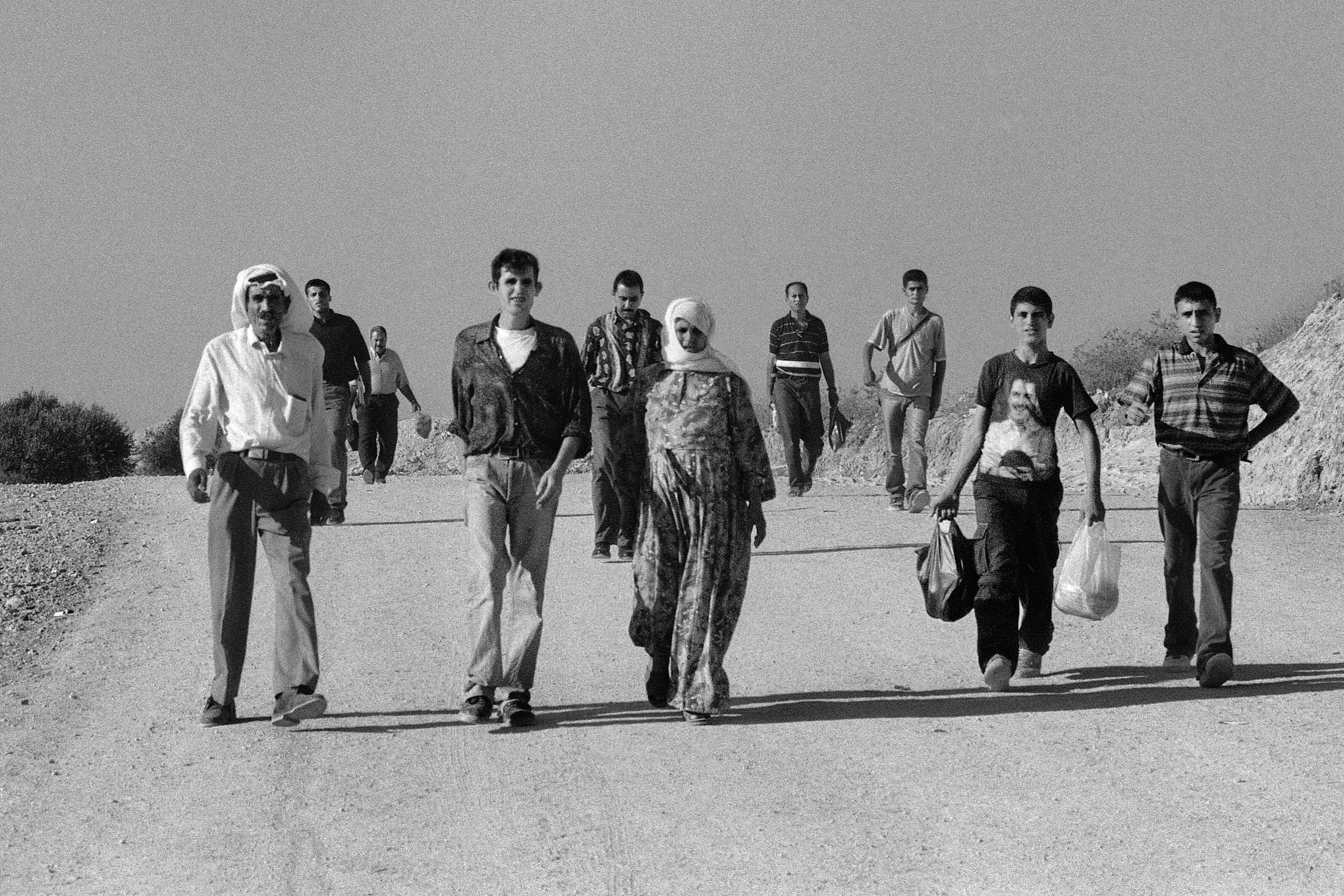

The latest round in Israel’s eternal war against Palestinian civilians seems to have ended in the usual fashion, with many dead, and with both sides enjoying new heights of public support. Lost as usual among the photographs of death and columns of smoke, writes Francoise Feugas, was a sense of the humanity of the people beneath the bombs. For that, she says, few photographers can match the lifelong work of Joss Dray. Images of the Palestinians, from Orient XXI:

Gaza is once more being bombarded. But the image that we are assailed with today, of a civilian population under siege, terrorized and at the mercy of violent Israeli military attacks, is not the one we find in the archives of Joss Dray, photographer and activist for Palestine since the 1980s. Her photographs reaffirm instead the humanity of a people who are resisting, ‘legitimate on their own land.’

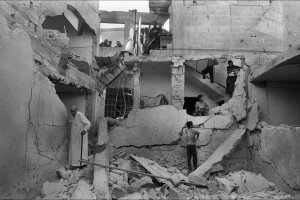

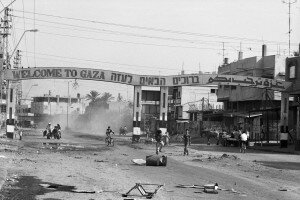

On the internet, endless photographs repeat the images of clouds of smoke rising above the houses of Gaza City and elsewhere. Gaza from a distance, just like in January of 2009, when Israelis as well as photographers from all over the world came to the frontier to watch the show as the missiles of Operation ‘Cast Lead’ fell.

We won’t find such images in Joss Dray’s photographs of Palestine. Because since the beginning of the first Intifada (in Dec. 1987), this longtime activist wanted to see, and allow others to see, ‘from within,’ the people of Palestine. “I am not a war photographer,” she says, by way of an introduction. “I need to meet people, find their humanity, their way of life, their culture.”

How did she end up in Palestine? She was active in the movement against the movement against American war in Vietnam and in the Third Worldist movement against imperialism and colonization. “So of course in the end Palestine was inevitable for me, it was logical,” she says. Photography was in the beginning a way of documenting the struggles of the 1970s in which she was involved.

One day in 1983, she telephoned the Palestinian newspaper Al-Yom Assabe’, just launched in Paris. She was hired immediately as a photographer and put in charge of the photo department. It was the second year of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, though she was not sent to cover it. “There are plenty of agency photos! We are not going to send you over there. Handle it yourself,” they retorted at the newspaper when, now in 1987, at the commemorations of the 40th anniversary of the establishment of Israel and the anniversary of the Balfour declaration, she decided it was time to go to Palestine.

So she went on her own, her mind filled with glorious images of the Fedayeen. On the spot however, it turned out that there weren’t any of them; she arrived in a country which did not feel like it was at war, in which people went back and forth with relative ease. “You could fly into Tel Aviv airport, and enter Jerusalem without any problems,” she says. “Between Israel and the West Bank, the border was completely open.” Troubled by the contrast between the idealized images of the combatants she had carried in her head, and the reality, she discovered “a people completely legitimate on their land, living together in a kind of gentle quietude in spite of the occupation,” she says. “That was in mid June. But when I came back in October, I could feel a kind of tension mounting. I still did not really understand exactly what was happening. It was only when I went back to Paris that I could see that it was the (first) Intifada.

To be a photographer is to find oneself “on the inside,” among the people, in a very close relationship with them, in order to see what they see, and to truly look at them. “During the first Intifada, there were sometimes 200 photographers on the ground. But all of them were with the Israeli army, and me, I was one of the rare ones on the other side,” she says. “I wasn’t just there to document the situation, but to retell the resistance of the Palestinian people.”

Joss Dray photographed the almost euphoric ambiance of the beginning of the Intifada, this uprising of all of Palestine, from the camps, to the cities and the villages. Photographs of women joyously heading out for the Friday demonstration. “And then the Israeli army kills someone at random, and everyone starts picking up rocks. And you watch the transition from joy to suffering. Each dead person is everyone’s son. For example, I photographed this murdered man, who had come from a village to demonstrate in the city of Ramallah. Right away, they find out who he is, they go back to the village, organize a funeral, come back forty days later for a memorial. This one man, he is the whole city of Ramallah, all of the villages.” Her first good photographs are taken there, and she says that it was only then that she became a real photographer.

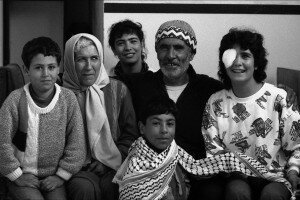

Resistance is everywhere, and in particular it is in the shadows, within the families whom she photographs in portraits. “The boys came down to kiss their mothers in the evenings, and returned to the mountains in the night. The suffering mother, in fear for her son; she is the one I photograph, she and the sisters.” The Palestinian people in all of their cultural setting, their humanity. Their beauty, she adds.

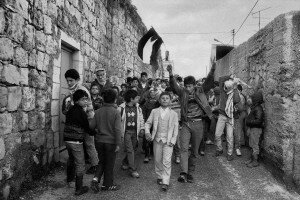

In those days, she says, they were “an over-photographed people. The photo-friendly “dance of stones” was in all of the newspapers. But it did not give a real sense of what this uprising represented. “You’d see some Kefiyyehs and a few flags, but you weren’t being told what it actually meant to bring out a [Palestinian] flag: it was a crime for which they were risking prison. So they were hidden in the houses; they only brought them out for the demonstrations. I have a very funny series of photographs where women pull flags out of nowhere and show them to me. There were even flags that the children would make with piece of cardboard attached to a stick, and colored with crayons.”

Dray stopped taking pictures between 1991 and 1993. “The Intifada unraveled, and my photographs with it, there was a blank moment” she says. She returned after the Oslo accords in 1994, to watch the arrival of Palestinian policemen, who came from the camps of Shatila, from Lebanon, from Tunisia, and who were welcomed by the population.

Gaza was transformed. Grand hotels were constructed, sidewalks were painted… “I found all of this a little bit sad, but I said to myself that this too must be shown.” Little by little, the partition was installed: the fences, borders and passages becoming more and more closed, violent and delimited. “Nobody was really taking pictures anymore, I was sort of all alone,” she says.

In the [Palestinian] refugee camps of Lebanon, she photographed terrible impoverishment, confinement and abandonment. Then came the second Intifada, which began in Sept. 2000. Would she this time have to resign herself to becoming a war photographer? The solution she chose was to continue to document this experience of life among the Palestinians, “showing a life with dignity and with the feeling of being at peace with oneself. [I wanted to document] everything that had not yet been destroyed by the Oslo accords, the political agreements that largely contributed in the dehumanized way people looked at the “other”, including the way Palestinians viewed the Israelis”.

The separation between Palestinians and Israelis was now total. How to tell that strange story? She chose to work with civilian organizations for the protection of the Palestinian people, who brought outsiders on the spot so they could see Palestine with their own eyes. “Clearly, this was an armed Intifada. But I continued to photograph those who chose other means of resistance, though in militant activities. In Jenin, for example, I brought photographs that I had taken during the first Intifada. Always with the strong desire to show people’s dignity and energy, I wanted to show through my photographs the immeasurable strength of the Palestinian people, who fight against being forgotten even while the work of society is being destroyed.”

Today, how does she see her work continuing? If she returned today to the West Bank or Gaza, or to the camps, what would she do?

“My son says ‘I grew up with two images of Palestine: the wound and the pride,’” she says. “The wound, that s the picture of a girl with a wounded eye, one that I showed at the Institute of the Arab World. Pride, that is the photo-one that has been very frequently re-used- of a demonstration by children, with a boy in a suit.” With her son, a cinema director, she plans currently to make a web documentary on the geography of Palestine – a geography a good deal wider, since it is abstract, than the narrow territories in which the Palestinians are these days imprisoned. “I would of course like to use my own archives, but I would also like to film, so that the Palestinians of today can tell us what it means to be part of the Palestinian people].” The first trip she would like to take, as soon as she can, would be to meet the Palestinian refugees recently forced out of Syria into Lebanon.

“They say that Gaza is where people have always been first to revolt, and especially that they have suffered the most. It is there that they continue to suffer. My archived pictures are a work that clearly show the history of the people of Gaza, of the refugees and of the wound that it is today.”

Francoise Feugas Translated from French by International Boulevard

03 Sep 2014