In 1968, a half-dozen tourists check into a hotel in downtown Hebron: they never leave. Rue 89‘s reporter visits this city of 200,000 Palestinians in the West Bank, where a few hundred unwanted American guests now occupy the downtown, endlessly repeating that “Hebron is a Jewish city,” a place where the surreal is the everyday.

Imagine this: one fine day, a rich investor knocks on your door, all smiles, and offers to buy your house. For how much? A million dollars for the land and the building. Back of the envelope, that’s about a dozen times what your property is worth on the market. Agreed then?

You decline the offer, and politely but firmly usher the visitor out. Disconcerted by your unexpected refusal, the investor leaves, troubled. But soon enough, he is back again, with much more convincing arguments.

“Seize the chance to make a really good deal, my friend. Would ten million make you change your mind?”

“No.”

But the apparently extremely rich investor is determined. He is a hardened businessman who has overcome adversaries much tougher than bumpkins like you, with your insignificant dump of a house in this miserable neighborhood.

With the energetic and condescending tone of a vacuum cleaner salesman, he says:

“Twenty million? That’s at least 200 times what your shack is worth. Take it or leave it, my man. Don’t be pigheaded.”

“Out of the question.”

“Alright then… if you aren’t completely insane, surely you wouldn’t spit on 50 million. In cash, dude. With that kind of loot, you could reign like a phoenix among the Gulf petro-monarchies. The sheikhs will be making eyes at you, sidling up to try to marry off their daughters to your sons. Think about it. If I were you, my friend, I’d turn it over in my mind a few times before… ”

“Are you finished yet? You are annoying me. My house is not for sale. Beat it.”

Reflexively jamming his foot in the door, the investor, now really in a state, just succeeds in keeping it open. A nervous tic starts contracting the muscles of his face; an angry vein pulses beneath the skin at a damp temple. His hair, gray and sparse, bristles around his skull.

“I get it. You weren’t born yesterday, eh? Well here is my final offer. You are a real piece of work, Abu Hamed, but you are not crazy, or stupid. A partner of your caliber deserves a hundred million American dollars. Last chance. Sign the bill of sale: here, here and here.”

“La, La and La [‘No’ in Arabic]. Goodbye, Mr. Gutnick.”

And that is how, after weeks of an entirely surreal power struggle, you have turned down cold an offer of one hundred million dollars to sell your little house, a place that is at best worth a thousand times less than that.

At the same time, you have disgusted an impressively obstinate foreign billionaire, one who was prepared to shower you with silver if you would just cede him your humble dwelling and get the hell out. An improbable story?

Not so, dear readers. For the good people of Hebron, in the West Bank, the absurd has become the day’s drudgery, ten times over. Such insane bidding wars, crazier than the fierce bargaining that takes place in any Oriental bazaar worthy of the name (except that in a bazaar prices are usually bargained down rather than up), have really taken place.

And in truth they are merely amusing anecdotes among the hundreds of bizarre events-usually much less funny-that pepper the lives of residents of the biggest city in the West Bank.

The protagonists in this abortive real estate transaction-Australian billionaire Joseph Gutnick, financer of Jewish expansion in occupied Palestine, and Abu Hamed, humble Palestinian family man and owner of the much-coveted family house-are representatives of the two opposing camps, who every day regard one another in sullen silence.

They keep away from each other as much as they can. Tolerate each other only at the barrel of a gun. Size each other up in the silent hostility that they have learned to live with as the years passed.

Welcome to Hebron: population 200,000 Arab Palestinians, and 500 ultra-fundamentalist Jews, most of them American. And around 2,000 Israeli Army soldiers, armed to the teeth, and permanently stationed in key areas of the historic downtown to protect the Jewish inhabitants.

This region suffers from no lack of history; it has watched to flowering of the most ancient cities in the world, and, to its misfortune, the principal monotheist religions of the globe. The city of Hebron merrily displays its 4,000 years of existence and uncountable atrocities of all kinds; pardon me if I don’t go into the details.

The first ‘event’ – perhaps it would be better to say myth, but we won’t go there-which still has crucial importance in our era, took place in the 11th century B.C., which is to say about 40 centuries ago.

At that time, according to a rather tenacious legend, a Mesopotamian immigrant called Abraham bought from a Canaanite a field and a cave in which to bury Sarah, his wife who had recently passed away at the age of 127.

At the end of the tale, Abraham is buried in there as well. Later his son Isaac, his grandson Jacob and their wives Rebecca and Lea will follow. If you didn’t yawn too much during your catechism or your Quranic instruction or your Yeshiva classes, you have assuredly recognized some big kahuna biblical characters here.

You can definitely see why this celebrity cemetery, henceforth known as the ‘Tomb of the Patriarchs,’ is, due to its high concentration of VIP tombs, one of the most sacred places around for the Muslim and Jewish religions.

Over the thousands of years that followed, various places of worship were built, all worthy of this site’s reputation. Successively:

*A gigantic Jewish temple built under the reign of King Herod, which forms the base of the current edifice.

*A Byzantine [Christian] basilica, which Persian conquerors eventually razed to the ground in 600 AD, while sparing Herod’s sanctuary.

*And finally a mosque which Muslim conquerors started building in the year 640, enlarging and rearranging it several times.

Since then-and depending on the level of religious tolerance of the city’s masters-Jews, Muslims and even some Christians have made the pilgrimage, coming here in large numbers to pray in this important sanctuary. The Cave of the Patriarchs is in fact the second-most sacred sanctuary of Judaism after the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. However, Hebron is no longer a Jewish city, and has not been for a very long time.

In 150 AD, the Romans expelled and exiled the last Israelites who lived here, and afterwards the Byzantines formally forbid Jews from returning to Hebron or living in it.

During the period of Muslim domination, starting in the 7th century, these bans were abolished. Gradually over the centuries, a small Jewish community prospered in Hebron, though it always remained tiny compared to the general population, which was Arabized and became Muslim.

Except for a few isolated incidents the two communities lived peacefully side by side for centuries. The balance was brutally upset in 1929, when in a context of high Jewish-Arab tension throughout British Mandate Palestine, violent anti-Jewish riots broke out in Hebron.

Numerous houses and synagogues were ransacked, and 67 men, women and children were savagely massacred by the Arab population; around 15 percent of the city’s Jewish population.

Though hundreds of Hebron’s Jewish inhabitants had their lives saved thanks to Arab friends and neighbors who hid them or protected them, life side-by-side had been irretrievably lost, and all of those who survived quickly fled or were evacuated. Three years after the pogrom, there was not one Jew left in Hebron; it was the end of a little Sephardic community that had lasted one thousand years.

All of which brings us to the present situation, in which the normal and the absurd are one and the same. In the spring of the year 1968, immediately after the Six-Day War and the beginning of the occupation of the West Bank by Israel, a group of Israelis posing as Swiss tourists, led by a fanatical rabbi, booked rooms in a hotel in Hebron’s historic downtown.

Once settled in, the “tourists” revealed their true identities and announced that they had absolutely no intention of leaving. After a few years of political wavering, and some Palestinian terror attacks, the Israeli government ended up legalizing the Jewish colonization of Hebron’s historic downtown.

And so, thanks to state and army logistical support, and the immigration of politically fanatical ultra-orthodox New York Jews, and the financial support of zealot organizations based in Israel and overseas, the colony was able to grow, slowly but surely. And in all cases to the detriment of the Palestinian population. Nowadays, the result is impressive.

Only thirty kilometers from Jerusalem, Hebron is another world entirely. When I visit it with the Green Olive Tours organization, accompanied by three tourist women, two from Germany and one from Iceland, we are obliged to change vehicles in Bethlehem, where we finally meet our guide, Ammar, 30.

Ammar would definitely have liked to come and pick us up in Jerusalem, but like all Palestinians under 50, he has been banned from visiting Jerusalem for a good dozen years now, though he lives only 10 kilometers away. That’s how it is, what can you do.

So, a change of guide and also a change of car, for one with Palestinian plates that lets us fit into the local landscape, and off we go toward Hebron.

The wind blows furiously through the hills, planted with olive trees, that range along the road; rain pours down in violent torrents along our route, to the great joy of Ammar, who warns us, laughing, that he has never driven a car in such conditions.

“The drought has been plaguing us for years. Maybe we will suffer less from a lack of water this year, insha’allah,” he says.

My lord, this is the wettest drought I have ever seen. The road we are taking is, it seems, one of the last that allows access to Hebron, the others having been closed by the army.

We pass through checkpoints, Palestinian farms, Jewish settlements on the tops of the hills, with militarized bus stops that serve them. But most of all, vineyards and olive orchards that green the rocky land as far as the eye can see. Even under this heavy rain, the landscape is magnificent.

Soldiers are everywhere. With their khaki fatigues, in this weather, we can only make out their green silhouettes and their impressive rifles. Vineyards, olive trees, khaki fatigues: the local floral triptych of the pastoral valleys of occupied Judea (disputed territory, in the terminology of the other side).

We are, according to our guide, on one of the ‘shared’ roads, open to all, Palestinians and Israelis alike. He directs our attention to the signs in Arabic and Hebrew that proclaim to drivers that these shared roads ‘promote coexistence and peace.’

Our ignorance of the languages the sign is written in oblige us to take his word for it. He goes on:

“During the second Intifada, this was the most dangerous road in all of Palestine. It was not uncommon to be suddenly slaughtered by automatic rifle fire from a car coming down the opposite lane.”

We think about these grave words, and consider everyday life when you are afraid of being machine-gunned by every car that drives by yours, as we turn at an intersection and Ammar pauses briefly to let us read this sign:

Entrance by Israelis is forbidden, dangerous and against Israeli Law. Photo Lecteur X, Rue 89

Entrance by Israelis is forbidden, dangerous and against Israeli Law. Photo Lecteur X, Rue 89

This road leads to area A under the Palestinian Authority. The entrance for Israeli citizens is forbidden, dangerous to your lives, and is against the Israeli Law.

What mad world is this, in which, depending on whether you are Israeli or Palestinian, you are not allowed to go to this or that place, while citizens of any other country can come and go as they please? That’s how it is, what can you do.

Having said that, I later learn that it is not actually “Israeli Law” which forbids Israelis from venturing into Zone A, but the army. A subtle distinction, I will concede, but a real one, and legally significant.

Upon our arrival in Hebron, Ammar parks the car in a lot, and points out the green painted windows on the houses nearby, with little ladders underneath them.

We probably would not have paid the slightest attention to these discrete adjustments, superficially so benign, if our guide had not explained that the people who live in these houses are prohibited from using their own doorways, sealed up by the Israeli army for the “safety” of the settler fanatics.

So to get in and out of their houses, they have to be inventive: make some holes in the back wall, widen some windows, or worst-case scenario, the house’s roof can be turned into a hatch. That’s how it is, what can you do.

With doors welded shut, windows become entrances.Photo Lecteur X, Rue 89.

We continue on toward the historic part of town, downhill a bit. Narrow streets separate the ancient stone houses, Ottoman architecture, an omnipresent style in Israel and Palestine, a style I soon grow accustomed to.

The souk is a rather sad place. Not many merchants, most of the shops closed behind their locked heavy iron gates. Economic activity in old Hebron is afflicted by the nuisances of the settlers, the presence of the army.

A desolate downtown, replete with settler graffiti and imprecations.

Hebroners prefer to live and work in the H1 zone of the city, the one that is still entirely under the effective control of Palestinians, far from the accursed settlers, soldiers and road blocks of Zone H2.

Emerging from the indoor galleries of the shops, and finding ourselves on the pedestrian streets, we note a metal grillwork above our heads, intensify the oppressive feeling that oozes from these streets, deserted and silent at 10 o’clock in the morning.

The grill astutely separates the street below, with its Palestinian inhabitants, from the houses overlooking it, where the settlers live.

The Palestinians themselves ended up installing this hideous barrier so they could stop worrying about being hit in the head by projectiles or garbage as they wandered through the souk. I will leave it to you to imagine the origin of the undesirable projectiles we are talking about.

A steel grille to protect the heads of Palestinian passersby.

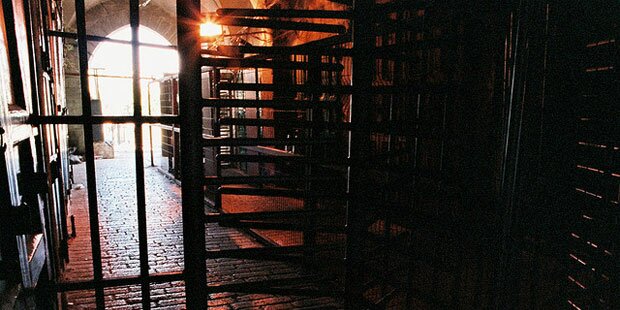

After this short turn through the old city’s moribund souk, we get to a galleria and inside it, a first checkpoint: armed soldiers, iron fences, metal revolving door, metal detectors: the whole nine yards.

Past the checkpoint rises the angular and imposing silhouette of the Mosque of Abraham. We follow Ammar, who takes us to the entrance marked “for Muslims only.”

“But Ammar, we are not Muslims, can we still go in there?”

“Of course you can, you aren’t Jewish. That is was counts.”

Another checkpoint, just for the hell of it, though this one without the revolving door, and here we are, inside the actual ‘mosque.’ Ammar explains that previously, Jews and Muslims prayed side by side in the same building. But after the 1994 massacre, carried out in the middle of Friday prayers, by Baruch Goldstein, an extremist American settler, the sanctuary has been strictly divided in two.

Half is Jewish, and half Muslim, and between the two no physical contact is possible. Each jealously guards his half and forbids the other access to it. Foreigners, on the other hand, be they Christians, atheists, Beelzebub worshippers or Pastafarians, can do as they please and go where they want. Nothing more normal than that. This is called living together.

Furthermore, ten days out of the year, during their important religious celebrations, the Jews use the entire building, prohibiting access by the Muslims. The compromise seems to work reasonably well.

But when you talk about “The Mosque of Abraham,” you are talking about Abraham, and when you talk about “The Tomb of the Patriarchs,” you are talking about a tomb. In the center of the sanctuary, sealed away in a little room that is off limits to mere mortals, stands an impressive monument draped in green velvet and ancient dust: the tomb of the venerable Abraham himself.

How many times do I have to tell you this? Well, here it is again: A pilgrim here communes with himself, calls on the spirit of the patriarch, all while leaning against…an internal window. The small room with the cenotaph opens onto a window for the Muslims, on the mosque side, and a window for the Jews, on the synagogue side.

This is the only place in the building where the two halves to the sanctuary might communicate, at least if it weren’t for the bulletproof glass that separates the tomb room in two. This solution, which it must be said falls short of the divine, aesthetically speaking, does give the faithful a sense of relative security. Just in case the crazy guys from the other side bring in a rifle or a grenade. That’s how it is, what can you do.

Abraham’s Checkpoint.

A few more visits and some further explanations and we leave the mosque. We head down the gently sloping esplanade until we get to the lower street. Here, Ammar tells us how to reach the entrance to the Jewish side of the sanctuary. He, as a Muslim, is not allowed to get any closer. He will go and drink tea at the shop in front.

We agree to meet him afterwards here for lunch with the owners of the shop. And so off I go, accompanied by Icelandic and German tourists, up the side of the esplanade ‘reserved for Jews.’ A first checkpoint, then another, and here we are inside.

But not for long; without our guide to explain the important details, the visit is less interesting for the starving tourists, wet and shivering in the cold. We can’t wait to get back to meet up with Ammar and sit down for something to eat with a Palestinian family.

Our rendezvous point is easy enough to find: leaving the synagogue, we head down the steps until we reach the street, and right there in front of the checkpoint and the Gutnick Center, we meet our guide and a few members of the Palestinian family with whom we’re having lunch.

Other than the checkpoint, incidentally, the street is deserted. A low wall divides the street into two very unequal parts:

*To the left, the wider side is reserved for the Jews, who may walk or drive their vehicles on it.

*The narrow side is reserved for the Muslims, who may only walk, and are obliged to turn to the right before the checkpoint as they head toward the Mosque of Abraham or the souk.

Past the checkpoint, the rest of Shuhada Street, Martyrs’ Street, once an important commercial artery in Hebron’s historic downtown, is forbidden to Muslims. Aberration? Apartheid? That’s how it is, what can you do.

The street, henceforth reserved entirely for Jews, passes in front of the Gutnick center and continues toward the outskirts of the city, where it serves the radical orthodox Jewish settlement of Kiryat Arba, population 7,000. The same settlement the fanatical murderer Baruch Goldstein called home, and where he is still venerated as a ‘hero.’

Arabs to the Right, Jews to the Left. Photo LecteurX, Rue 89.

We are to have lunch at the house of a man who introduces himself as Abu Hamed, one of the last Arabs of Martyrs’ Street. All the others have seen their shops go to ruin, their houses seized. In the least bad cases, their doors have been “simply” welded shut with blowtorches and soldering irons and they have been obliged to leave.

For reasons that escape me, the army has not yet found a way to do the same to Abu Hamed and his family; so while they still can, they cling desperately to their house. Literally.

In point of fact, they can never leave the house for any reason whatsoever. From what we are told, if by chance they ever were to leave it empty, even for a few hours, upon their return they would assuredly find it being squatted by settlers under the protection of the army, and the bout would be permanently lost.

To avoid an outcome like that, Abu Hamed’s family must make sure that there is always someone in the house. Life in Hebron is like that; what can you do.

Financially, the situation for the Abu Hamed family is anything but prosperous. Arab clients are extremely rare, since the family shop, on the ground floor of the house, is located on the portion of Shuhada Street that is entirely inaccessible to Palestinians.

Except those few the Israeli checkpoint permits to pass: the inhabitants of the house and a few rare and known faces, like our guide. To get by, they depend almost exclusively on foreign tourists who come to buy a few souvenirs and locally-made knickknacks.

They make ends meet by cooking food for foreign visitors who pay 35 shekels-about seven Euros-to have lunch in their living room and converse with them. A good meal, simple, healthy and extremely copious.

Abu Hamed and his eldest son are entertaining hosts. Perhaps too entertaining though; instead of answering my pressing questions about the horrors of everyday life in Hebron, they prefer to joke with us and flirt with the blue-eyed foreign girls. They will perhaps tell us about their miseries another time, when there are fewer beautiful blondes in their living room to impress.

Certainly Abu Hamed’s financial situation would improve radically were he to accept the vertigo-inducing offer from Joseph Gutnick. I can now brag that I have had lunch in a hundred-million dollar home, dear friends! It is barely credible.

But for Abu Hamed, the offer is simply out of the question. Joseph Gutnick is Jewish, and a self-respecting Palestinian man does not sell his land or his house to Jews. It is as simple as that. Even if the penalty you must pay is house arrest in perpetuity, living in front of an extremist ‘cultural center’ that plays head-poundingly loud music all the day long.

A Palestinian who dares to transgress this taboo is a traitor, and avoiding such infamy is more than enough reason to definitively snub Joseph Gutnick’s multimillion dollar courtship.

The Arabs affectionately call Abu Hamed “Sumud”, ‘The Inflexible,’ ‘The Steadfast’, ‘The Determined,’ while the Jews saddle him with the rather less complementary sobriquet ‘Majnun,’ ‘The Loony.’ Exhausted by the unlikely litany of absurdities, I finally ask him:

“But why do they want so badly to drive you out?”

“Simply because for them, ‘Hebron is a Jewish city,'” [in English]he says. “They want to live among Jews only, here. They want to drive out all of the Palestinians, to the last man. And the army systematically lines up on their side.”

“Alright, so they want you all to go. Which means, if I understand correctly, is that all they need to do is expel about 200,000 people.”

“Exactly, that is, in the end, their plan.”

The visitors from New York would like some more.

Lunch over, the guests are stuffed, but Abu Hamed begs Ammar to stay a few more minutes so we can all take tea together. Leaving the house of one’s host without taking tea would be seen as extremely impolite.

Our guide can only accept, in order not to offend the inflexible patriarch of Martyrs’ Street. After which we say goodbye to this warm family of Immovables, condemned to remain prisoner in their Palestinian Hotel California for an indefinite period.

The cheerful goodbyes of Abu Hamed, sheltering from the pouring rain under his porch, beneath the (I suppose) indifferent gaze of the soldiers in their balaclavas, have something poignant to them, pathetic and absurd. Something so Hebron.

But what a jinx, this bad weather. Our guide Ammar informs us that we won’t be meeting with any American colonists. When tours go well, the tourists have a chance to talk to them.

Ammar even personally knows one colonist, a young American from Brooklyn. They have a nearly cordial relationship, and they sometimes happen to exchange nearly friendly words. One time, the settlers actually invited the tourists into their house.

But Ammar could not follow his group of tourist to the house of the Jews: the soldiers would never have allowed it, not even in the company of a dozen Westerners, not even at the express invitation of the settlers. Orders are orders: no Palestinian ‘terrorists’ among the Jews.

That’s how it is, what can you do? So, in solidarity with their guide, the group of tourists had decided to decline the rare invitation. No such luck for us today in any case: not a single settler to get our hands on.

It is cold outside, and raining buckets, coming down hard enough to flatten the hump of a camel. Nobody is in the mood to wander the street and chat with the tourists, not even to peremptorily say that ‘Hebron is a Jewish city’ [in English]. Everyone is staying warm inside.

The besieged ‘Obstinate’ of Shuhada Street had told us, in all seriousness, that the weather forecast is warning of snow in the next couple of days, possibly quite a bit of snow. Snow in Palestine, in Judea, in Hebron, in Jerusalem; what a comedian, our Abu Hamed!

We finish our visit to Hebron in Zone H1, under Palestinian sovereignty. Hebron is famous for its ceramic and glass work; so Ammar takes us to visit the glass-blowing workshop of the Natsheh family.

The dexterity of the workers is impressive, the workmanship of their crafts impeccable. But what I find myself appreciating above all is the heat of the ovens, where I shamelessly sidle up to warm myself, wondering all the while how this could possibly be bearable in the inferno heat of the summers here.

The girls can’t resist buying some decorative objects on sale at factory prices. But the idea of putting any more weight in my luggage, filling them up with fragile glass knickknacks, dissuades me from doing the same.

Though this part of the day’s program is less ‘exciting’ than what came before, it is comforting to see that parts of life in Hebron are more or less normal, that everyday life for all of this city’s 200,000 people is not just a succession of humiliations, streets divided by walls, doors welded shut, and checkpoints.

In Hebron, the vast majority of people live in Zone H1, and ‘only’ 30,000 unfortunates have the bad luck to live too close to the Tomb of the Patriarchs and the zealous settlers. That’s how it is, what can you do.

One final turnstile.

It is time to go. Our guide Ammar brings us back to our car; I think to myself that perhaps at this point a boat would be a more advisable way to continue our journey. We are far from finishing the day’s ambitious program: we still have to see Bethlehem, its churches, its ten meter high security walls, its Banksy graffiti, its refugee camps.

I leave Hebron thinking vaguely that during the exit interrogation at Ben Gurion airport, I would be better off not mentioning my visit to Hebron.

Jean-Michel Hauteville Translated from French by International Boulevard

25 Jun 2014