‘Not Pakistani enough,’ a prominent Lahore art critic said of miniaturist Shahzia Sikander. But what makes an artist a national artist? asks Taymoor Soomro in Newsline. To be accepted as a Pakistani artist, it seems that one must either channel some ancient style of art, or critique (usually from a Western perspective) some aspect of Pakistani culture. Put a beard or a burka on it!

There’s something thrilling about public brawls. The unlikelier the brawlers, the better they are. A dispute between academics, in particular, is deliciously debasing. It’s the intellectual equivalent of a celebrity sex tape or a wardrobe malfunction and provides a glimpse of the bitchiness and professional jealousy ordinarily communicated in whispers during drawing room conversations. So, a disagreement that kicked off at the Lahore Literary Festival between some of the more eminent Pakistani art critics, and continued in the online press, was unmissable.

The dispute was about border control. In a slideshow presentation on Pakistani art, Quddus Mirza reportedly skipped over a slide on the miniaturist Shahzia Sikander saying, “Shahzia Sikander is not a Pakistani artist because she doesn’t engage with the community.” Faisal Devji, a reader at Oxford in South Asian Modern History, took umbrage and responded with a fiery essay lauding Sikander’s work, attacking Mirza and, for good measure, the critics Virginia Whiles and Iftikhar Dadi, too, for the censorship of Pakistan’s aesthetic history that excluded artists such as Sikander. Dadi and Whiles defended themselves eloquently in the comments to Devji’s article, stating that their work has been on other areas of art and their respective failures to write at length on Sikander was a question of focus, rather than censorship. Despite its vitriol, the disagreement raised some interesting points. What does it mean to be a Pakistani artist? What role should critics play in determining that?

At its simplest, to be a Pakistani artist could mean to be Pakistani and an artist. We could start with a measure of citizenship, but there’s a suggestion in Mirza’s statement and Devji’s response that that would be an inadequate measure, and I think it’s a suggestion worth exploring. As a Pakistani national, who has lived abroad much of his life and been perceived and treated as a foreigner in Pakistan, it’s something I understand. When I returned to live in Pakistan recently, I sensed in many the following attitude: “You abandoned Pakistan when it suited you (as so many do). Now it suits you to be Pakistani, you think you can pick it (or us), up again so easily?” I wonder whether this sentiment attaches at all to Mirza’s critique. In his words, to be Pakistani, one must “engage with the community.” There’s a suggestion here that a Pakistani artist must spend time in Pakistan with Pakistani artists and that his or her work must engage with local themes.

‘Pakistaniness’ was not a particularly useful attribute before the War on Terror. Since then, it has become both less and more useful. A Pakistani traveler abroad faces likely terror of his own every time he crosses a border. But with Pakistani fundamentalism, a regular feature in the news, commentators on the subject have an audience. That includes artists.

Pakistani artists who report on beards and burqas and the terror of daily life in a voice reassuringly at odds with the fiery fundamentalists the world imagines us to be, attract the powerful spotlight of the foreign press. It’s the new orientalism. And in place of harems and eunuchs and scimitars and concubines, in place of the sensuality and barbarism of the old orientalism, we have religious extremism and the oppression of women and a terrible, unhappy, seething, dark-skinned poverty. Given that the critical markets are overseas (Who are the Indians buying? Who’s selling at Sotheby’s), foreign appeal is determinative. Is your work Pakistani enough? And are you “Pakistani” enough?

So there’s a value to Pakistaniness for artists. And access to that platform is determined at the second instance by the content of the work, but at the first instance by a powerful cohort of critics (like Mirza, Whiles and Dadi) and curators who select the work that interests them and that they expect to interest their respective markets. Those determinations regulate the visibility of Pakistani art.

The power a very small group of critics and curators have in Pakistan is considerable. Relative to environments in which individuals have greater choice; In Pakistan, fewer can be artists, fewer can be critics, fewer curators and even fewer can be heard. The title of Devji’s article, ‘Little Dictators,’ recognised and attacked this inequity (though it wasn’t very fair in allocating blame). The American art market has its Gagosians and Zwirners who certainly wield extraordinary star-making and money-making power, but I imagine the distribution of control over participation in the art market is more widely spread than in Pakistan. That’s why the determinations thTo ey make on whom to, and not to, include in the canon of Pakistani art matters.

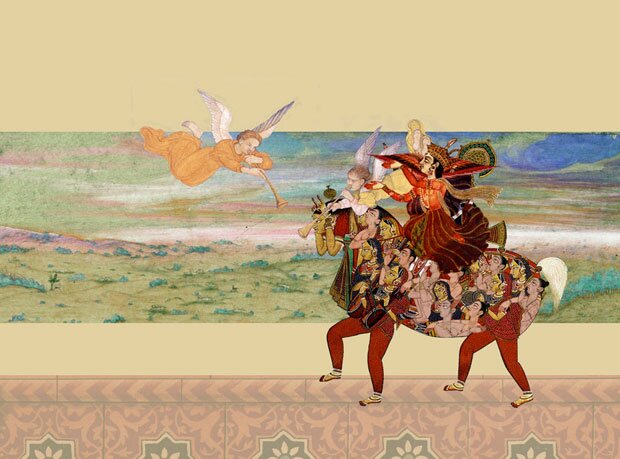

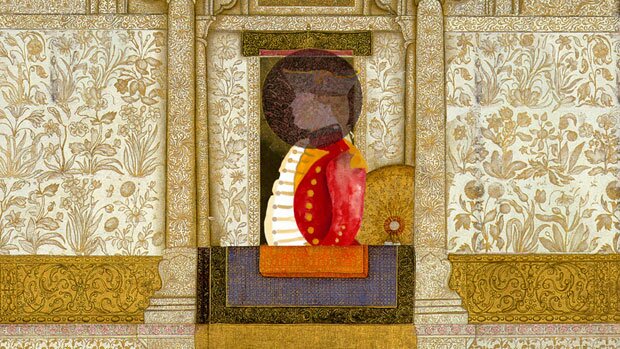

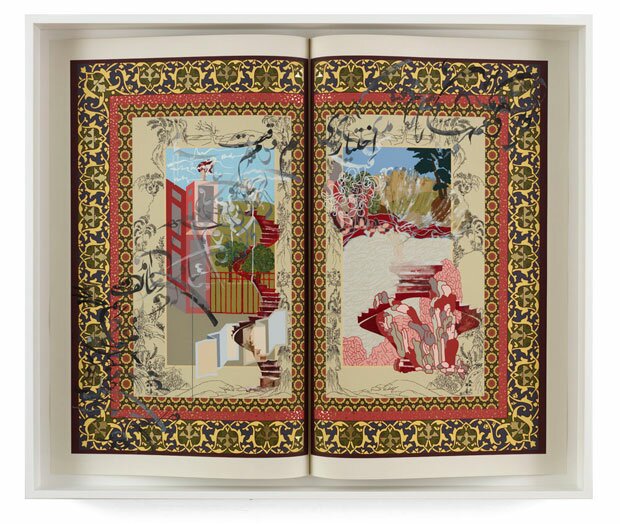

Sikander’s work is complex and often beautiful but I can understand why some might think the themes it tackles aren’t obviously Pakistani. They certainly aren’t Pakistani in the new oriental sense of the word. However, her extraordinary talent has attracted a wide audience. Writing her out of Pakistani art history won’t have much of an impact on her visibility (though it will have an impact on our understanding of Pakistani art). There are many who may not be quite as talented but have fascinating truths to tell. While those are not the obvious truths that foreign audiences want to hear, they will necessarily find it much harder to reach an audience.

This is neither an attack on critics nor an attack on work that tackles Pakistani fundamentalism as a theme. It is a call for more critics, more criticism and more visibility for work that tackles alternative themes.

Taymour Soomro

27 Jun 2014

By

By  By

By  By

By