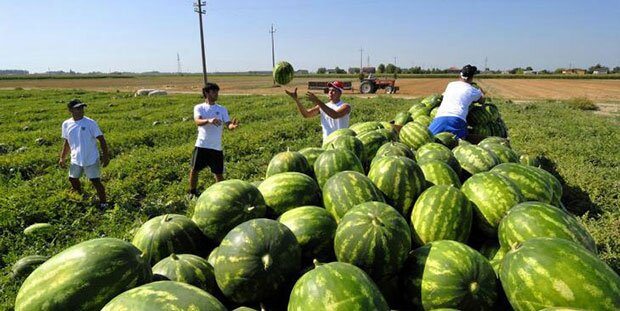

Exploited, underpaid and mistreated, the field laborers who harvest southern Italy’s crops have little official help. But the country’s labor unions are working from the bottom up to stop the practice of caporalato, illegal piecework labor gangs ruled in near slavery conditions by a foreman who answers to the mafia, writes Fabrizio Patti in Linkiesta:

“This August at dawn we would go out to see the field workers. We spoke with them, roundabout after roundabout, while from the pick-up trucks the caporali looked at us menacingly and sometimes got off the trucks. We took photos and we brought everything to the questura[provincial police]. And it worked. The questore was enthusiastic about our work and sent out inspectors.” The speaker is Tammaro Della Corte, a “grassroots” union organizer of the FLAI-CGIL in Castelvolturno, a camorra[Neapolitan Mafia] town known for the massacre of immigrants that took place there in 2008 at the hands of a breakaway group of the Casalesi clan.

For the past five years, Tammaro, together with a few colleagues, has been meeting the seasonal workers “in the only places where one can meet them, that is to say in the street, in the town squares. We follow a directive of the national union, but we also do nothing but follow the example of our teacher, [Giuseppe] Di Vittorio.”

Those who were killed seven years ago were six African farm hands, from Ghana and Togo, in addition to an Italian who ran a videogame arcade. A revolt of the African farm hands followed, opening Italy’s eyes to the condition of segregation of the foreign tomato pickers – as did the Rosarno clashes in Calabria two years later.

Today, Tammaro explains, the situation is one of apparent calm. A slender equilibrium that nonetheless any spark risks blowing away. Nothing apparently seems to change: the caporali [foremen], who are 80% foreigners, continue to domineer, even though they do not move a finger without the say-so of the camorra.

There are differences that make the situation less inhuman than in other parts of Italy: here the caporali, Della Corte explains, do not oblige the workers to purchase rides worth their weight in gold on minivans (5 euro) or bottles of water (1-2 euros); there have been no reports of farm hands forced to take drugs to combat fatigue, as happens for the Sikhs of Latina.

The price women are made to pay, however, is harsh: “often the border between the exploitation of labor and the exploitation of prostitution is a muddled one. In many cases women in order to be allowed to work must prostitute themselves.” Striking cases have been revealed by investigative journalism in the countryside around Vittoria, in the province of Ragusa, but the phenomenon is not limited to this area.

What has changed, with respect to past years, is that since 2011 the caporali may be subjected to criminal prosecution, with penalties from 5 to 8 years in prison. “There have been some arrests. The latest were in Puglia, and one near here, in Salerno. It is a good thing, but it is like when they arrest drug dealers, it’s not that this interrupts the drug traffic, unless one intervenes on other fronts, too.”

Seen from the grassroots, the proposal of the Minister for Agricultural and Forestry Policies Maurizio Martina to institute a sort of certification that guarantees that no worker has been exploited in the production and collection of fruit and vegetables appears reasonable. “Repression is necessary, but so are prizes for those who collaborate,” he comments. “I hope Martina does not behave like his Prime Minister and talks with the union. We have several concrete proposals to propose.”

Martina has employed very strong words against the phenomenon of caporalato, commenting on the death of the farm hand Paola Clemente, aged 49, who did not survive the extreme labor conditions to which she was subjected in the countryside around Andria. “Caporalato in agriculture is a phenomenon that should be fought like the mafia and in order to defeat it, it is necessary that everyone be mobilized to the maximum: government institutions, business, civil society organizations, and unions.”

Thursday, August 20th Martina explained the government’s plan to Repubblica: “Beginning September 1st, agricultural businesses will be able to join the “Network of quality agricultural labor,” composed by INPS, unions, trade associations.”

It will be a public system of ethical certification of labor, rewarding for the businesses that join it: they will have to guarantee full compliance with the rules regarding labor conditions. “The network –Martina added– must also be utilized by the system of large-scale distribution and of the food industry for their supply chains.” Ultimately, it will be the customers who determine the advantageousness of a transparent behavior on the part of the agriculturalists, any time they decide to purchase the certified products. Nothing different from what happens today with organic products or “dolphin-saving” tuna.

A certification of this kind would be a novelty at the national level and is finding support even on the Left. Even according to Tammaro Della Corte “large-scale organized distribution is the link of the chain that can change things.” However, hedging and counter-proposals are not lacking.

Dario Stefàno, a senator from SEL originally from Puglia, among the members of parliament who have followed the issue of caporalato most closely, thinks it is necessary to go beyond voluntary participation and sees the relationship between the public administration and agricultural businesses as the preferred road. “Every time a business needs to interact with the public administration, for a certification or a fee, it must state how much it produces and with how many workers. If there are inconsistencies, inspections should be launched.”

The FLAI-CGIL union has also fielded some proposals. Two foremost: the protection of the farm hands who denounce the caporali and the legal obligation, for the companies that hire seasonal farm hands, to do so through public employment agencies.

This last measure, Tammaro Della Corte explains, would be rendered necessary by the proliferation of “grey market” labor. Less common than the “black market” variety, it has nonetheless spread with regards to Italian and European Union workers (Bulgarian and Romanian) ever since caporalato has become a criminal offense. “Many many times work contracts are drawn up for 2-3 days, no more than five, for a season of picking that can last 3 to 4 months.”

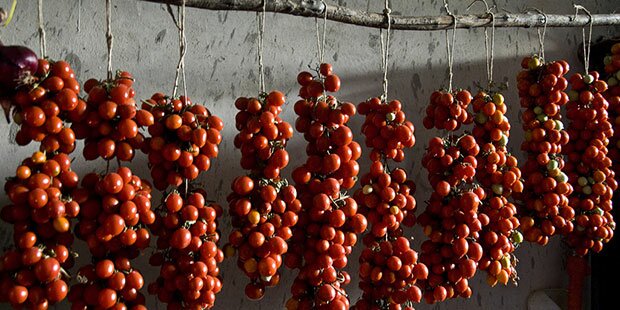

In other words, only a way to avoid being caught flagrante delicto. “One only needs to look at the lists of seasonal workers –he continues–: they are full of workers that are employed for a few days.” These lists came to be drawn up after the signing last summer of a protocol for social and ethical responsibility in the tomato preserves industry, for which unions and business associations were involved. As a Linkiesta article explained, however, the results have been very modest indeed.

Dario Stefàno is in agreement about the spread of “grey market” labor. “The phenomenon is organizing itself in an ever more slippery way,” he comments. “Agriculturalists are no longer directly involved, but rather it’s legal intermediation agencies who represent organizations for the criminal exploitation of labor.”

Is it a direct accusation leveled at employment agencies? “It must be ascertained whether diffuse unlawfulness is hiding behind these companies,” Stefàno answers. For the senator from Left Ecology Freedom it is urgent to institute a parliamentary inquiry committee on the phenomenon of caporalato, because “if we do not know the dynamics in detail, we risk fielding proposals that may even be attractive emotionally, but will be inefficacious.” A sentence that seems to mark some distance from the proposal that Stefàno’s party colleague, Arturo Scotto, Left Ecology Freedom whip in the lower Chamber, tabled on Thursday the 20th: to seize the assets of businesses that exploit workers, the way the assets of mafiosi are seized.

For Stefàno this parliamentary inquiry committee must be given the same powers as the Antimafia Parliamentary Committee, which “has the capacity to subpoena and almost absolute powers.”

Fabrizio Patti Translated from Italian by D. Lee for International Boulevard

28 Aug 2015