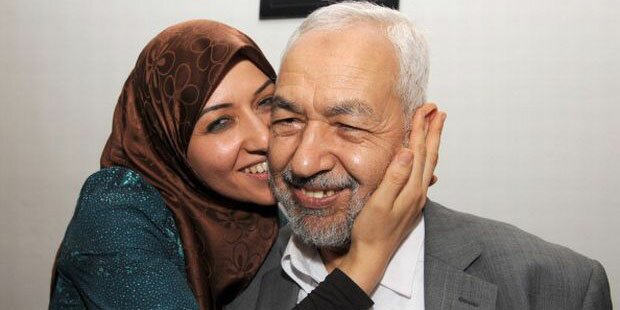

While the grim farce of Egypt’s military-dictated constitutional referendum comes to its violent end, a more fortunate process is playing out in Tunisia. The majority Ennahda Islamist party, willing to give ground and surrender power to avoid a political crisis, seems to have shepherded a democratic and consensual constitution through the country’s constituent assembly, despite the violent opposition of far-right Salafi Islamist groups. In Le Monde, an interview with the party’s longtime leader Rached Ghannouchi:

Three years after the fall of the former regime, Ennahda decided to quit the government. How did you explain this choice to your own party activists?

We told them: ‘you are leaving the government, but you have not been defeated, you are leaving with your heads held high. Why would you want to remain in a house that is collapsing on you?’ There was indeed a serious danger because our presence in the government was an obstacle to the drafting of the Constitution, since the opposition was boycotting the Constituent Assembly. We could not have written a Constitution alone. Or if we had, we would have done it with the two thirds of the votes. But we would have driven ourselves into a situation like the one in Egypt, with a society divided between [Islamist] supporters and supporters of secularism. We did not want this result. We had to chose between staying in government or the success of the Tunisian democratization process.

Our decision to leave power was our own choice, based on an ethical decision. On February 5 we had signed a roadmap agreement that planned this path; it was not an easy thing to attain. I have taken the responsibility for this decision with several other leaders of Ennahda. We did not lose the elections, we were making a sacrifice in the interest of the country, for the success of the democratic process. In Tunisia today, there is a strong sense of relief; we are part of this country and we share this feeling of relief.

So what happened in Egypt was therefore crucial?

Yes of course; what happened in Egypt was an earthquake. It made the opposition here ramp up their demands and contemplate an “Egyptian scenario.” But the Tunisian people did not follow along. Tens of thousands of them protested against the political assassinations, but they refused to become a pretext for a coup. They showed their rejection of the assassinations [of prominent political figures from the Tunisian left]but they did not allow these assassinations to become a political alibi for chaos.

How do you see the role of Ennahda now? As an opposition party?

We cannot really speak of opposition and governing parties anymore. This is a totally new situation, with a government of political consensus, that is neutral, in charge of leading the country toward the next elections. This government will have all the powers of a real government, and it is being supported both by those who were until recently in power, and by the opposition. It is not representing either side.

After two years exercising power, what are the political failures you are willing to acknowledge having made?

The [democratic]transition lasted for too long. All the problems actually began in the second year because it was just taking too long, even though it was not of course meant to take all that time. We had made the mistake of thinking we could get everything done in only one year. But the Assembly was busy with more than drafting the new Constitution; it also had as a mission like any other parliament in the world of setting policy for the government, passing laws, signing international conventions. Maybe we should have let the Assembly solely focus on the Constitution while the government managed the country through decrees.

When we came to power the country had a negative growth, with -2 percent, while today it is positive at 3,5 percent. The money that was set aside for development has still not all been used, sometimes only up to 20 to 30 percent of it was actually used, and this is the reason we still have protests and rioting in certain regions of the country.

We should have behaved in a more revolutionary way in reforming the bureaucracy that we inherited from the previous regime, especially in the way the process for bidding out government contracts works.

You are also accused of having been complacent with the Salafis.

There has been a real improvement in the security situation over the last six months. But perhaps we should have been more firm from the very beginning. Our experience in government is still too fresh, we are learning everyday. At the beginning those extremists were not committing any violence, so we tried to have a dialogue with them, in order to have them join a legal framework, which worked with two of the Salafi parties. But others chose violence, and our government labelled them as terrorist organizations.

The Constitution that is being voted now grants religious freedom and freedom of belief; it also grants equality between men and women… Is Ennahda the antithesis of the Egyptian Muslim Brothers?

Every country has its own peculiar experience. We have exported the peaceful revolution but we do not want to import the Egyptian violent counter-revolution. And we are proud of this Constitution, which brings together a moderate vision of Islam and universal values. It reflects the coalition that we have formed between Ennahda, a moderate Islamic party, the CPR and Ettakatol, two moderate secular parties. This is the Tunisian Way.

We came to the conclusion that adding to this constitution references to the Sharia was not helpful because the word Sharia is not clear for certain people, and a constitution needs to have only what is clear and common to all. We do not want a divisive text, and we want Muslims to live a country that is open on the world. This has been the ambition of Tunisian reformist Islamists since the 19th century. If concessions are needed to achieve this we are ready to make those concessions, as we did when we decided to quit the government.

Some of the provisions you are mentioning were voted by a large majority, some even unanimously. A few issues remain that are now being examined by the deputies in regards to separation of powers; we are trying to reach a balance between a presidential and a parliamentary system. We think that the more that powers are separated, the better. We do not want to end up with a strongly centralized system that will bring us back to the era of despotism–neither a despotism of Ennahda nor anyone else.

Wasn’t the opposition a key in those achievements?

The opposition participated in a national dialogue that could have never succeeded without its presence. In the beginning the opposition was demanding the fall of the government and the dissolution of the Assembly. Eventually each side made concessions. Our advantage is that we had a tangible tool in our hands, the government, while the opposition conceded where it was in the minority, in the Assembly.

Forced to leave power, Ennahda has succeeded in flipping the situation to its own advantage. But how are you planning for the next elections where you still need to win over a disappointed electorate?

There is no magic here. People are attached to ethical values, want a calmer political environment, and they detest this unremitting battle for the power. They will have points of comparison, and will understand that the country is facing structural problems. For us, we are happy to have been able to preserve the state and public services, and most of all the freedom. We have put the country on the rails toward democracy. We have an electoral committee, a Constitution that is almost finished, independent media, a anti-torture committee and a transitional justice one. We have translated into institutions the first values of our revolution. We want to see the next presidential and legislative elections happening between the months of June and August 2014. The more the elections deadline is delayed the more the situation will become risky. This is the lesson we drew from our own experience: transition periods need to be as short as possible.

Have you had to face obstacles from Arab regional powers among the Gulf countries, as Tunisian president Moncef Marzouki has claimed?

It is probable that a number of Arab countries are unhappy with what is happening in Tunisia because they fear democratic contamination, but we do want to have excellent relations with all Arab countries. We are well aware of the fact that we are a tiny country and we know our limits.

Isabelle Mandraud Translated from French by International Boulevard

16 Jan 2014