The farmers of the Andes have for centuries cultivated more than three thousand kinds of potatoes on the land where the plant was first domesticated; in the rest of the world, we always eat the same ones. From Etiqueta Negra, a profile of the most important guardian of the potato’s agrobiodiversity, the Lord of the Potatoes, a Quechua-speaking farmer who barely scrapes by on what he can earn from tilling and planting the hard and unforgiving soil of his native land:

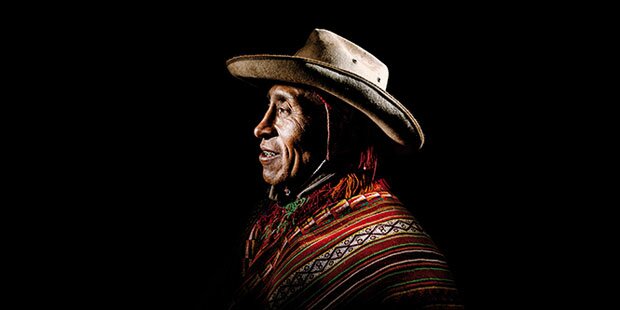

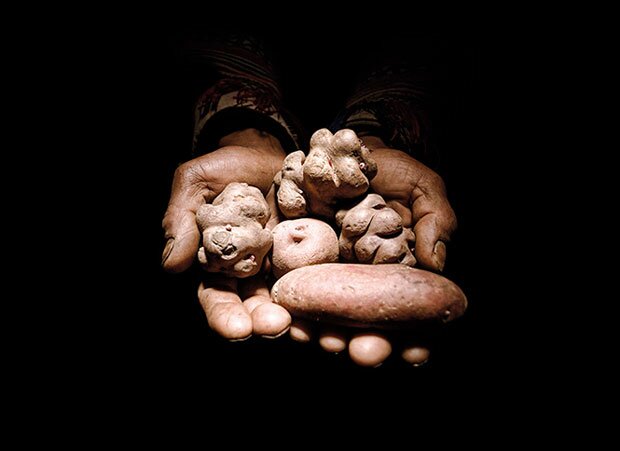

Julio Hancco is a farmer from the Andes who grows three hundred varieties of potatoes, and who recognizes each one by name: the one who makes the daughter-in-law cry, the scarlet pig turd, the cow horn, the patched old hat, the stiff sneaker, the spotted puma hand, the nose of black lama, the pig’s egg, the guinea pig fetus, the baby food to stop breastfeeding. These are not names in Latin, but rather names that their farmers chose to classify the potatoes based on their appearance, their taste, their character, their relationships with other things. Almost every one of the varieties of potatoes that Hancco produces here, over thirteen thousand feet above sea level in his land in Cusco, has already been named. But sometimes he grows a new kind, or comes across one that lost its identity over time, and then the Lord of the Potatoes can name it himself. The puka Ambrosio—puka in Quechua means red—is a variety that only grows in his land and that took that name in honor of one of Hancco’s nephews, who died after falling from a bridge. Ambrosio Huahuasonqo was a kind farmer, docile like mashed potatoes, and one who followed his uncle wherever he went and who won over everybody with his jokes. Some say that his Quechua last name defined his character: Huahuasonqo means “a child’s heart.” After his death, Hancco gave his nephew’s Greek name a new fate: Ambrosio means “immortal.” The potato that carries his name is long, smooth, slightly sweet, with light–yellow pulp and a red ring at its core. It’s a favorite of Hancco’s; this farmer who only speaks Quechua and has a name of Latin origin: Julio means “of strong roots.” It’s the spring of 2014. In his house, one afternoon, days after the seeding, Julio Hancco raises a hand as big and wrinkled as the bark of a tree, and points at a plate on the table.

“Like a son”—he says. “Like a son. That is potato.”

It’s so dark inside of Hancco’s house—a room made of stone, without windows and with an old table and a wood-burning stove—that it’s impossible to know if he’s saying it seriously or in jest. His wife, sitting on a small stool over the dirt floor, stirs a stew on the stove. A handful of puka Ambrosio potatoes grow cold on the dining table. They’re delicious, but most Peruvians will never get to taste them. We know potatoes originated in Peru, and that farmers in the Andes cultivate over three thousand varieties, but we don’t really know much about them. We know where iPhones are made, who is the wealthiest man in the world, the color of Mars’ surface, the name of Messi’s son, but we know almost nothing about the food that we eat everyday. If it’s true that we are what we eat, then most of us don’t know who we are.

In any market in Peru, a shopper’s biggest dilemma is choosing between white and yellow potatoes. They can recognize the Huayro potatoes—brown with purple overtones, particularly good to eat dipped in different sauces—get together with friends and eat cocktail-styled potatoes—those the size of mushrooms—or feeling more patriotic if they buy a bag of native potatoes—produced in lands over eleven thousand feet above sea level. However, like everybody else, they’re citizens of the French-fried world: Peru, the country that produces the biggest variety of potatoes in the world, imported twenty-four tons of precooked potatoes in 2014: the kind fast food restaurants use to make French fries.

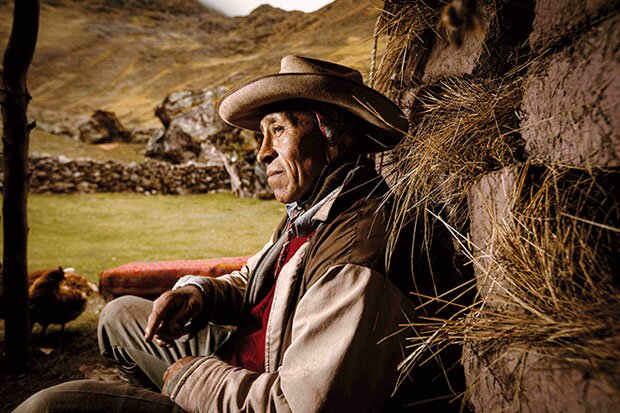

When he looks onto the snow-covered mountain across from his house, Julio Hancco fixes his gaze the way some people in the city do when they walk by a church: as if they were making the sign of the cross within themselves, making an almost imperceptible reverence. Hancco is a sixty-two year old farmer that has been called a custodian of knowledge, a guardian of diversity, a star producer. He was awarded the Ají de Plata at Mistura gastronomical festival and has hosted researcher from Italy, Japan, France, Belgium, Russia, United States, and producers of Bolivia and Ecuador that have traveled to his land in the in the farming community of Pampacorral to ask him how he manages to produce such a large variety of potatoes. Hancco lives thirteen thousand one hundred and twenty three feet above sea level, at the bottom of the Sawasiray Mountain, on a landscape of yellow soil, arid hills and gigantic rocks to which European engineers can climb, but cars and electricity cannot. To get to his house you have to get out of the car in the middle of the road and walk up over half a mile on a steep slope, something anyone not from here would describe as a mountain. Those who travel to see him from any city take their time on the walk: they gasp for air and get dizzy because of the lack of oxygen. Up there, blood runs slowly and the wind blows violently. In the summertime, water from the melting mountaintop glaciers gets so cold that washing your face becomes painful.

During the winter, temperatures drop to 14 degrees Fahrenheit, which can freeze skin in an hour. To get firewood, Hancco has to walk about three miles to a place suited for trees to grow, cut the logs and take them home on his horse. To get gas he has to walk down to the paved road and take a small combi van that takes him to Lares, the closes town, over twelve miles away, where he sometimes buys bread, rice, vegetables and fruit; everything he can’t grow on his land. The only things that blossom at the altitude of the land that he inherited from his parents are potatoes.

The potato is the first vegetable that NASA cultivated in space because of its ability to adapt to different environments. It’s the most important non-cereal crop in the world and also the one that has expanded the most. The plant that produces more food per hectare than any other crop. The hidden treasure of the Andes that saved Europe from famine. The main diet for Napoleon’s troops. The basis for the Spanish tortilla, the Italian gnocchi, the Jewish knishes, the French purée, the primitive Russian vodka. The delicacy that Thomas Jefferson served fried, cut in the form of batons, to his guests at the White House. The root of the purple flower that Marie Antoinette used in her hair when she scrolled down the Gardens of Versailles. The vegetable to which countries around the world have dedicated museums: three in Germany, two in Belgium, two in Canada, two in the United States, and one in Denmark. The root that inspired one of Neruda’s odes—”Universal treat, you didn’t expect my sonnet/because you are blind and deaf and buried”—a James Brown song—”Here I am and I’m back again/doing mashed potatoes”—two Van Gogh paintings—in one of them, by the name The Potato Eaters, five farmers eat potatoes around a squared table. The origin of thousands of seeds that are kept along with thousands of other species on a bunker underneath a mountain on the Norwegian artic in order to protect the richness of the potato from future natural disasters. The crop that Julio Hancco treats like a son, but that his younger children don’t want to produce because they don’t want to live a life of sacrifices in exchange for subsistence. Hancco says he prefers to be alone and for his seven children to live in the city, where they can find less demanding and better-paid jobs.

If he was his second son’s age—Hernán, who’s 29 years old and our translator—the Lord of the potatoes jokingly says that he would find himself a foreign girlfriend and move to another country.

One early morning, fifteen years ago, Julio Hancco woke up his son Hernán and told him to carry a rock the size of a soccer ball from his house to the Calca port, an hour and half walk away. Hernán Hancco, his second son, was thirteen years old back then and was accompanying him for the first time to sell potatoes in that city, the shopping epicenter of the region. To get to Calca at seven in the morning they had to depart at three and walk four hours, and Hernán Hancco’s baptism consisted on carrying that rock half way there. It was a test of stamina and acceptance that the producers of the area repeated with their children. A tradition that doesn’t continue anymore, Hernán Hancco would tell me later, while he sells the last bag of Sumaj chips—potato chips made out of native potatoes—in an Sunday organic fair in Lima. Julio Hancco’s second son moved to the capital of Peru almost a decade ago, right after high school, when he was twenty years old. He arrived in Lima with some four hundred soles on his pocket—about one hundred and thirty dollars—and the decision to study accounting and English. He was never able to complete his studies because work consumed most of his time, but he became a fundamental aid to selling his family’s potatoes in the capital of Peru. With Hernán Hancco in Lima, his father, his mother and his older brother, Alberto, could avoid the commission that middlemen charge them, and they only pay for the transportation of the potatoes. Even so, the profit is minimal. But things are worse for those farmers who have nobody to help them.

“That’s why some producers are quitting potatoes”—he says—”and are focusing on tourism.”

Working on tourism, Hernán Hancco explains to me, is like offering yourself as a beast of burden for the foreigners that come to Cusco to walk the Inca trail. For three or four days—the time it takes to hike up to Machu Picchu—the farmers carry tourists’ bags and luggage, that way the foreigners can be more comfortable. For a four-day walk carrying the luggage they can receive some two hundred soles, plus two hundred more as tip. About one hundred and thirty dollars total. For a bag of over twenty-six pounds of native potatoes they usually get twenty soles. About six dollars and fifty cents.

“And this means working all day, every day” he says.

The dimples that potatoes have are called eyes, but we never look at the eyes of potatoes. Potatoes have eyebrows on top of their eyes. They have a belly button, blotches on their skin, round, compressed, oblong, elliptic, long bodies. The most popular potato in the north of Tenerife, Spain, is ‘the beauty of pink eyes’. The Astérix potato, from Holland, has red skin, yellow pulp and shallow eyes. The catalogs describe the potatoes of the world by their humanoid characteristics, but they were, at one time, a savage species, bitter, unpalatable. Today, it’s the civilized solanum tuberosum. Just like tomatoes, eggplants or peppers, belonging to the solanaceae family, named that way because its leaves, stems, fruit and sprout have solanine, a toxic substance that protects it against diseases, insects and other predators. Although high doses of solanine can kill a person, there have never been stories of killer potatoes. The human being domesticated the potato more than eight thousand years ago in the Andes, when the Earth was coming out of the Ice Age and Homo Sapiens were trying out agriculture, their new invention, to get food.

The inhabitants of the Peruvian Altiplano were the first to learn to manipulate the potatoes in order for them not to be toxic and to make them bigger and juicier. The potato returned the favor by conquering the world.

One afternoon, writer Michael Pollan was in his garden seeding a potato that he had bought by catalog, and wondered if he had chosen that potato or if it had seduced him to seed it. Pollan, the author that changed the way in which we see our relationships with food, believes that ‘the invention of agriculture’ can be thought of as the way plants figured out how to make us move and think for them. From the point of view of the plants, Pollan writes in The Botany of Desire, the human being could be thought of as an instrument of their strategy of survival, not much different from the bumblebee that is attracted by a flower and that has the function of disseminating pollen with the genes of that flower.

In a 2014 winter morning in Hancco’s land, in front of a pile of lama guano, it’s fairer to think of the Andean farmers as partners of the potatoes and not their domesticators. Now, at 7:30 in the morning on a Saturday, Hancco, his two older children and his neighbor Julián Juárez, chew on coca leaves and drink aguardiente before beginning their task of the day: taking the guano of the lamas to a sown potato field, almost half a mile away, to fertilize the land. The lamas that wait beside us already know the routine. The men take their shovels and carry the fertilizer in sacks tall enough to reach their waists. They fill thirty nine sacks, they sew them shut so they don’t unwrap, they tie up each sack over the back of a lama, take the animals to the field, untie the sacks, spread the guano, and go back to the starting point to repeat the routine. Two trips are necessary for four men, two women, three dogs and forty lamas to fertilize almost five acres in six hours of work. When the procession of lamas carrying fertilizer carries on through the mountain, escorted by farmers, one thinks of a biblical scene, one of those imagines of old Holy Week movies. It’s a memory doubly false: there are no lamas and no potatoes in the Bible (For this reason, when Catherine the Great of Russia ordered to her subjects to grow potatoes, the most orthodox believers refused to do it). But knowledge encourages heresy: after seeing how four farmers fertilize a piece of land seeded with potatoes for six hours, one feels that one should kneel before them prior to chewing on one of them.

Julio Hancco comes from many generations of Hanccos who inhabited this area of Cusco “almost since the beginning of time.” From his parents he inherited the land, the animals and over sixty kinds of potatoes. In the last fifteen years, Hancco multiplied his inheritance and now produces three hundred kinds. His decision of rescuing and growing a bigger variety was, mainly, an exercise in ability. Like all of the farmers in the Andes, his productive property is a sum of irregular pieces of land dispersed in different altitudes. The mastery of Andean farmers is attributed to this difficulty: in a territory governed by slopes, each cultivable corner receives a sun, humidity and wind quota. The land exposed to the light through a hillside remains in darkness on the other side. A giant rock blocks the rain from a cultivable strip of land but protects another one from the wind. To survive in this territory, the farmers had to multiply their chances to feed themselves. They grew different potatoes in every piece of land, they trained themselves in the meticulous observation of each plant, they tried and created thousands of varieties, and became the kings of genetic fertility in hostile lands. It was a way of conjuring the future: more potatoes meant more possibilities for securing food in times of plagues, diseases, frosts, hail and droughts. Instead of controlling nature, which is what our industrial agriculture does, the farmers of the Andes adapted to it.

“Nature doesn’t have a cure” says Hancco while he looks towards the Sawasiray mountain and bends down to pick up a handful of dirt. He has just dumped the last sack of guano on the sowed soil, a strip covered by green moss that sinks if you press it with your hand. It’s a strip of land in a slope, in the middle of a hill, without any natural protection. Hancco can use his farming techniques and natural pesticides for the diseases and plagues, but doesn’t have a way to protect his potatoes from hail or frosts. It has been worse lately, he says: the weather has become fussier and more unpredictable.

In the seventies, when Julio Hancco was a boy and began growing potatoes along with his father, his vice was bread: little boy Hancco worked his own furrows on the dirt to save money and buy bags of bread when the vendors went by offering their merchandise. A Peruvian back then consumed on average almost five hundred and eighty five two hundred and sixty five pounds of potatoes every year. In the next decade, consumption decreased, and the downfall accelerated in the eighties, when farmers began to migrate to the city to escape terrorism. By the nineteen nineties, during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori, the consumption of the potato had reached a historic low: about one hundred and ten pounds a year per person. Those potatoes that vanished from the statistics, the agricultural engineer Celfia Obregón Ramírez would later explain to me, were replaced with foods like rice and noodles.

“Since noodles have more status and eating a chicken leg has more status than eating guinea pig, people began to hide their potatoes”—says Obregón, president of the Association for Sustainable Development (ADERS, for its initials in Spanish) of Peru and promoter of the National Potato Day.

In the presence of white rice, yellow noodles and pale chicken, potatoes with their dark skin renovated the stigma of underdevelopment and poverty that it has had for centuries, since they were discovered by conquerors and arrived in Europe in the sixteenth century, supposedly on the pantry of a Spanish ship. Two hundred years would be needed for the potato to be consumed routinely in the Old Continent. It had a story of rejection and seduction in each European country: the potato was considered obscene and aphrodisiac, the cause of leprosy, food of witches, sacrilegious diet of the savages. But Ireland didn’t doubt adopting it from the beginning: the farmers of that country, stripped by the English of the few arable lands they had, were dying of hunger trying to get food out of the miserable soil left to them. When the potato arrived in that country in the second half of the sixteenth century—supposedly by the hand of the English corsair Walter Raleigh—the Irish discovered that with a bit of almost un-workable land they could produce food for an entire family and their livestock. In the beginning, the potato saved Ireland from hunger. It was later accused of the poverty of that country: in a century, the population grew from three to eight million, because parents were able to feed their children with whatever little they had.

American writer Charles Mann tells the story of economist Adam Smith, who was a potato enthusiast. Mann says that Smith was impressed by the exceptional health of the Irish even though they didn’t eat much more than potatoes. “Today we know why:—Mann says in his book 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created—the potato can better sustain life than any other food when eaten as the sole item of diet. It has all essential nutrients except vitamins A and D, which can be supplied by milk”. And the diet of impoverished Irish men and women in the times of Adam Smith, explains Mann, consisted basically on potatoes and milk. The potatoes that grow today in over one hundred and fifty countries produce highest quantity of nutrition per area unit than rice or corn. One potato alone contains half the amount of vitamin C than an adult needs per day. In some countries, like the United States, it offers even more vitamin C than citruses, which are industrialized and of lower quality. What matters in food, explains engineer Obregón Ramírez, is the dry matter and its nutritional value: a white plain potato, for example, has on average 20 percent dry matter and the rest is water. That means that, of a potato that weights 100 grams, 20 of them is foodstuff. Native potatoes, which grow in higher altitude and in more extreme climate conditions than commercial kinds, have between thirty and forty percent dry matter. Their nutrition levels are more than double that of the common potato and have relevant amounts of iron and zinc and vitamin B. But, of course, the native potatoes have less efficiency, are more difficult to transport and their end price is higher. We still believe in that misleading myth that potatoes fatten us, and we don’t understand why we should pay more for a potato, even if it has a different color or an exotic shape, if a potato is a potato is a potato.

Studies on the Peruvian potato insist, as a repeating formula, in the need for protecting its variety and cultivating technique for one obvious reason: they were perfected by farmers over centuries in order to guarantee food in the most extreme conditions, to resist a frost, hail and droughts. It’s what the world expects with climate change: hunger and extreme conditions. But there is a more greedy reason to want to care for them: because they’re delicious. Unlike mass production of commercial potatoes, farmers of the Andes grow their potatoes with the idea of eating them, feeding their family first and sell the rest. New York chef Dan Barber, who became a spokesperson for the movement “Farm-to-table,” often says that it isn’t possible to make good food without good ingredients. The technique of a cook is irrelevant: whoever looks for better taste, looks for the best ingredients. “And if that is the case—Barber says—what you’re looking for is good agriculture.” In Peru, a country that has turn its gastronomy into a matter of patriotic self-esteem, over sixty percent of what people eat—its fruits and vegetables, its cereals, tubers and legumes—are produced by small farmers. The Peruvian gastronomic boom that has filled political speeches with pride over the last decade is the boom of the ingredients of Peruvian gastronomy. But the government transformed that boom into fireworks: in the national budget approved for 2015, only 2.3 percent was assigned to Small Agriculture, the lowest percentage of investment for this sector since 2010. A study by the International Potato Center by the name The Potato Center in the Andean Region, grows this paradox: the producers of the areas of highest altitude, which are the ones that posses the richest variety, are also the poorest.

The true homeland of a man is not his childhood: it’s the food of his childhood. Before starting a day of work, a Sunday at seven in the morning, Julio Hancco’s wife serves breakfast: rice pudding, bread with fried eggs, potatoes from their harvest, alpaca ribs and soup made out of chuño—bitter, sundried potatoes—with some sheep meat. Julio Hancco and his sons Hernán and Wilfredo, who must work the land during the day, repeat the soup twice. Hancco points at the plates, looks and me, and speaks Spanish again:

“Meat natural. Potato natural. Water natural. Everything natural.”

Hancco jokes around saying that, if he was younger, he would move to the city or to another country. But if you ask him in all seriousness, he says no: he wouldn’t leave his animals. But also—he says—at least in his land he eats what he wants. Here he eats potatoes and he eats pig, lama, alpaca, guinea pig, rabbit. In the city, on the other hand, everything is noodles, rice, and cookies.

“That’s not nutritious. Too many chemicals”—he says in Quechua, while Hernán, his son, translates for him.

The Lord of the potatoes was in Italy twice. Slow Food, an international movement that opposes industrially manufactured food and artificial flavors and seeks to bring back taste and traditional productions of food, invited him to the country. With the support of the National Association of Agroecological Producers (ANPE, for his initials in Spanish) of Peru and of Slow Food, which organizes the Salone del Gusto, Hancco and his sons were able to fry and pack hundreds of snack bags of native potatoes to sell in Italy. Their farming techniques, the same ones that the Andean farmers have maintained for centuries and that Hancco perfected in order to produce the variety of potatoes that he does, were now recognized as systems of agreoecological production. Julio Hancco doesn’t call his seeds ‘bastions of agrobiodiversity’, but every time that he participated of an event in Peru he was able to hear that his work was important for everybody. In the last fifteen years, Hancco and the producers of the region have received the support of non-governmental organizations to produce and sell their potatoes, to obtain water and adapt to the effects of climate change, and to design norms that favor family agriculture. Julio Hancco has harvested recognition, some press releases that hang on his sons’ room, many visits by foreigners, and a picture with Gastón Acurio, but he hasn’t harvested real measures by the Peruvian government. Nothing has changed much in his work conditions, nor in the conditions of thousand of other producers who, like himself, are admired by the world because of his work. From his trip to Italy, the Lord of the potatoes remembers enjoying the salmon, and the plane.

Eliezer Budasoff Translated by Maria Jesus Zevallos

30 Nov 2015