The protagonists of Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary The Act of Killing were part of the vast paramilitary killing machine created by US-backed generals to exterminate the Indonesian Communist Party after the 1965 coup. Old men now, they are celebrated as heroes, earn money as capos of mafia gangs, occasionally run for office; in their youth they helped to shoot, garrote and beat to death nearly a million people. Oppenheimer’s surreal and shocking film has inspired discussion in Indonesia, both about the mass killing, and about the ethical choices its American director made in creating the film.

Acclaimed in the Western press, the film was called ‘an act of manipulation’ by an academic specialist on Indonesia; another local reviewer writes that by failing to discuss the carefully planned and centrally directed nature of the killings, the film seems to paint Indonesians in general as “savage, exotic and funny people who slaughter each other nonchalantly,” rather than subjects of a military conspiracy. Excerpts from the debate in the Indonesian and regional press:

“THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS WHEN PERPETRATORS WIN”

Trailer for The Act of Killing

An interview in Cambodia’s Southeast Asia Globe, in which Oppenheimer describes the genesis of his film:

Southeast Asia Globe: You almost stumbled across this incredible story. How did The Act of Killing come about?

Joshua Oppenheimer: I first went to Indonesia in 2002 to make The Globalisation Tapes, a film about plantation workers struggling to organise a trade union. The main obstacle the workers faced was fear: there was a strong union until 1965, when its members were accused of being ‘communist’ and killed or imprisoned in the 1965-66 genocide. The people I spoke to explained that the killers were living all around us, that my next-door neighbour had killed one of the main characters’ aunts. The people were scared to talk about it but suggested that we interview the killers, saying that they would be happy – even proud – to speak to me. I was surprised, because normally criminals don’t boast of their crimes – unless, of course, nobody ever considered them crimes.

You interviewed more than 40 perpetrators for the film, but it all started with that murderous neighbour.

We began filming in front of my neighbour’s house and soon we were invited in. He was older, so I asked what he had done for a living. He answered, “I had been a security guard on the plantation, but was promoted to plantation manager because I exterminated 250 communist workers.” He then proceeded to demonstrate how he would beat the workers unconscious, and then drown them in an irrigation ditch. We wanted to know if other Indonesian killers spoke as casually and as boastfully about what they had done, and if so, why? For the next two years, I contacted every perpetrator I could, and found that this first man’s boasting was typical.

Despite its roots in a historic atrocity, you argue that this is not a film about the past.

I realised the story was not what happened in 1965, but rather what is happening now, in the present, that means these men feel comfortable boasting about their crimes. Obviously, nobody had ever said they were criminals. On the contrary, crimes against humanity were being celebrated.

This is what happens when perpetrators win, when mass murder and brutality are mythologised as heroic. We assume that perpetrators are normally held to account, or at least defeated, like the Nazis, the Khmer Rouge, the Hutu extremists. But perhaps those are unusual cases, the exception to the rule. Aren’t most societies built on violence celebrated as heroism?

The main protagonist, Anwar, is a very interesting and conflicted man. How did you want to portray him?

By the time I met Anwar I was explaining the point of the film very openly. I would say, “You have participated in one of the largest killings in recent human history. Your entire society is based on it. Your lives are shaped by it. You are eager to show me what you have done. Go ahead and show me.” The men in the film were not tricked into it. Anwar has seen the film and is very moved by it, and remains loyal to it.

I never forgot my condemnation of the perpetrators’ crimes, but I refuse to condemn them as ‘bad human beings’. The world is not divided into good and bad people. There are only humans, and some of us make terrible choices. When we make the leap from ‘human beings who commit evil’ to ‘evil people’, we denounce a whole person, and we feel entitled to denounce because we assume that we, ourselves, are good. If we build this fantasy, in which we are good, and all we have to do to prevent evil is exterminate the ‘bad guys’, how can we learn from history and prevent this from happening again?

Nonetheless, it is easy to be shocked by the attitude of the perpetrators.

The justification and even celebration of mass killings in the film seems like a sign that they feel no guilt, that they are inhuman. I think it’s the opposite. Murder is a human act, we’re the only species that does this and, if you can, justifying it is also human. These people can justify it, so they do, and this is actually a symptom of their own conscience and their own humanity. If you kill one person and justify it, and then the government asks you to kill another person for the same reason… Well, if you refuse, it’s like admitting it was wrong the first time.

You have said that one of the most moving scenes for Indonesians is near the end, when Anwar imagines his victims thanking him for killing them and sending them to heaven. Why is that?

Although I often see Indonesian viewers crying to that scene, they are also laughing at the same time. It is a joyful, cathartic laugh. It suggests that, finally, they see the underlying logic of their regime so nakedly portrayed by the killers themselves. The killers have taken off their masks, the regime has taken off its mask, and said, “Yes, we are shamelessly a country where we killed a million people. We got away with it, we’ve been in power ever since, and the victims should thank us for it. That’s the kind of morality our system has.”

It’s chilling, but it’s also joyful to see that exposed once and for all. Once it’s exposed there’s no going back and pretending that it’s not the case.

What has the reaction to the film been like in Indonesia?

The reaction in Indonesia has been positive and transformative beyond our wildest dreams. The film has forever broken the silence on the 1965-66 genocide. Everyone knew the country’s ‘democracy’ was a corrupt charade built on genocide; that any given politician might be a gangster or a mass-murderer – but no one dared say so.

– By Dene Mullen

“MISLEADING THE AUDIENCE, OMITTING THE HEAVY HAND OF THE MILITARY”

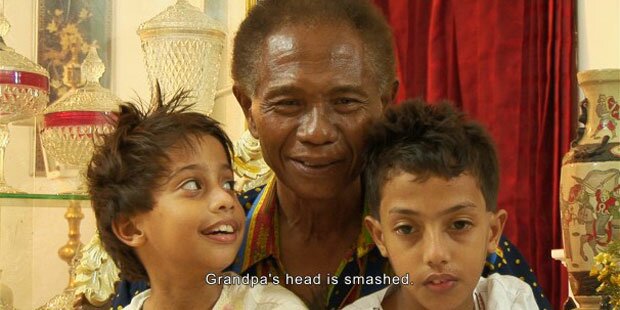

Anwar Congo demonstrates his efficient mass-garroting technique.

Anwar Congo demonstrates his efficient mass-garroting technique.

In The Malay Mail Online, Badrul Hisham Ismail writes that by focusing entirely on the men of a single local militia in Medan, the filmmaker does not show his viewers that the country-wide massacres of 1965-66 were centrally planned by the generals in Jakarta, and were part of the Western Cold War against the communist East:

Non-fiction or documentary film-making is a documentation of actuality to pursue two distinct and contradicting desires – desire for the truth, and spectacle.

Documentary film-makers often set out to capture “reality”, hoping to find something worthy of a story, and represent them to the audience to inform them of the subjects that he/she filmed, and at the same time entertain them.

Balancing these two elements is what normally raises a lot of ethical issues in documentary films, and “The Act of Killing” is not an exception to this.

Directed by London-based American film-maker Joshua Oppenheimer, “The Act of Killing” is about the Indonesian killings of 1965-1966. An estimated 500,000 to one million people were killed, which led to the elimination of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) as a political force, which at the time was the third-largest Communist party in the world.

But the film is not actually about the massacre. The film focuses on Anwar Congo and his “preman” friends, alleged perpetrators of the killings in the North Sumatra region, who were challenged by the film-makers to re-enact their killings into a film of any genre they wish. So they write the script, and play themselves and their victims, to realise their own memories of their killings. That is the premise of this documentary.

However, “The Act of Killing” shows very little of the actual film that Anwar Congo and his friends set out to make. Instead, it mainly shows the “creative process” that Anwar Congo goes through in filming the re-enactments – discussing about the small details of their actions, their killing methods, influences, and what they feel about the killings.

In its synopsis, the film promises a “journey into the memories and imaginations of the perpetrators”, and to expose a “regime that was founded on crimes against humanity.” But what resulted is a ridicule and degradation of Indonesian people, and we see almost nothing about the involvement of the people in power who ordered the massacre and those who benefited from them.

The issue that raises concern here is regarding the representation of the subjects of this film. A man with a very dark past, with the added value of being comfortable in front of the camera, and even more comfortable – perhaps unaware – in expressing diabolical thoughts and feelings.

Anwar Congo is a film-maker’s dream subject. A good film-maker would know that an interesting subject would make an interesting story, and like many other good film-makers, Oppenheimer did not miss the opportunity and succeeded in crafting a very interesting story.

As Anwar Congo and his friends talk about the filming and the crimes they committed, Oppenheimer lets his camera roll, recording the content of the conversation and in doing so, also captures their extraordinary personalities, creating an enthralling cinematic show to present to the audiences.

However, by only showing Anwar Congo’s side of the story, Oppenheimer risks misleading the audience on the true nature of the tragedy. In omitting the historical and political context of the massacre – besides a short text at the beginning of the film – and the heavy-handed role of the Indonesian military in it, Oppenheimer is not addressing the fact that Anwar Congo is just a pawn in a bigger political turmoil that was hitting the entire world.

The Indonesian killings of 1965-1966 were not just the work of a group of local “thugs.” It was ultimately a significant part of a proxy war within the Cold War era.

Oppenheimer scrutinizes his subjects’ personalities and exposes them to the world through a very ethically questionable method which resulted in making a caricature of the subjects.

By enticing them to film their memories and imaginations of the killings in any way they want, Oppenheimer reveals to the audience Anwar Congo and his friends’ bizarre and tasteless fantasies for no real purpose.

In the excerpts of the film that Anwar Congo makes, one of the gangsters called Herman Koto repeatedly appears in drag or tight pink dress. These repetitive and extended scenes do not contribute to the overall arc of the story and thus are deemed gratuitous. This leads us to question Oppenheimer’s intention, and what are his views, perspectives and opinions of the subject of his documentary.

Film-making, either fiction or non-fiction, is a delicate matter of revealing things. And as much as a film is about the subject, it also reveals something about the person behind the camera. For example, the film “The Dark Knight Rises” not only tells us about Batman/Bruce Wayne, but it also indicates that the director Christopher Nolan is pro-police and pro-Wall Street.

“The Act of Killing”, on the other hand, rightfully highlights the roles of the perpetrators of the killings, but in doing so we become aware of Joshua Oppenheimer’s view of the Indonesian people.

His framing of the Indonesians in this documentary is no different from an Orientalist’s view, where Indonesians are just another savage, exotic and funny people who slaughter each other nonchalantly because they do not value human life.

But unlike “The Dark Knight Rises” or any other fictional films, this film (like many other documentaries) presents itself as the truth. This is the danger of non-fiction films. They present themselves as absolute truths, when they are only partially true, seen from the perspective of the film-makers.

And it is important for the audience to bear this in mind while watching any documentaries. It is also important for any film-maker to assess these ethical issues regarding the representation of their real-life subjects before pursuing to document them.

In spite of this, “The Act of Killing” is still an important film that should not be ignored. Even with all its shortcomings and the ethical issues that surround it, this is an astonishing film that pushes the boundaries of non-fiction film-making, and still serves its purpose in bringing awareness of the horrific and tragic event of Indonesia’s history.

– By Badrul Hisham Ismail

“MANIPULATION, BETRAYAL, STAGED SCENES”

Surreal film-within-film: scene from Arsan Dan Aminah, in The Act of Killing.

Surreal film-within-film: scene from Arsan Dan Aminah, in The Act of Killing.

From Inside Indonesia, a discussion of the film’s omissions and insinuations by historian Robert Cribb, who despite strong reservations considers it an important work:

Filmed over several years in the North Sumatra capital, Medan, The Act of Killing is a sprawling work that encompasses three distinct, though related, stories. The core of the film consists of the reminiscences of an elderly gangster who took part in the massacres of Communists in 1965-66. Anwar Congo appears early on in the film as a genial old man, but his subdued charm evaporates as he begins to recount, and then to re-enact, the killings that he carried out. He takes the film crew to the rooftop where he garrotted his victims with wire to avoid making a mess with blood. Using an associate as a stand-in, he demonstrates the technique of slipping a wire noose over the victim’s head and twisting it tight for as long as was needed to bring death. One of Congo’s friends describes killing his girlfriend’s father, while another recalls his rape of 14 year old girls, exulting in the cruelty of the act.

The pleasure that Congo and his friends take in the memory of cruelty makes The Act of Killing a difficult film to watch. Not surprisingly, audiences have viewed it as a courageous revelation of the darkest secrets in Indonesia’s recent past. Yet the film’s depiction of the terrible months from October 1965 to March 1966 is deeply misleading. Although the opening text tells viewers that the killings were carried out under the auspices of the Indonesian army, the military is invisible in the film’s subsequent representation of the massacres.

The killings are presented as the work of civilian criminal psychopaths, not as a campaign of extermination, authorised and encouraged by the rising Suharto group within the Indonesian army and supported by broader social forces frightened by the possibility that the Indonesian communist party might come to power. At a time when a growing body of detailed research on the killings has made clear that the army played a pivotal role in the massacres, The Act of Killing puts back on the agenda the Orientalist notion that Indonesians slaughtered each other with casual self-indulgence because they did not value human life.

The film makes no attempt to evaluate the truth of Congo’s confessions. Despite persistent indications that he is mentally disturbed, and that he and his friends are boasting for the sake of creating shock, the film presents their claims without critique. There is no reason to doubt that Congo and his friends took part in the violence of 1965-66, and that the experience left deep mental scars, but did they kill as many as they claim? At times they sound like a group of teenage boys trying to outbid each other in tales of bravado.

There is no voice-over in the film. The protagonists seem to speak unprompted and undirected. Towards its end, however, the film portrays an incident which, to my mind, casts doubt on its apparent claim to present an unmediated portrait of the aged killer. Returning to the rooftop scene of the murders, Congo seems to experience remorse. Twice, he vomits discreetly into a convenient trough on the edge of the rooftop, before walking slowly and sadly downstairs. By this time in the film, Oppenheimer has made clear that Congo regarded him as a friend. Did Oppenheimer really just keep the cameras running and maintain his distance while his friend was in distress? Did Congo really think nothing of vomiting in front of the camera, under studio lights, and walking away as if the camera were not there? The incident seems staged.

The sense of manipulation is all the stronger in those scenes that present the second story. Congo and his friends plan a film about their exploits in 1965-66, and The Act of Killing is interspersed with both excerpts from the finished film and scenes of prior discussion and preparation for the filming. Neither the plot nor the structure of this film-within-a-film is ever made clear. Instead we see extracts that are alternately vicious (torture scenes and the burning of a village) and bizarre. A fat gangster called Herman Koto appears repeatedly in drag, sometimes in a tight pink dress, sometimes in a costume recalling an extravagant Brazilian mardi gras. Some scenes resemble the American gangster films that Congo tells us he used to watch; some are more like the modern Indonesian horror-fantasy genre, complete with supernatural beings.

The apparently finished scenes that we see from this film-within-a-film are slick. The cinematography is expert, the costumes and sets are professional. It seems too much to imagine that a retired gangster like Congo or a cross-dressing thug like Koto could have produced something of this quality on his own. Nor did they need to, with a professional film maker like Oppenheimer in house. Yet the film is presented as the work of Congo and his friends. It is hard not to sense a betrayal here. Congo and his associates seem to have been lured into working with Oppenheimer, only to have their bizarre and tasteless fantasies exposed to the world to no real purpose other than ridicule.

In the third major element in the film, Oppenheimer takes us beyond the confessional and the studio into the sordid world of the Medan underworld. Actually, it is hardly an underworld. Gangsters hold high government office, members of the paramilitary Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth, PP) strut through the streets, a gangster called Safit Pardede openly extorts protection money from Chinese traders in the Medan market, and the nation’s Vice President, Jusuf Kalla, attends a PP convention to congratulate the gangsters on their entrepreneurial spirit. The title of the film-within-a-film, Born Free, deliberately echoes the identity claimed by the PP for itself as preman, or ‘free men’.

Oppenheimer films the PP leader, Yapto, as an accomplished capo who can be suave or coarse as required. Another PP leader proudly shows off his collection of expensive European kitsch. ‘Very limited’, he grunts, self-satisfied, as he paws piece after piece. The condescension that Oppenheimer shows to the Indonesian criminal nouveau riche is unfortunate because it trivialises the film’s powerful portrayal of the shamelessness of the Medan gangster establishment and its close connections with political power.

Whatever might be criticised in the rest of the film, anyone interested in modern Indonesia will want to watch the scenes in which Safit Pardede prowls through the Medan market collecting cash from his small-trader victims. Manipulative and misleading The Act of Killing may be; it is nonetheless an extraordinarily powerful film which we should not ignore.

-By Robert Cribb

Further readings: Were the actor/subjects really aware they would appear in an American documentary about the massacres? Also, an Indonesian viewer in the US contemplates the disturbing humanity of the film’s killers. Finally, an assessment by an anthropologist who has studied the era of the genocide: revalatory and disturbing.

26 Aug 2013