Sifting through the ashes of a murderous mob rampage that destroyed a small Christian community in northwest Lahore, the Herald’s Maham Javaid explores the history and the violent and difficult present situation of Pakistan’s tiny Christian minority.

When Martin Javed Michael reached Joseph Colony on the evening of March 8, 2013, he could smell fear in the air. The 116-house strong Christian residential neighbourhood in Lahore’s Badami Bagh area was eerily silent. The windows were boarded up and the doors padlocked. It was as if the residents of the colony had been warned of an approaching natural disaster and told to evacuate. But how can a padlock protect your house from a hurricane, wondered Michael.

As the head of the Pakistan Minorities Movement, a non-governmental organisation working to protect the rights of non-Muslim Pakistanis, he has been a frequent visitor to the colony and was friends with many of its residents. But, on that day, he could spot none of his friends there. It seemed that no one was around – except that Michael knew that there were people there, behind those boarded-up windows and locked doors. Some of them, indeed, had called him for help. Standing in the ominous darkness that had engulfed the neighbourhood, he looked around until he saw the familiar face of Liaquat Masih peeking through a window. Liaquat, who ran a machine-repair workshop on the main road outside the colony, let Michael into his house.

Liaquat was the only one at home; his wife and children had gone to his sister’s house in Shahdara, a working-class residential area several kilometres to the north of Joseph Colony. He quickly told Michael about the events of the last two days; then, heeding the urgency of the moment, they rushed to another house situated at the entrance of the colony.

The house at the entrance belonged to Saawan Masih. Outside it, on the main road running along Joseph Colony, lay a singed billiard table. A crowd had gathered around the remains of the table. Someone wondered how the table had been pulled out through the small entrance of his house; someone else asked why Saawan owned a billiard table in the first place. But no one asked the most relevant question: Why had the table been burnt? Perhaps because everyone knew the answer already.

Saawan, a 35-year-old sanitation worker with the municipal corporation and the father of three children, was being referred to as a ‘lad’ – this could have been because the elders of the community had seen him grow up over the years, so they still regarded him as a child, as most elders lovingly do. As Michael and the others talked about what could happen next, Saawan and his father Chaman Masih came out of the house. Under their breaths, everyone muttered that Chaman was doing the right thing: if he gave up his son to the police, then, the primary reason for the brewing storm would go away and Joseph Colony and its tense residents could breathe easy.

The local police, however, did not seem to think that way. Once at the police station, Michael asked Babar Bakht, the investigating officer, to call those who complained against Saawan, as well as those who had raced to Joseph Colony earlier that day after Friday prayers to hurl insults at the Christians and those who had pulled out Saawan’s billiard table to burn it. But the official refused. He told Michael that those people – mostly residents of Sheikhabad, a Muslim neighbourhood two streets away from Joseph Colony – were enraged and that no good could come out of inviting them for talks right now. Michael did not give up; he asked if Bakht could, at least, assure the Muslims of Saawan’s arrest. He was optimistic that the information would give them a sense of satisfaction. Bakht promised to do what he could.

The rest of Michael’s night was spent in or around the police station, convincing law-enforcement personnel to develop a channel of communication with the Sheikhabad Muslims. But as the night grew darker, fear among the residents of Joseph Colony became stronger. By dawn, they had realised that giving up Saawan had not solved the problem. The confirmation came when the police told them that they “should all leave until the situation calms down”. Officials at the police station warned them that their refusal to leave could “create a situation [that]we won’t be able to control”. But since they were promised that their houses would be protected, the Christians chose to heed the warning. Before long, every one of them had left Joseph Colony to join their families, spread across Lahore, in search of refuge.

They knew what could happen if they had stayed put. In August 2009, Christians living in Gojra, a town known for producing many world-class hockey players and located about 160 kilometres to the south-west of Lahore, had suffered a mob attack that torched and razed 40-odd houses and a couple of churches before burning an entire Christian family to death inside their house. The residents of Joseph Colony knew fully well that the police had done nothing to protect the Gojra Christians from the deadly attack. Indeed, the law-enforcement officials had stood by as the mob “took revenge” for an act of blasphemy allegedly committed a few days earlier at a Christian wedding in a small residential settlement outside Gojra town. It did not matter to the religiously charged crowd that the alleged blasphemers and the victims of the mob attack lived several kilometres apart.

Witnesses and media reports recount how a raging mob of several thousands, armed with clubs, automatic weapons and incendiary chemicals, ransacked the Christian houses, forcing their occupants to run for safety. The mistake that Hameed Masih, a resident of the colony, and his family made was that they refused to leave their house and resisted when the attackers came to burn down their house. This enraged the mob further and some of them, screaming insults and slogans charged the house, shot Hameed dead, bolted the main gate of his house from the outside so that no one could escape and set the modest dwelling on fire. Six people, including two women and one child, were burnt alive along with all the household furniture, utensils, family photos and other valuables. Two more Christians lost their lives before the mob was satisfied that it had exacted its revenge.

Four years later, an inquiry commission appointed by the government to look into the cause and the events of the attack has come up with a highly troubling finding: the allegations of blasphemy that had triggered the incident were baseless. It is ironic that not only did the Gojra Christians lose their lives, along with their homes and hearths, for something that did not even happen but also that no one was even sentenced for the financial and human losses that the ensuing mob attack resulted in.

The violence that erupted in Gojra was also not an isolated episode. It was, in fact, a repeat of what had happened in Sangla Hill town in 2006 and at Shanti Nagar – a Christian village a few kilometres to the east of Khanewal – in 1997. In all these instances, a mob inflicted instant ‘justice’ on entire Christian communities after perceived, manufactured and sometimes even imaginary incidents of blasphemy blamed on individuals.

Non-Muslims are spread across Pakistan in such a way that most of the Christians live in Punjab and most of the Hindus are concentrated in Sindh. Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa also house small communities of non-Muslims. Zohra Yusuf, the chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), explains how this geographical spread is a factor in why incidences of violence against non-Muslims are so common in Punjab. Non-Muslims living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan do not live in large residential colonies as do the Christians in Punjab, she says, suggesting that targeting an entire community is easier in Punjab where non-Muslim neighbourhoods stand out because of their size and exclusively Christian population. The other reason why mob violence against non-Muslims is not as common in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan as it is in Punjab is because the extremist organisations in these two provinces target Shia Muslims, who are more numerous and more concentrated there than the non-Muslims, she says.

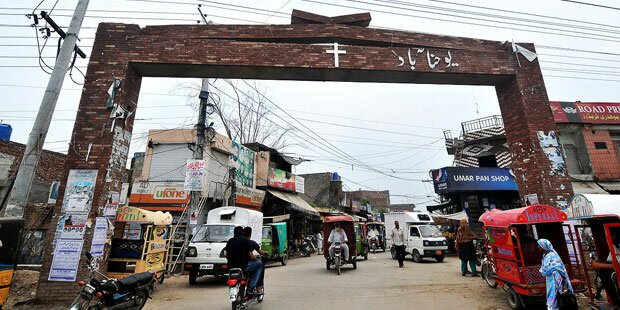

True to a large extent, Yusuf’s theory does not explain why Youhanabad – situated at the other end of Lahore from Joseph Colony, and is reportedly the largest Christian-only slum in the whole of South Asia, housing mostly sanitation workers and domestic servants – is seen as a safe haven by the Christian community. Ishtiaque Gill, a 23-year-old student of law and a resident of Youhanabad, is well-versed in the socio-political dynamics of this expansive residential area, mainly because he is sensitive to the exploitation and persecution that members of his community have to face in their everyday lives. The other factor behind his keen interest in the affairs of Youhanabad’s residents is his brother Tariq Javed’s involvement in electoral politics.

Javed was elected as a district councillor from the area, supported by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN). Gill’s own political sympathies waver between PMLN, Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and complete disenchantment with the political system, as he does not believe that the existing system of reserved seats for non-Muslims in the country’s legislative houses can benefit his community. This system, he says, has spawned Christian leaders who are beholden to the parties that nominate them for reserved seats rather than working for the socio-economic welfare of their community. He is equally unhappy with the religious leaders of his community who, he believes, are part of the reason why Christians in Pakistan are perhaps more backward than any other religious community in the country. “Just think about it, we have more churches than schools in Youhanabad,” he says. “Do you think that is the right way to progress?”

One thing about Youhanabad that stands out is that its residents seldom – if at all – complain of having faced discrimination at a personal level. This changes radically at the community level, though. There is not a single government school in Youhanabad while even small villages nearby, which house a majority of Muslims, sometimes have more than one government educational institution. The only education available is provided by private schools which charge as much as 2,500 rupees [$25] a month for each child studying there. A sanitation worker, earning anywhere between 10,000 rupees and 15,000 rupees [$100-$150]a month, often cannot afford such expensive education for his or her children.

Gill explains how the absence of government schools leads to another problem: since there are no government buildings in Youhanabad, no polling stations are set up for the thousands of Christian voters residing there. “Even though my brother is a political worker, he could not convince my mother to cast her vote, as she was too scared to leave the security of our neighbourhood and go to a polling station in a Muslim neighbourhood,” he says, with a sad grin on his face.

Deep in the winding streets of Youhanabad, there is a house that always stays locked from the inside. This is exceptional in a neighbourhood where doorways not only remain unlocked but even ajar, at most times of the day. Those living inside this house do not open the door to visitors without first thoroughly enquiring about their identities and the purpose of their visit. Ashfaque and Saima (not their real names) who live inside, have a reason for their caution: they don’t want anyone to know about them since this could endanger their lives. Fear, indeed, has haunted the two since they got married 16 months ago after Saima, a Muslim girl from a city in south Punjab, fell in love with Ashfaque, a Christian boy from Lahore. They had first met in a college in Lahore where they were both studying for their bachelor’s degrees.

When Saima wanted to convert to Christianity in order to spend her life with the man she loves, she was very scared. She had never heard of anyone do this before. As the two were making enquiries to find out how she could convert, her fear grew, since religious punishment for a Muslim converting to another religion is death. Since then, her fears have subsided but, every now and then, her husband receives life-threatening phone calls, forcing her fears to come rushing back to her. “I don’t think Ashfaque tells me about all the calls he receives. I think he wants me to raise our daughter in a sense of security,” says Saima as she rocks her four-month-old baby girl on her knee. She has not stepped out of her house since her marriage, except when she needed to visit the hospital.

Ashfaque knows of at least one more couple in a similar situation. “They are now in their fifties and it scares me to know that that they still receive threats via phone calls from complete strangers,” he says, but adds that he did not have much of a choice when he married Saima. “Humans have strengths and weaknesses,” he says. “One of our weaknesses is that we develop emotional attachments to people and then it is impossible to let go.” Ashfaque regrets his failure to complete his masters degree in law due to threats to his life. He, however, expects that he will be able to lead a secure life – mainly because of the fact that he resides in Youhanabad – “one of the safest areas that Christians can find in Pakistan.”

Next to Youhanabad, there is another Christian settlement, Asif Town. Its graveyard reached its capacity years ago. With help from local pastors and priests, the residents of the settlement have written many letters to the officials who lord over the departments in charge of graveyards. The only replies they have received are empty promises that the problem will soon be dealt with. “Meanwhile, we are digging out older dead bodies to make room for new ones,” says Pastor Younus Viklas, who runs a church in Asif Town. “I know it is horrific and unnatural, but what choice do we have?”

Viklas’s church is at the edge of Asif Town. In fact, it is the last building before the Muslim-dominated areas begin. Viklas, therefore, has to be very careful about the sound level of the church microphone. He makes sure that members of his church do not use the microphone during the week unless there is an emergency. Even during the Sunday service, he does not turn the volume up so as to avoid upsetting the Muslims living nearby. There have been complaints in the past.

A few months ago, Viklas wanted to build a toilet in the church for women and children attending service. He collected money from the churchgoers and engaged a builder to design and build the structure. But the construction had to be stopped only a day after it had started. The Muslims living across the road from the church complained that the digging required to lay down drainage pipes for the toilet would “disrupt their lives”. In normal circumstances, government intervention could have resolved the problem to the satisfaction of both communities, but these were extraordinary times. “The Joseph Colony incident had just happened and we had to think of our lives before thinking about our convenience,” Viklas says.

Youhanabad, Lahore, 2013. Photo White Star

Youhanabad, Lahore, 2013. Photo White Star

One reason why the attack on Joseph Colony caught its residents and Christians living in other neighbourhoods in Lahore by surprise was because the city had never before experienced such an attack. Non-Muslims living in Lahore may have always felt left out socially, economically and politically but their residential areas were never targeted in the past, says Michael.

The other reason for their surprise was that the whole incident started as a personal squabble between Saawan and his Muslim friend, Shahid Imran, who lives in Sheikhabad and works as a barber. The two had been friends for almost a decade. Many residents of both Joseph Colony and Sheikhabad remember how close Saawan and Imran once were. Humeira Iqtidar, a lecturer at King’s College London who spent many weeks in the two neighbourhoods, after the incident took place, relates that even their families were close as Imran’s wife and mother often spent their days at Saawan’s house, when they visited from out of town.

Shaheen Tariq (also known as Aunty in Joseph Colony) confirms Iqtidar’s statement: “Saawan and Imran were not just ordinary friends. They shared a deep relationship,” she says. “You don’t drink together every night if you don’t enjoy each other’s company,” she adds. Tariq has lived in Joseph Colony all her life and has been running the Tariq Karyana Store, a grocery shop that has been in the colony for more than a decade. She recounts how Imran and Saawan would often crack crude jokes while purchasing snacks from her. “All friendships have room for jokes and Imran and Saawan’s friendship was no different,” she says, but adds that she always warned them to be careful because jokes could easily be misconstrued. The two young men always told her not to worry.

Tariq’s shop is just two shops away from Saawan’s house. From that vantage point, she saw the initial stages of the attack unfold in front of her eyes. First, there were only three boys, all from Sheikhabad, who came there and began challenging Saawan to come out of his house and “face the consequences of his actions”, she says, describing the start of the events of that day back in March. Soon the crowd outside the house started growing bigger by the minute, and scores of people started cursing Saawan and his family.

Tariq’s shop had never been busier and, at least initially, she was delighted to see her sales grow, even though she was feeling a little uneasy about the commotion. Out of curiosity, she started asking her customers as to why there was so much screaming, shouting and name-calling. They told her that Saawan had made fun of Islam. Among the mob outside in front of her shop, she could spot Ghazali Butt, a PMLN leader, and Asad Ashraf, a former member of the Punjab Assembly, along with many men in green turbans. Their presence was reassuring for her. “These are influential people; they will control the crowd and everything will fizzle out,” she recalls telling herself. But the crowd pulled out Saawan’s billiard table to set it alight. She saw two young men purchasing petrol from a nearby shop for the purpose.

By that time, people inside her own house had started panicking. When she tried to dismiss her daughter’s pleas to close down the shop and run away, the girl yelled: “They are not thinking straight. They will break your head if you don’t shut down the shop.” It was at this moment that Tariq’s eye caught a glimpse of the fire being lit just a stone’s throw away from her shop. She pulled down the shutters, grabbed as much money as she could from the cash counter and ran inside her house. Little did she know that those 8,000 rupees [$80]would be the only thing she could save from her shop. Though the police managed to disperse the crowd that day, most residents of Joseph Colony knew the worst was yet to come.

According to the Human Rights Watch, an international organisation that conducts research and advocacy on human rights, living conditions for Pakistan’s non-Muslims have drastically deteriorated. Moreover, it stated in its 2012 report that Pakistan has been a “country of particular concern” since 2002 as far as the state of its non-Muslim citizens is concerned. Many in Pakistan, including some members of the non-Muslim communities, still want to believe that the situation is not as bad as it is made out to be. […]

Across the road from Joseph Colony, Mohammad Iqbal runs a small eatery. His three employees, all young boys from different parts of Lahore, describe him to be so devoted to his job that he comes across as a slave-driver. “Asking the boss for an extra holiday is like asking to get a slap across your face,” says Ahmed, who has been working at the food stall for two years now. But, a day after the Joseph Colony attack, Iqbal shut down his eatery and did not reopen it for almost a month. He says he was too scared to come to work. “In those days, the police were rounding up suspects involved in the attack. If I had come to work then, I would be in jail right now,” he says.

If fear of the police was not enough trouble, Iqbal was left scarred by what he saw on that fateful Saturday morning. He was serving breakfast to his customers when he saw a mob approaching. He is not sure how many people were there in the mob; he just says they were too many to count. “As far as I could see, there were people carrying sticks and stones,” he says and recalls how he told his staff to turn off the stoves immediately, drag all the utensils and furniture inside and drop the shutters. “I don’t know anything else. I was only interested in saving my shop and my life,” says Iqbal.

But Iqbal had seen more than others because by that time, the residents of the colony had all left; women and children had been dispatched the night before and the police had chased away the men left behind. The police is said to have told Muslim workers employed in the warehouses in the area in advance to not come to work that day. Another account suggests that the police forced warehouses workers to leave an hour before the incident.

The rest of what happened on March 9, barring photographs and videos available on the internet, is hearsay. Media images show the mob setting fire to shops and houses in Joseph Colony, throwing furniture from rooftops, and celebrating their revenge on the alleged blasphemer and members of his religious community. The most disturbing photographs are those in which the mob, wielding sticks, rods and assorted pieces of broken furniture, poses for the camera with wide, beaming smiles and victory signs flashing in the foreground.

While watching the videos showing the mob looting valuable and burning down whatever they could not carry away, one wonders where the police were and what they were doing to stop the mayhem. “They stood on the sidelines and watched,” says Michael.

Other residents of the colony wonder why the government did not order the rangers or the military to control the situation, if the police were unable to handle the mob. “It was not due to a lack of competence; the police stood by due to a lack of will,” says HRCP’s Yusuf. If they had the will, they could have tried to disperse the crowd by firing some teargas shells, she adds. But, according to Yusuf, this was not the first time that law enforcers had allowed their religious bias to supersede their professional duties. “Even during the riots in Gojra, the police did not fulfil their duties,” she says.

For Pastor Liaquat Masih, the police are capable of much worse than just watching a crowd on the rampage from the sidelines. Well-respected in his Isa Nagar village on the outskirts of Lahore, he doubles as a priest and a brick kiln worker along with other members of his family. His wife has developed calluses on her soles from kneading mud to make bricks. “We start work at 4 am and then take a break at noon, when the sun is too hot to bear,” she says. Their survival depends on how fast they can work. They get 500 rupees [$5]for every 1,000 bricks they knead, mould, dry and then bake. When they were younger and fitter, Liaquat and his wife could make up to 1,000 bricks in a single day. Older and always under debt, these days, they never find their earnings matching their needs.

Things were not always this bad, Liaquat laments. When he first moved closer to Lahore from a far-flung village in Punjab, he was pleasantly surprised to learn that he did not need to bother about his religious identity in the city. He was just like anyone around. But in the last five years, his religious identity has posed such problems for him that he often wishes that he could repay his loans and move back to his village. The latest source of his problems is a recent incident of robbery that occurred in Gujjumata, a village on the southern edge of Lahore. A day after the robbery, the police came to his house and took away his son, Sarwar Masih. A day later, the police came back and, this time, took away two more of his sons, Nadeem Masih and Patras Masih. “They kept them in custody for a month and tortured them every day,” Liaqat says. He had to borrow money from the owner of the kiln to bribe the police to get his sons released.

But the boys had hardly been home for a day when the police returned and took away Liaqat’s brother, Mushtaq Masih, accusing him of stealing a motorcycle. “Since then, I don’t let any of my boys sleep at home. We all sleep in separate houses because we are scared that the police may come any night and take all of us away,” says Liaqat. When Mushtaq returned home after a week in detention – but not before Liaqat had bribed the police again with money borrowed from the kiln owner – one of his arms was broken, rendering him unable to resume brick-making in order to repay the loan. “Why is every robbery that occurs in the radius of 10 kilometres [from Isa Nagar]blamed on us?” asks Mushtaq. Other residents of the village say that none of them has ever been proven to have committed a robbery, yet the police believe all of them to be thieves. Mushtaq feels the reason is their religious identity, which makes them socially vulnerable to bullying and persecution.

At a run-down police station near Gujjumata, a head constable does not want to explain why all robberies in the area are blamed on the residents of Isa Nagar. When his subordinate tries to come up with an explanation, he gets a stern look from his boss. Unable to remain silent, as soon as he moves away from the admonishing eyes of the head constable, the subordinate says, “Our bosses have to satisfy the landlords [zamindars]who have been robbed. We have to show them that we are doing something,” he says. “Keeping the Christians in lock-up shows the landlords that we are doing our job.”

Back at Isa Nagar, another problem has erupted. Twenty-year-old Raju who works at a nearby earthenware factory was arrested as soon as he got home. Raju’s father has come to Pastor Liaquat for advice. “They say he has an illegal gun, but we have never seen Raju with a gun,” laments his father. Liaquat offers them water and promises to help them as much as he can. “We will pray to the lord, this Sunday, to make these problems go away,” he tells Raju’s sobbing father.

Pakistani Christians gathered after the attacks in Lahore, 2013. Photo White Star

Pakistani Christians gathered after the attacks in Lahore, 2013. Photo White Star

There was no Joseph Colony in Lahore before 1978, when the authorities decided to relocate a small Christian settlement near Kashmiri Gate, one of the many entrances to the Walled City of Lahore. The Christian houses were seen as hampering certain development projects in the area and so the government offered the Christians a deal: if they vacated the settlement land immediately, they would get three marla (75 square yards) plots in Badami Bagh at a subsidised price of just 4,500 rupees [$45] and that too payable in monthly installments of 100 rupees [$1]. This is how Joseph Colony came about. When the government gave the Christians the land, they were also promised that they would not be displaced again, says Rosie Marshall, who bought a plot in the colony 35 years ago. Her husband Parvez Marshall is a PMLN worker and has served a stint as a member of the union council.

Their daughter-in-law, Saadia, is devastated by the attack on the colony. “Everyone regarded me as the luckiest girl in the world because I had two houses in the colony to call my own. The one I grew up in and the one I am married into,” she says. “Now I realise how unlucky I am. I lost my entire world in one day. They burnt down both my houses.”

When the 23-year-old saw television footage of her neighbourhood in flames, she could not wait to check if her house was also part of the wreckage. But the police wouldn’t allow Saadia and her family to re-enter the colony. They told her that the danger was not yet over. After fighting her way in, she almost wished she hadn’t. When she entered her bedroom she saw that the door of her locker had been flung open and all her wedding jewellery had been taken away. The furniture had been burnt to ashes. “I was holding the ashes of the furniture my parents had bought for my wedding when other members of my family walked in,” says Saadia.

In another part of the colony, Sheedan’s family has a similar story to tell. The government has been generous in providing financial help to the residents of the colony, giving 500,000 rupees [$5,000]each to all married male members belonging to each household. But what about educational degrees, official documents and family photographs that were burnt away in the fire, she asks. “No government can give me back my great grandfather’s pictures. No amount of money can buy back my trust in the police and political leaders,” Sheedan says.

Her young daughter Nancy is furious with those responsible for the fact that she is now living in a house with charred walls. She is also furious with the police for allowing this to take place. And, unlike most residents of the colony, she is determined to fight back if something untoward happens again. “This time we will not run away… We may be poor and we may be non-Muslims but we can bear only so much,” she says.

In another part of central Punjab, a tiny non-Muslim community in Doda village, near Sargodha, shows how resisting to pressures from the Muslims living around them is not always possible. At the time of Partition, a few Hindu and Sikh families in the village were stopped by their local Muslim friends from leaving for India but, since then, these families have only seen many of their members becoming Muslim. On a hot June day this year, a non-Muslim resident of Doda refuses to speak to a group of visiting journalists. One of the local Muslims present on the occasion claims that he is upset with his elderly father having converted to Islam earlier that very day and his mother is bringing the whole house down with her crying and wailing.

The other problem such small non-Muslim communities living in villages in Punjab face relates to the marriage of their children. Neither the Hindus nor the Sikhs are numerous enough in these areas to be able to marry off their younger generation within the followers of their own faith. “There are many limitations in the Hindu religion regarding marriage between cousins, so it is often difficult to find suitable matches,” says Ram Prakash, a teacher in Sargodha city. As a result, many Hindu families have formed marital relations with Sikh families. Prakash himself is a Sikh married to a Hindu woman. “Intermarriages between the two communities are no longer shocking nor are they rare,” he says.

It would be a sweeping statement to say that all of Pakistan’s non-Muslim citizens lead the same lives as the residents of Joseph Colony – marred by fear, persecution and discrimination. There are pockets in the country, albeit small, where religion does not play a defining role in social relationships. Balochistan’s Lasbela district is one such area where a sizeable Hindu population lives as peacefully as any community can in this part of Pakistan. “Maybe in Khuzdar and Kalat, things are bad for the Hindus but in Lasbela everything is fine,” says 19-year-old Kailash Turshan who is going to start his third year of an engineering degree this fall. To prove his point, he mentions how a number of Hindus run all kinds of businesses in Bela city – from grocery stores to vegetable shops to restaurants – and the Muslims have never had any problem in purchasing food from them. […]

Another region relatively safe for non-Muslims is Sindh’s Tharparkar district. The only complaints that one hears here are about occasional incidents of Hindu girls getting abducted and forcibly converted to Islam. “But look at the numbers of girls abducted in Thar,” says Dr Sono Kangharani, a member of the Pakistan Dalit Network, “and it is almost nothing in comparison to hundreds of abductions that take place in upper Sindh.” […]Kangharani says one reason why Tharparkar does not experience any religious violence is because it has almost as many non-Muslims as it has Muslims. In almost half of Tharparkar’s 22,000 villages, the Hindus own their own farmland, he says. In contrast, non-Muslims in upper parts of Sindh and entire Punjab are not privileged enough to own any land of their own.

Villagers in Tharparkar are surprised when asked if they get along well with people who do not profess the same religion as they do. Their immediate reaction is to question why they would not get along well with other human beings. Lakjee, an upper-caste Hindu who lives in a small village 30 kilometres from Mithi, says his parrah (traditional Tharri housing enclave) is surrounded by Muslim parrahs from all sides and they all live as brothers. “A long time ago, our forefathers wouldn’t eat with Muslims, but with the spread of education we have realised that the concept of untouchability is unnecessary,” he says.

The Muslims from the nearby Sangrasi Jotar village echo his views. Even though a Muslim maulvi comes to their village every now and then to preach that they should not share cooking and eating utensils with non-Muslims, according to a young boy, no one listens to him. “He comes, he preaches and goes back. And things stay just the way they are,” he says laughing. […]

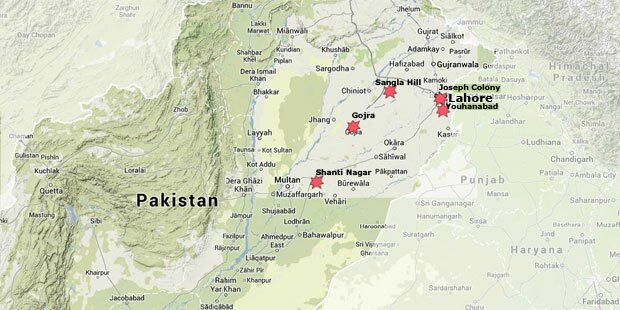

Sites of the incidents mentionned in this article.

Sites of the incidents mentionned in this article.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, there were scores of villages in Punjab where people belonging to the Chandala tribe embraced Christianity in droves. The Chandalas are one of the indigenous tribes of Punjab who were kept out of the Indo-Aryan caste system in order to force them under political, social and economic subjugation. According to John O Brien, the author of The Unconquered People, a book that traces the history of the Chandalas, their subjugation was the main reason behind their mass conversion to Christianity.

Between 1901 and 1914, almost 14,000 Chandalas stepped into the fold of Christianity. By 1947, this group had developed a new identity for themselves as Punjabi Christians. By then, they had also succeeded in concretising this identity through developments such as translating the English Psalms into versified Punjabi for communal singing and the addition of the appellation “Masih” after their names.

For one such Masih, by the name of Naeem, the attack on Joseph Colony proved that the subjugation of his people is not over, even though almost a hundred years have passed since their conversion to Christianity. That their political and social status remains as lowly as it ever was is manifested in the Punjab government’s reconstruction plans for their houses. The workers that come to fix their houses have applied plaster on the outer surface of the walls – which have been weakened, and even split, by the fire – and then, they painted them in bright colours, especially the facades of the houses, to make them seem brand new from the outside. Whenever Naeem tried to explain to the builders that plastering the weakened structures was not a sustainable solution, he would be told to stop creating a ruckus, otherwise they would not even carry out the plastering and the painting.

In the absence of proper reconstruction at the government’s expense, Naeem and many of his neighbours have started doing it with their own money. After paying for the construction material and defraying the labour costs, he says, he will have nothing left from the 500,000 rupees [$5,000] the government handed to him as compensation. Apart from the additional financial burden the reconstruction has put on his financial resources, it is also taking time and is forcing his family members to squeeze their daily lives into even tinier corners of their small houses, strewn with heaps of construction material. “Three months have passed since the mob attack but my house is still under construction,” Naeem tells the Herald in June.

Behind him, construction workers can be seen building the roof of his house.

Residents of Joseph Colony say their houses were set alight by a chemical they identify as phosphorous. No one has conducted any investigation, legal or scientific, to ascertain whether the chemical used is phosphorous or something else but the local Christians seem to be quite familiar with it. “This is the same chemical that was used in Gojra and Shanti Nagar as well as when a church in Mardan was torched earlier this year,” says Michael.

Before the reconstruction could even begin in Joseph Colony, the members of another Christian community living in Francisabad, a huge all-Christian settlement a few kilometres to the south of Gujranwala city, faced the dire prospects of a mob attack. On April 2, 2013, scores of Muslims from a nearby village of Naroki came rushing into Francisabad, accusing a local Christian boy of committing blasphemy. The real reason for their anger is said to be a dispute between a Christian boy and a Muslim boy, both sharing a ride on a motorcycle rickshaw, over what music the vehicle’s driver should play. Unlike in Joseph Colony, the mob encountered local Christians ready to retaliate. Some Christian boys fired shots in the air from the safety of their houses to scare off the Muslim attackers, says Romana Bashir, the director of Christian Study Centre, an inter-faith harmony group based in Islamabad. Media reports and other accounts from the area suggest that timely and effective response by the police was another factor that averted the possibility of a repeat of what had happened at Joseph Colony.

Why did the police act so effectively in Francisabad but only stand by in Joseph Colony? Did someone bribe the police in Lahore to stay as silent spectators; did someone exert any political influence for the same purpose? Iqtidar of King’s College speculates that the residents of Sheikhabad, who are mostly daily-wage workers, are neither rich nor powerful so they could not have bribed or influenced the police. The only people in the area with means and money to do that are the owners of the numerous warehouses around Joseph Colony. The might have wanted the local Christians to leave the colony so that they could expand their businesses there but there is no evidence to link them so directly with the attack, even when some local Muslim community leaders insist that the attackers mostly were the employees of the warehouses who mostly belonged to areas outside Lahore.

HRCP’s Yusuf, however, is convinced that the police’s motive in allowing the rioting to take place at Joseph Colony was religious rather than financial or political. “The sympathies of the police usually lie with the Muslims,” she says. “Over the years, prejudices against non-Muslims have deepened in the society and this is visible at all levels – from the media to the judiciary to the lower ranks of the police.” The allegations of blasphemy, in particular, arouse emotions very quickly, says Yusuf.

Bashir’s experience of working on peace and reconciliation between the Muslims and the Christians in Pakistan seems to endorse this point of view. She tells the story of a man who was a member of the mob that attacked Shanti Nagar. During a reconciliation session, years later, he narrated how he ran from his village for a good 20 kilometres to reach and attack Shanti Nagar after a local maulvi announced that a Christian had insulted the Prophet of Islam. The police officials in Lahore could very well have felt the same way after hearing that Saawan Masih had committed blasphemy.

The traumatic impact of their failure to protect Joseph Colony is still being felt many months after the attack. Sixteen-year-old Sumya, whose father Mansha Masih runs a paan stall, is so traumatised that she cannot sleep in her Joseph Colony house any longer. Fearing that the mob can return, she leaves the colony every evening to sleep at her uncle’s house near Jail Road. “After seeing what we saw, anyone could lose their mind,” says Sumya. “I wish we, too, were burnt down in the fire. That would have been easier than what we are going through now.”

Maham Javaid

05 Sep 2013