The most famous goal in soccer history, 10.6 seconds of athletic genius that for millions of Argentines repaid in part the humiliation of recent defeat by England in the Falklands war. A quarter-final match, but for Orsai editor Hernan Casciari and every other soccer fan, this was the game that defined the 1986 World Cup that Diego Maradona’s team went on to win days later, the match they want to remember as this year’s World Cup begins in neighboring Brazil.

Less than 11 seconds earlier, when the Argentine player took the pass from his teammate, the clock in Mexico read 12 minutes and 20 seconds past 1 o’clock in the afternoon. In the middle of the scene there are also two Britons and an older man of Tunisian origin. The sport they are playing, soccer, is not particularly popular in Tunisia. That is why the African seems to be the only one who is not in a state of high athletic alert.

His name is Ali Bin Nasser and, while the others run, he walks slowly. He is 42 years old and humiliated: He knows that he will never again be asked to officiate an international game.

He also knows that, 12 years earlier when he injured himself playing in the Tunisian league, if they had told him he was going to be in a World Cup, he would not have believed it. Nor would he have believed it later, on the afternoon that he became a referee: In Tunisia, to reach that post it is only necessary to possess as many legs as you have lungs.

When he officiated his first match, he realized he was going to be a good referee. But it was more than that: He became the first soccer official to be recognized in the streets of the city. They called him up for the African qualifiers in 1984 and his work turned out to be so efficient that, a year later, he was called to officiate the World Cup.

In Mexico, they asked for his autograph, took pictures with him. He slept in the finest hotel. He had successfully officiated the Poland-Portugal match in the first round, and had watched the left sideline in the Denmark-Spain match in which the Danes played back the entire second half; he didn’t make a single mistake while raising the offside flag.

When the organizers told him he would officiate a face-off in the quarterfinals — a Tunisian referee had never made it that far –, Ali called home from his hotel, collect, to tell his father and both of them cried.

That night he slept anxiously and twice dreamed of the absurd. In the first dream, he twisted his ankle and the fourth referee had to substitute for him. In the dream, the fourth referee was his mother. In the second dream, an intruder jumped onto the field, pulled down his pants and left him with his genitals hanging in the wind on all the world’s television screens.

From each dream he awoke with heart palpitations. But he never dreamed, on that eve, of calling a handball a valid goal. He didn’t dream that, in Tunisia’s street slang, his last name would transform into a slang expression for blindness. That is why he is officiating the second half of this game, wishing all the while that it were over.

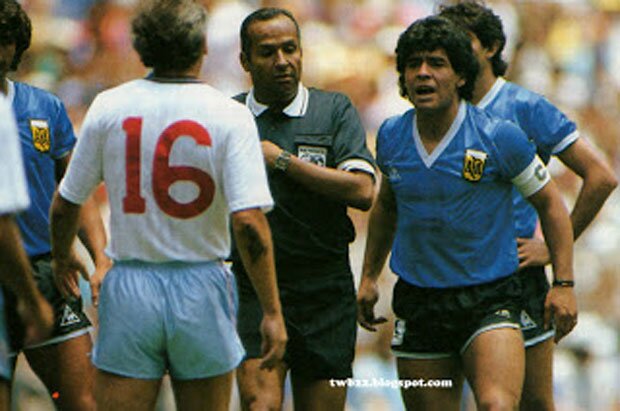

Argentina-England 1986. Referee Ali Bin Nasser starts the game of the century.

Argentina-England 1986. Referee Ali Bin Nasser starts the game of the century.

Around this field, hot, 115,000 people follow the movements of the player, but only two, the two closest to the scene, could possibly arrest his forward motion. They are named Peter: One Reid, the other Beardsley; they were born in northern England, one along the course and the other at the mouth of the Tyne River; the two both had, a few years previously, sons they named Peter; the two divorced their first wives before traveling to Mexico; and the two were both convinced, at 1 p.m., 12 minutes and 21 seconds, that it would be easy to take the ball away from the Argentine player, because he had received it with his back to the goal, and they were two: one in front and one in back.

They do not know that, a decade from now, Peter Reid Jr. and Peter Beardsley Jr. will be friends, they will be 15 and 16 years old, and they will both be dancing at a London rave.

A Scottish kid with the last name of O’Connor — who later will be a scriptwriter for the comedian Sacha Baron Cohen — will recognize them and, in the middle of the dance, dodge them with a feint and a sidestep.

He will do it once, twice, three times, imitating the dance step that now, ten years before, the Argentine player performs on their fathers.

Reid Jr. and Beardsley Jr. will not get the joke, and so other participants of the rave will join in on O’Connor’s taunt and a ring of dancers will form that, in the shape of human train, will dodge the boys in two beats.

Peter Reid Jr. will be the first to understand the ridicule, and will say to his friend: “It’s because of the video of our fathers, the one from Mexico in ’86.”

Peter Beardsley Jr. will make a gesture of humiliation and the two friends will escape the party, pursued by dozens of kids yelling, in chorus, the last name of the player who, ten years earlier, right now, is escaping from their fathers with a swish of his hips.

Very soon, father Reid and father Beardsley will stop pursuing the player: Attempting to stop him will be the work of other teammates. They are now frozen in the middle of the video that time transforms, in slow motion, from VHS to YouTube.

Now their kids are five and six years old and they won’t remember having seen the player’s first sidestep in person, but at the beginning of their adolescence they will watch it thousands of times on video and they will lose respect for their fathers.

Peter Reid and Peter Beardsley, immobile in the center of the field, still don’t know exactly what has happened in their lives to make everything implode.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona faces off with Peter Reid.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona faces off with Peter Reid.

Quick and with short steps, the Argentine player moves the scene into enemy territory. He has only touched the ball three times on his own side of the field: once to receive it and taunt the first Peter, the second time to stop the ball softly and get the second Peter off balance, and a third time to move the ball away toward the midfield line.

When the ball crosses the chalk line, the player has covered ten of the 52 meters he will cover, and has taken 11 of the 44 steps he will have to take.

At 12 minutes and 23 seconds after 1 o’clock, a hush of amazement drifts down from the bleachers and in the press booths the radio announcers lift their backsides from their seats. The hole in the defense down the right side that the player has just found, after his double sidestep and long stride: everyone understands the danger.

Everyone but Kenny Sansom, who shows up behind the two Peters and pursues the player with an absence of urgency that seems to come from some other sport. Sansom jogs along with the Argentine player calmly, as if he were accompanying a small child on his first bike ride.

“It looked like we are at practice, shit,” Coach Bobby Robson will say two hours later, in the locker room.

“That wasn’t you,” his half brother Allan will say to him a year later, both of them drunk at a pub in Dublin.

Kenny Sansom will rewind the tape thousands of times in the future. He will see his sluggish gait, almost a trot, while the player escapes him.

He will start, in November of that year, to have problems with gambling and alcohol. In the tabloids, they will nickname him “White” Sansom for his affinity for white wine. His only friend from the golden years will be Terry Butcher, perhaps because both of them will share the common ground of an identical trauma.

Butcher is the one who now, while the radio commentators and the spectators in the stands are still getting to their feet, will give him an ineffective kick as the player advances up the sideline. Butcher, crazed, will pursue the player, who doesn’t know that, in his rival’s language, his last name means butcher[carnicero], and will give him a second ineffective kick, this time with murderous intent, at the corner of the penalty area.

Terry Butcher will not be able to get over the ghost of those 10 seconds in the Mexican midday. “He beat the other players just once but he beat me twice… little bastard,” he will say to the press years later, with tears in his eyes.

Kenny Sansom and Terry Butcher won’t ever go back to Mexico, not even to the tourist beaches far from Mexico City. In the future, without children and stable relationships, they have an affinity (each almost 60 years old) for getting together and drinking whisky Thursday nights, and inventing new insults for the Argentine player who now, without anyone guarding him, enters the opposing field with the ball glued to his feet.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. England’s Kerry Sansom and Terry Butcher close in on Maradona.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. England’s Kerry Sansom and Terry Butcher close in on Maradona.

Before the start of the play, a man made a bad pass. That error began the story. He could have played the ball back or to his right, but he decided to turn it over to the least open player.

That man was named Hector Enrique and he remained motionless after the pass, his hands on his hips. After the game, he will not be able to separate himself from the player, as if the invisible thread from the vertical pass had transformed, with time, into a magnetic field.

Enrique doesn’t know it yet, but he will participate in another World Cup 24 years later on South African soil. He will form part of the staff for a coach that, fatter and older, will have the same face as the young man who now zigzags downfield. And he will end his career in the United Arab Emirates, again the right hand of the player to whom, seconds before, he has made a pass putting his back to the goal.

For many nights in the future, in a strange country where the women have to ride in the backseats of cars, Enrique will think about what would have happened if, instead of making that bad pass, he had given the ball up to Jorge Burruchaga, his second option.

Burruchaga is the one who now runs parallel, at the center of the field, to the player. It is 12 minutes and 24 seconds after 1 p.m.: He is convinced the player will pass him the ball before entering the penalty area, that he is only shaking off defenders to leave Burruchaga alone in front of the goal.

Burruchaga runs and looks at the player; with his body language he says ‘I’m open over the middle’, and while he waits in vain for the pass he does not know that, years later, he will accept a bribe in the French league and be punished by the International Federation. Another bad pass. But he, frozen in the present, still runs and waits for the pass that never comes.

Days later, he will make the decisive goal in the finals, but the world will only have eyes and memory for the other goal. Year after year, homage after homage, his will not be the most admired. One night, Burruchaga will call Saudi Arabia to speak with his friend Hector Enrique and will regret, a little jokingly, a little seriously, that goal made by another person that overshadowed his decisive goal in the finals. Enrique will then look out window at a sandstorm and, unintentionally, make Burruchaga smile. “That goal wasn’t that great,” he will say, “I made the pass. If he hadn’t made the goal, it would have been grounds for killing him.”

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona and Burruchaga celebrate the ‘Goal of the Century.’

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona and Burruchaga celebrate the ‘Goal of the Century.’

On the playing field, the wind is blowing at 12 kilometers an hour. If it had been blowing 60 kilometers an hour, as happened in Mexico City six days later, maybe the play would not have ended well.

His forward motion looks fast because of an optical illusion, but the player regulates his rhythm, slowing and faking. There’s a secret geometry in the precision of the zigzag, an exactitude that would have been broken by a shift in the wind or by the reflection of a watch face from the stands.

Terry Fenwick thinks about the random variables while he showers with his head hanging after the loss. Most of all one, the least ridiculous.

Before the game, Fenwick had advised Coach Bobby Robson that the best thing would be to guard the rival player man to man. Bobby responded that they would play a zone, as they had in other games.

‘What would have happened if Robson had taken my advice?’, Terry Fenwick will ask himself, naked in the locker room with water blasting his temples.

At this moment, at 12 minutes and 26 seconds past 1 pm, he is the one who sees the player arrive with the ball under control; he is the one who believes he will pass it to the center of the penalty area. Fenwick thinks the same as Burruchaga. He puts all his weight on his right foot to stop the pass and leaves the left flank open. The player, with a little hop, enters an empty hole, steps into the penalty area and finds the goal.

“Shit,” Terry Fenwick will say to the press in 1989,”he ruined my career in four seconds.” Two years after that outburst, in 1991, Fenwick will spend four months in prison for driving drunk. He will say, halfway through the next decade, that he wouldn’t shake the Argentine player’s hand if he saw him again.

Around that same time, one of his daughters will turn 18 years old. During the (birthday) party, Terry Fenwick will find her kissing an Argentine on a beach in Trinidad. He will recognize the boy’s nationality by the sky-blue and white soccer jersey with the number 10 on the back. Fenwick still does not know it, but as an old man he will coach an unknown team called ‘San Juan Jabloteh’ in Trinidad and Tobago, a country that never played in the World Cup, but has beaches.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Terry Butcher stands off the Argentine advance.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Terry Butcher stands off the Argentine advance.

Fenwick will get drunk every day in the sand on those beaches. The evening of the encounter between his daughter and the Argentine, he will try to approach the kid to punch him. The Argentine will dodge to the left and escape to the right. Fenwick will again be faked out.

The player will take eight steps out of the total of 44 inside the penalty area, and it will be enough for him to understand that the panorama is not favorable.

There is a rival, Terry Butcher, breathing down his neck from the right; another on the left, Glenn Hoddle, prevents him from giving it up to Burruchaga; Fenwick has recovered from the fake and is now covering a possible pass backwards and, in front of him, the goalie Peter Shilton is covering the closest upright.

The north, south and east are locked down to any move. It is12 minutes and 27 seconds after 1 o’clock. Three hours later in Buenos Aires. Six hours later in London.

In any other city in the world, at any time of the day or night, trying a shot on goal in the middle of that jumble of legs is impossible, and no one knows that better than Jorge Valdano, who is arriving alone, very alone, up the left side.

No one takes note of Valdano’s presence, neither now in the penalty area nor during primary school in the town of Las Parejas in the (Argentine province) Santa Fe.

Jorge Valdano sat reading Emilio Salgari novels while his classmates played soccer at recess, running in a swirl after the ball. Soccer seemed like a basic game to him at nine years old, but at 11 something occurred to him: He understood the rules and he noted, with surprise, that other kids did not play intelligently.

He started to play with them and, while the others ran after the ball without a strategy, he moved along the sidelines searching out the geometry of the sport.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona’s ‘Hand of God’ prepares to tip the ball past the English keeper.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona’s ‘Hand of God’ prepares to tip the ball past the English keeper.

And he was good. He played for two teams in the town and soon they called him from Rosario to play for the Newell’s farm team. He made his debut in the highest league at 18. At 20, he was youth world champion in Toulon. At 22 he had already played for the national team.

But in all those vertiginous years, he never loved the sport more than anything else. If they gave him a choice between a game amongst friends or a good novel, he always chose the book.

Up until that moment, at 30 years old, Valdano wasn’t sure he had chosen his true vocation. That is why now, as he waits for the pass, he finally feels that it might be his destiny, that perhaps he came into the world to kick that ball and bury it in the net.

He knows the player’s only option is to pass to the left. There is no other way out. While he steps into the penalty area, he thinks: “If he doesn’t pass it to me, I’m quitting everything and becoming a writer.”

But the player enters the penalty area without looking at him. Neither Butcher, nor Fenwick, nor Hoddle, nor Shilton notice (Valdano’s) presence. Not even the cameraman, who was following the play with the frame close, noticed him on time.

In the video, Valdano is a ghost whose entire body shows up just when the ball is at the top of the penalty area. Jorge Valdano still does not know it, but after that tournament he will start writing short stories.

There is no greater enemy for a striker than the goalie. The rest of the rivals can use their feet to trip or their knees to give them a blow to the thigh. It does not matter. They are legal weapons in a man’s game and the person attacked can return the blow on the next play.

But the picket, the rear guard, the goalkeeper, the goaltender (like Lucifer, his names are infinite) can touch the ball with his hands.

The goalie is an anomaly, an exception capable of taking down with his hands the best moves that men make with their feet. And up until that day, no soccer player had ever been able to return that affront in a World Cup.

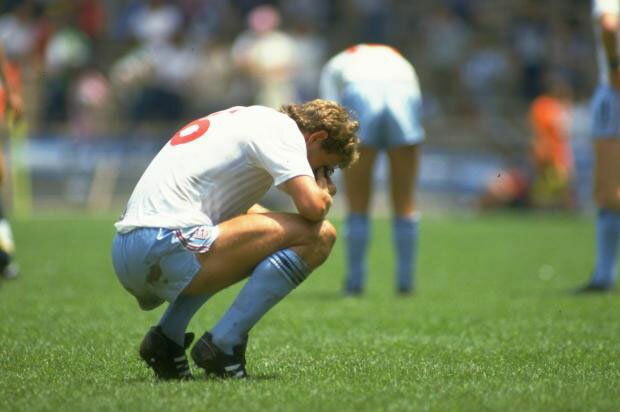

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Defeat looms for England.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Defeat looms for England.

That is why, now, when the player steps into the penalty area and looks into the eyes of the goalie Peter Shilton, (grey shirt, white gloves), he understands the hatred in the Englishman’s eyes.

Half an hour before, the Argentine had gotten revenge on behalf of all the strikers in the history of soccer: He had made a goal with his hand. The striker’s palm had arrived to the ball before the goalkeeper’s fist. In the rules of soccer, this is an illegal move, but in the rules of another game, more humane than soccer, justice had been served.

That is why, at this culminating moment of the story, at 12 minutes and 29 seconds after 1 pm, Peter Shilton knows he can get revenge on revenge. He knows very well that it is in his hands to foil the best goal of all time. Besides, he needs to do it to return to his country as a hero.

Shilton was born in Leicester, 36 years before that Mexican midday. He was already a living legend. It was not necessary for him to get his first and tardy World Cup to show it.

He still does not know it, but he will play as a professional until he is 48 years old. He will make so many unforgettable stops in the future that, added to the ones in the past, they will turn him into the greatest English goalkeeper.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona’s run nears its end.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Maradona’s run nears its end.

However (and he does not know this either) in the future there will be an encyclopedia, more famous than the Britannica, that will say this about him:

“Shilton, Peter: English goalkeeper who received, in the same day, the goals known as the ‘hand of God’ and the (goal of) ‘the century’.

That will be his karma and it is better he does not know it now, because he is still looking at the eyes of the Argentine player who approaches, and he is covering the left upright like his coaches taught him to do.

He thinks Terry Butcher can make it in time for a final leg swipe. ‘Maybe it will be a corner kick,’ he thinks. ‘Maybe I can take the ball away with the tips of my fingers.’

He also does not know that, two years later, in Great Britain there will be a video game in his name called ‘Peter Shilton’s Handball’, nor (does he know) that his children will play it clandestinely on vacation in 1992.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986.It is better he does not know the future now, because he must decide, right now, what the player’s next move will be. And he decides: Shilton plays to his left, throwing himself to the ground and playing a left crossover kick. The Argentine, who does know the future, chooses to continue to the right.

Before touching the ball a final time with his left foot, at 1 p.m., 12 minutes and 30 seconds in the Mexican midday, the Argentine player notices he has left Peter Shilton behind; he sees Jorge Valdano dragging along the defense of Terry Fenwick; he sees Peter Reid, Peter Beardsley and Glenn Hoddle have fallen off; he sees that Terry Butcher throws himself at his feet with cleats pointing out; he sees Jorge Burruchaga stop running, resigned; he sees Hector Enrique, still standing in the middle of the field, clench his right hand into a fist; he sees the coach jump off the bench like he has been ejected from a spring and another coach, the rival coach, look down to not witness his forward motion; he sees the man with the red hair and a smoking pipe in the first row of the bleachers; he sees the chalkline of the opposing goal and remembers the face of the employee who, at halftime, went over it with a roller; he sees clearly the face of his brother, El Turco, who, at seven years old, scolded him for an error he made at Wembley on a similar play; he sees his brother’s lips, dirty with dulce de leche, saying:

“Next time don’t crossover, you little shit. Better to fake the goalie and continue to the right.”

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986.

He sees his brother’s face in the light of the kitchen where the scene occurred. He sees the mischief in his face; he sees, behind the goal, a sign that says Seiko in white letters with a red background; he sees his first girlfriend’s nails painted green the day he met her, and he sees the same girl, a woman now, breastfeeding a girl; he sees a flat soccer ball and he sees himself, at nine years old, trying to control it; he sees his mother and his father who drag, with effort, an enormous canister of kerosene along a dirt road that has been rained on; he sees a name tag in the locker room in La Paternal that has his first and last names in brand new lettering; he sees with pride the adolescent read for the first time his first and last names on the name tag; he sees the stadium, its wooden stands, and he also sees that one day the entire stadium, not just the name tag, will carry his name.

The Argentine player has kept the air in his lungs for nine seconds, and now he’s about to let all the air out in one blast.

Opposite from all the rivals and teammates he has left along behind, he can breathe with his left leg, and he can also intuit the future as he advances the ball with his feet.

He sees, before time, that Shilton has thrown himself to the right; he sees Terry Butcher wants to cut him down from behind; he sees himself, many years later, with a grandchild in his arms, visiting the Estadio Azteca where they are raising a bronze statue with no name: just a young player with his chest puffed out, a ball at his feet, and a date engraved at the base: June 22, 1986; he sees a rave in London where two 15-year-old boys escape a multitude mocking them; he sees a dark apartment where there’s just a table, two friends and a mirror on the table; he sees a girl on a tropical beach who lets herself be kissed by a boy wearing an Argentina jersey; he sees a swarm of journalists and photographers outside all the airports, all the terminals, all the stadiums, and all the malls in the world; he sees the dead body of an old man who has died in Geneva eight days before that midday, a man who had also seen everything in the world at the same instant.

He sees (the slum where he grew up) Fiorito during the day; he sees Naples in the evening; he sees Barcelona at night.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986.

He sees the Boca Juniors’ stadium exploding with applause and he’s in the middle of the field but he’s not carrying the ball with his feet. He has a microphone in his hands; he sees an old man in the airport in Carthage [Tunis] who is waiting for his son coming on the last flight from Mexico to hug him and console him; he sees a swollen ankle; he sees a Red Cross nurse, pudgy and smiling; he sees all the goals he’s ever made and will ever make; he sees all the goals he’s celebrated and all the goals he will celebrate in his entire life; he sees himself at 53 years old watching from the box the World Cup final in the Maracana (Stadium); he sees the day he will see his mother for the first time; he sees the night he will see his father for the last time; he sees all his children’s children grow; he sees the birthing pains of a woman about to give birth to lefty from Rosario, a year and two days after that Mexican midday; he sees a tiny space, impossible, between the right upright and Terry Butcher’s shoe.

He closes his eyes. He lets himself fall forward, his body inclined, and the entire world goes silent.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Butcher’s last slashing attack fails to stop Maradona’s run.

Argentina-England, Quarter Final. Mexico 1986. Butcher’s last slashing attack fails to stop Maradona’s run.

The player knows he has taken 44 steps and kicked the ball 12 times, all with his left foot. He knows the play will last ten seconds and six tenths. So he thinks it’s time to explain to everyone who he is, who he has been, and who he will be until the end of time.

Translated by Brian Hagenbuch for International Blvd.

Hernan Casciari

04 Jan 2014