At the edge of the phantom city of Chuquicamata, the Codelco copper mine yawns like a hellish mouth three miles wide and 1,700 feet deep. Six years ago, the mining company had run out of room to dump the mine detritus, and decided that it was cheaper to move all 18,000 people out of this Chilean city than to keep trucking the debris away. From Etiqueta Verde, a walk through the ghostly ruins and the memories of the city’s exiled inhabitants.

On Christmas Eve in 2007, Alcides Lira appeared at the door of his home for the last time. For days, he had spent the mornings packing boxes to leave — he packed pants and shirts, a toothbrush, razors, and family photos — and then in the evenings he had again unpacked them to stay.

That Christmas in Chuquicamata, three hours from the border between Chile and Bolivia, Alcides Lira’s house was the only one with lights on in the mining camp. A camp, by definition, is ephemeral: something installed today to be picked up tomorrow, or the following week, or any old day. Alcides Lira — 80 years old, thick mustache, white hair — had lived in the same camp for 70 years. With time, Chuquicamata had turned into a town with streets, schools and cement homes. A town, by definition, is permanent: something built to stand and endure. But a big move had started three years ago when the 18,000 inhabitants were obligated to move to Calama, a city 15 kilometers away. The copper mine that had brought them there was now kicking them out. Soon, it would start dumping the mine waste on these homes. The night Alcides Lira abandoned his home, Chuquicamata was about to be buried under rock.

Chuquicamata, the camp that today looks like a ghost town, remained for 90 years in the Atacama desert next to the copper mine that built it: a crater five kilometers across, three kilometers wide and almost a kilometer and a half deep, all sculpted with the sophistication of an amphitheater. New York’s Central Park would fit in it, and three Empire State Buildings, one on top of the other, could stand up in it and there would still be space. It is an infinite pit generating $8000 a minute. The owner of this hole spitting money is the National Corporation of Copper (Codelco), the largest state-run company in the history of Chile. President Salvador Allende nationalized the metal in 1971, and since then Codelco has been in charge of administering Chuquicamata. But this mine with a quechua name was created with an English accent. In 1912, the Guggenheim brothers bought mining rights from the Chilean government. They had on their hands the challenge of transforming this ferocious land: an expanse of sand and rock at 2870 meters [nearly 10,000 feet]above sea level, with 100-kilometer per hour winds (just below a hurricane speeds) and the most extreme of ultraviolet rays, according to international studies. Besides, it was the driest area in the world. Up here, where the sun burned and nothing grew, only ambition made it possible to live for 100 years. At first, it was just a handful of miners and their families. But the camp grew and businessmen started to arrive, opening up grocery stores, small stands, and markets. At one time, Chuquicamata had 20,000 inhabitants, among them miners and their families, businessmen and service personnel: doctors, teachers, firemen. Far from everything, close to the sun. Nothingness and copper.

.

.

When men and their machines arrived to the desert, the only town close by was Calama, a few miserable homes built into the emptiness like a way station. A mine demands a universe around the quarry, a place to wash up and sleep. Because of that, the Guggenheims had to provide the infrastructure, and a way to make people want to live in the middle of the desert. If someone had said it, the words might have been these: ‘You are going to have a house. You aren’t going to pay for water. You aren’t going to pay for electricity. You are not going to pay for gas. We will give you everything: medical attention, education for your children, food and entertainment. You will come work and get your salary, and on top of that, you will live for free’. They assembled a microcosm of the outside world where nothing was missing. Wide and impeccable avenues were built. A security system was installed and a community was forged around a common bond: a job and life after that job in which everyone participated.

But Chuquicamata’s evolution was incapable of adapting to the environmental norms that arose. The foundry was installed, and it emitted carbon dioxide and arsenic, vapors incompatible with life. The mine, besides, started to devour the space taken up by the camp. A kilogram of copper required the extraction of 100 kilograms of useless rock that had to go somewhere. It could have been anywhere: in the desert there’s an excess of space. But in one day mining trucks use the same amount of gas a car uses in two years. This is very expensive transportation for a bunch of unusable rock and sand. They started to throw the rocks around Chuquicamata’s periphery, cornering the homes. Little by little, this turned into an impassable wall of waste, one that would soon reach the town. In practice, that meant burying the city or building another one. Cities are not chess pieces. At some point, in some place, perhaps sitting with a map, someone had to say: ‘Gentlemen, we have to move this city from point A to point B, but where do we start?

II

Sergio Jarpa is a mining engineer capable of picking up a town and moving it, an entire town with its streets and houses, its stores and schools, and also its people. The residents of Chuquicamata — the then-vice president of Codelco Norte remembers — weren’t going to pull up stakes on their own: “It’s easy to get used to something. The difficult thing is to move 18,000 people, who are used to getting everything for free, and make them into normal Chilean citizens.”

For Sergio Jarpa it was an experience of going door to door, giving bad news: you have to leave your home, your town, your life. The inhabitants of Chuquicamata didn’t just work together, they had married and formed families. Nothing belonged to them in that camp, but it all felt like theirs. In Calama, on the other hand, they would own their homes. Codelco saw to the construction of 5,000 homes — one for each family — and assumed 50 percent of their financial compensation. They built streets, squares and sidewalks, a new hospital, new schools. They moved the businessmen, the doctors and teachers, the police and firemen, the priest and the church. Jarpa, the man in charge of moving everyone, marked the final day on his calendar. It was going to take three years. The time would come for each of the inhabitants. Starting in 2004, each one would get their turn to leave their home. On an average, four families left each day. In a month, a neighborhood could disappear, and in a year 1,500 families. But they all said goodbye on the same day: September 1, 2007 was the day of commemoration, the official closure. Noon was the agreed upon time to say goodbye. Residents and authorities crowded the camp. There were speeches and a commemorative plaque. There was an orchestra, live bands and fireworks. 30,000 chuquicamatinos had arrived from all over Chile and outside the country for the final event. Everyone felt the same: as if they were holding a wake. That day, Chuquicamata officially died. But they still had to bury it.

III

When the moving truck arrived, Miria Hernandez — 78 years old, fifty of those years in Chuquicamata — was eating breakfast. She had known the day they would come for her, but not the time. That was why she had to have her things ready the day before. And that morning, as she was eating breakfast — maybe cup of tea and bread, the town’s typical breakfast — the sound of the truck ruined her appetite. She wasn’t expecting them so early. Minutes later, like Christ in procession, she and her daughter followed the moving truck in their own car in a silent Via Crucis toward Calama. It was last stage in the long harakiri of putting their lives in cardboard boxes: their last day. It all happened quickly: the truck, the loading, the handing over of the keys, the departure. At that age, one does not even imagine having to live in a different place.

“I still can’t get myself to like Calama,” says Miria Hernandez. “I set up the house the same as in Chuqui, everything in the same position, but I still miss living there.”

When she sleeps, she still dreams of Chuquicamata. Sometimes dreams insist on showing up time and time again. And the dream of living in Chuquicamata had started to end in 2004.

Miria Hernandez’s ritual repeated itself every day, as it did for the rest of the inhabitants over three years. Codelco covered the doors and windows. They turned off the drinking water taps and electrical supply. They put up fences and the abandoned neighborhoods started to disappear under the rubble. The hospital was the first to fall: seven stories high, marble overlays on the floors, and a dense garden with enormous pines. In a month it was completely buried. There was a moment when only the two-meter chimney stuck out, a grey cylinder like the head of someone shipwrecked amongst the rocks. Later, only uneven rocks.

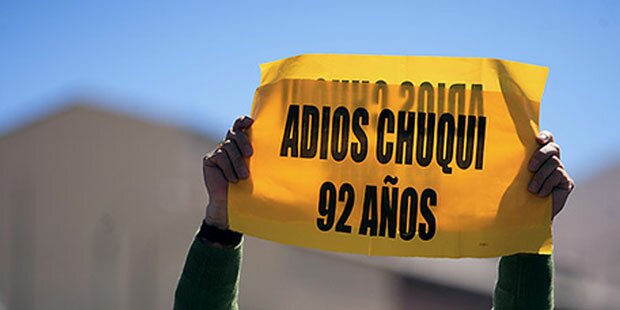

Chuquicamata emptied out like a big party that, all of the sudden, has ended. Before leaving, the inhabitants started painting the facades of their homes with goodbye messages. It meant nothing more than to do honor, to give thanks, to make the walls speak on their behalf:

GOODBYE, CHUQUICAMATA, THEY WILL TELL YOU WE LOVED YOU

HERE WE WERE CHILDREN

MY PETS FOREVER REST IN YOUR GARDEN

I LEAVE BEHIND MY BEST YEARS HERE

CHUQUI LIVES ON

At the same time, the social networks exploded as a site of collective catharsis. People far away who could not be there to say goodbye wrote: “I’m in Santiago and I’m crying from helplessness. Where will I return to?”. Some comments seemed like brief elegies: “It’s a shitty country that leaves me without my birthplace”, “I was happy at that wonderful mine”, “I miss you, Chuquito”, and a concise one: “It hurts”.

That was all. January 1, 2008 was day it closed down definitively. It wasn’t a symbolic goodbye anymore, but a now a painful, real goodbye. The camp was declared an industrial zone and access was completely prohibited. In absolute silence, Chuquicamata started its natural transformation into a ghost town.

The camp’s disappearance left its inhabitants without their history. People tried to reconstruct it through memories. They combated the loss in the decoration of their homes. When he arrived to Calama, Lucho Zavala — a 71-year-old man who had a newspaper stand in Chuquicamata — hung a black plaque with white letters on the wall of his new home. It was piece of his old home.

They had made him leave, and they had buried his house, but at least he could think that he still had the same address, that he still belonged to the same place, even if it was just his imagination. Lucho Zavala asked a Chuquicamata policeman for a favor: ‘I want you to bring me the plaque from the home where I lived. It’s A-1049. It’s on a corner.’ The man brought it. Now Zavala goes in and out his new home with the same address he observed for decades at the camp that today does not exist.

To get to Calama, you have to cross Route 24, a scar linking the two towns. When the sun heats up, Calama fills with lizards. Downtown, on Paseo Ramirez, there are couple of (decorative) pools, and in the pools there are four things: a Stalinist statue of a miner, a group of llamas, a cactus, and a sun made out of papier mache. It is a synthesis of the place. There, every morning, the former miners meet. Each day they seek each other out like members of the same extinct species.

Talking is a way for them to remind each other what they were, what they left behind.

Calama is a big bedroom with 140,000 who sleep in it. Codelco, which transformed the camp into a giant deposit of rocks, made Calama into a refuge for miners. In a 12-block radius there are 136 bars with their tinted windows and heavyset women. It has Chile’s highest per capita income but also the country’s highest cost of living, all in a city without roots, a crude, hard city imposed on a radical geography. Loaded with dirt, there’s barely a tree and the suicide rate is double the national average. The inhabitants of Chuquicamata always called it ‘Calama Calamity’, a place that incarnated everything negative, a place that was always distant to them: traffic, crime, uncleanliness, disorder. In Chuquicamata, on the other hand, everything was perfect. No one was conscious of the fact that in the streets there could be trash, stray dogs, or crooks. They were residents of a place where everyone knew each other, where doors were left open, bikes went unlocked, and cars were parked with the keys in them. During their first days in Calama, some people’s homes were robbed. If they left their bikes on the balcony, the thieves would force open the gate and take them. In Chuquicamata, this would have never happened.

But the move also affected Calama, which wasn’t prepared to receive thousands of new residents. The municipal budget couldn’t handle the demands of such a number of people. In lighting alone there were 6000 new streetlights. Some 10,000 new vehicles crowded the streets.

“Cities grow little by little, but this was like taking on half a city all at once. It caused a collapse,” says Luis Alfaro, Calama’s director of public works. (Codelco) had to provide resources to raise the electrical supply, improve the infrastructure on the roads, and maintain public spaces.

“That operation,” sums up Jarpa, “cost 500 million dollars.”

However, the big dilemma of the move was the culture clash: the daily routine in a camp is not like that of a normal city. For a miner, paying for services did not exist. They didn’t know what a neighborhood coalition was. Now they had to learn to pay bills, maintain their homes, and use public transportation. Many had their water and electricity cut: they couldn’t remember to pay the bills every month. In Chuquicamata, if the hot water heater didn’t work, they called Codelco and someone from the company would come fix it. If they broke a window someone would replace it. In Calama, one of the women went to the city and asked them to fix a window. They explained to her that it wasn’t anyone’s business but her own.

IV

During the summer of 1988, Gonzalo Cerda received an offer he couldn’t refuse. He was a mechanical engineer who worked as a university professor in Punta Arenas, at the extreme southern tip of Chile. One afternoon, when he opened the door to his home, he saw an enormous letter from Codelco on his table. Where it said ‘base salary’ there was a sum was five times more than he made as a professor. Without any real expectations, Cerda had sent his resume to the state. A few months later, at 33 years old, he would start working at the mine, at that time Chile’s best engineers school. He left everything to go to the other extreme of the country, to the desert.

Upon arriving in Chuquicamata, it seemed like the end of the world. He felt exiled, on another planet, alone in the middle of an immense expanse of sand. Little by little, however, Cerda found he had a very strong bond with Chuquicamata. What was it that happened in that place? For him, the secret was the isolation. In that geographic retreat, they only had each other. Together they created an environment that made the place manageable, attractive.

“It was a refuge,” he says. “In the effort of bearing it, the consolation was resting on people with the same reality. We needed to prove it: are you living through the same thing as me?”

Gonzalo Cerda belonged to the group of people who weren’t born in Chuquicamata, those who came from outside and left relatives in other parts of the country. That distancing caused solidarity between the new residents. Their loved ones were far away so the comrades formed their own families. It was a protected community without the jealousy and resentment of a normal society. No one envied their neighbor’s house. They all had the same possessions and enjoyed the same economic stability. It was different from other camps designed exclusively for workers without their families. Chuquicamata was not only centered around the work of the miners, but also around their daily life. It fomented overall well being through community activities and sporting events. When it was buried, it wasn’t just the town itself that disappeared, but also its way of life.

Today, the old downtown of the camp has been named a heritage sight, and it is — along with neighborhoods surrounding it — the little that remains standing. A hut guarded by Codelco verifies people’s permission to enter. Beyond the fence, lies a ghost town. In the central square, the children’s play area has turned into an exhibition of rust. Each swing set is an atrocity: an inert, immobile and unsettling piece like the patio of an empty school. At the ruins of the Liceo America, the blackboards are still intact with the last messages from the students, their goodbyes: ‘God damn contamination and god damn copper rubble. Why did you separate us? Why?’

The dry trees and boarded up homes are like warm cadavers. The street is a universe of subtle sounds: the banging of the corrugated iron, the creak of the branches, the footfalls in the gravel.

Behind a deteriorated gate are the remains of a garden. There is a woman’s handbag half buried, old shoes, and a tricycle, or the skeleton of one. Everything here is the remains of something, of some time, the remains of a life. Curtains escape through broken glass. Under a front window there is an anonymous revelation: ‘Here we first kissed’. Three kilometers away, the mine is still alive. It still spits gases and copper from an open mouth that takes in men every day. Inside the homes, however, is an interrupted space, empty, cut through by the urgency of leaving. In many of them, you can still see toothbrushes on the sinks, paper flowers, a useless coffee maker.

Papers float under a layer of dust: a Christmas card, notebooks from school, a shopping list. It smells rancid. There’s a yellowing kitchen calendar from the year 2004, January 12 circled in red. And then a cruel metaphor: the upright trunk — its roots dead on a rotting table — of a bonsai tree pulled out by its roots.

C.

C.

V

In the photograph, a man appears defeated. It is Christmas Eve, and in the photograph, Alcides Lira is going into his grocery store, La Verbena. An emblem in Chuquicamata for 55 years, it is lit up like every year at Christmas. From the door, Lira hugs his wife as both of them look out at the street: the darkness, the empty houses, the silence. This is what the image shows, a solitary spot of light in all of Chuquicamata. Today, at their new home in Calama, where the photograph is a way to hang onto to the history of the town, Lira’s children remember out loud:

“I brought with me here even the grass of Chuquicamata. I went to the hospital and stole a piece of turf. That is where I learned to play soccer.”

“Do you have a birthplace? I don’t. I was born in the Botadero 95, in what used to be the hospital in Chuquicamata. I am something that does not exist.”

“I worked in communications. I met with management and I knew what was going to happen with the camp. One day, after a meeting, I said to my dad: ‘The move is on.’ He responded: ‘No, Chuquicamata will never be over.’ My dad never believed it.”

Lira was the last to go. He kept sneaking back in for six months after they closed the camp. They cut off the water and electricity, but he used buckets and candles. He needed to go back, or at least needed to feel like he could, that he still had a home. The police convinced him: ‘You don’t have water. You don’t have electricity. You don’t have food. What are you doing here? Your family and friends are there with everyone from Chuqui. Now Calama is Chuquicamata’.

He lasted two years. On January 2, 2010, a stroke killed Alcides Lira. His oldest son thinks his father died from sorrow.

.

.

“He resisted being here up to his last moment. He was quiet all day. There are no statistics about what happened to the people who came, how many of them haven’t recovered.”

What is the exact distance in which one becomes an exile? For the last inhabitant of Chuquicamata, it was the 15 kilometers to Calama.

Translation for International Boulevard by Brian Hagenbuch.

Martina Bastos

21 Oct 2013