on its author. An hit man with whom Lopez had been in contact previously starts extorting the artist when he isn’t the one chosen for the trip. The family has to take refuge in a house Guatemala City’s old city, and later in a room in the Pasaje Rubio.

In spite of his illness, he does not stop creating, both pictures, as in the beginning of his career, as well as actions. His last action, in Italy, is a soldier manipulating a loaded gun in front of the public. He returns from this trip in bad shape.

A-1 53167 breathed his last on September 26, 2014. He approached life, art, and his contemporaries without making any concession. And he received in recompense no concessions. His death, his methodical and resolute self-destruction, perhaps was trying to tell us something as well; something dark, terrifying, insidious, something that is as present in the bars as it is in the churches, on the buses, in residential neighborhoods and down in the ravines, in the courtrooms and the maquila factories, and even in the art galleries.

Sebastian Escalon Translated from Spanish by International Boulevard

18 Nov 2014