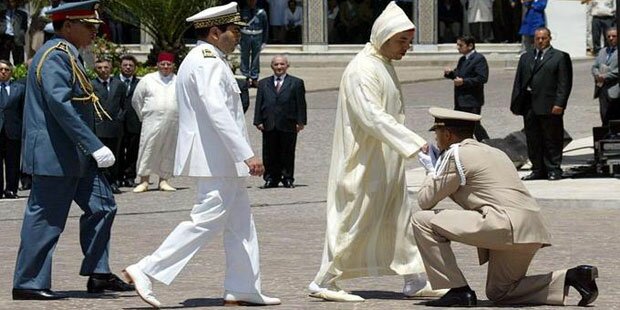

Ritual obeisance to the Moroccan crown can seem shocking, archaic write Driss Bennani and Hassan Hamdani. The images can be nauseating: grown men crawling on the ground to kiss the feet of their monarch, elderly generals bending double to kiss the hand of a child. Despite the crown’s promises to activists, the practice has survived Morocco’s Arab Spring.

“Kissing the hands of kings is something alien to our values and our morals. It is an act that all free souls refuse. I declare my categorical rejection of this custom, and call upon you to kiss the hand of no one but your parents, to show them your respect.”

The man speaking these words does not exactly have a reputation as a democrat. The country he leads is one of the most closed and conservative societies on the planet. Nevertheless, in 2005, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz took everyone by surprise by announcing the official abolition of hand-kissing in Saudi Arabia.

The Saudi king is seen, ironically, as something of a progressive by Moroccans who feel let down by the forsaken promises of Mohammed VI. At the beginning of his reign the Moroccan king had promised to lighten the royal protocol. The young monarch was perceived as a “cool” king who brought hopes of a new openness. Mohammed VI’s abolition of the practice of kissing the king’s hand was a sign of modernity that people waited for with much hope. But we are still waiting. And we are getting impatient, especially since discussion of this ritual – verboten for so long-is now in the news since the Arab spring began.

Feb. 20, 2011: the streets roar with slogans against corruption and despotism. The young protestors dream of modernity and democracy. Everyone is talking of a parliamentary monarchy. A few weeks later the king announces a constitutional reform; he promises to give up certain privileges to the prime minister. Political activists seize the occasion and bring back to the table the very symbolic (and thus very political) question of hand kissing. Abdelhamid Amine, vice president of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights, is seen on television demanding “the suppression of hand kissing and the ritual of prostration, which are contrary to the founding principles of human rights.” His statement strikes home. A number of intellectuals and politicians (among them several current ministers from the [Islamist] Justice and Development Party) join the call.

But the king remains silent. He allows a few weeks to go by, and then sends a new signal to the political parties, a message carried by one of his close advisors. In substance, the king says the following: “Only God is sacred. As for me, I prefer to be a citizen king.” What were we to deduce from this? Was the king finally going to strip away the protocol that surrounds his receptions, his trips, his official ceremonies? Nothing of the sort, as it turned out. The ceremony of allegiance that took place a few days after the new constitution was voted through, had not changed in the slightest. Hundreds of dignitaries, dressed in their white djellabas, prostrated themselves on the ground at the passage of the monarch riding on his horse, while servants of the royal palace chanted in unison: “God bless our lord.”

The customs of the Makhzen [Establishment] were followed to the letter; there would clearly be no retiring of the cornerstone of royal protocol: the kissing of the king’s hand. Modernists were shocked. Their hopes had been wasted, though the debate raged passionately on. It was revived in particular by an incident on Jan. 9, 2012, when the nine-year-old crown prince, Moulay El Hassan attended the inauguration ceremony of a new zoo in the capital. There he was welcomed by several senior officials who bent themselves double to kiss his little child’s hand. The heir to the Alawite Throne, amused, let it happen. The shock of the images was terrible. Everywhere, and especially in the Arab countries touched by the Arab Spring, the video of the incident made a scandal. The controversy in Morocco reached a fever-pitch.

In May of 2012, it was Ahmed Raissouni’s turn to join the debate. The former president of the [Islamist] Oneness and Reform Movement published an op-ed in which he stated that “In Islam, none should prostrate themselves except before God,” referring to the royal reception for regional governors newly appointed by Mohammed VI. Raissouni, a theologian very respected throughout the Arab world, concluded his essay saying that “religious texts are unequivocal on this subject: hand kissing is against the principles of Islam.” His op-ed had the air of a true fatwa. The coalition demanding the abolition of hand-kissing and other rituals of the Makhzen widened. Along with the political activists and progressives, religious figures began to join the fight.

“Each of these groups has its own reasons for opposing this ritual,” political commentator Mohamed Darif explains. “For the liberals, hand-kissing reinforces the notion of the people as subjects instead of citizens. For the religious, hand kissing is considered blasphemy. And in the name of modernity, young people who express themselves via social networks, see hand-kissing as an archaic relic, inherited from the past.”

The monarchy remains mute to the calls of intellectuals, politicians, religious figures and demonstrators calling for the official abolition of hand kissing. Since he took the throne 12 years ago, Mohammed VI has cultivated a deliberate vagueness on the topic. He either does or does not hold out his hand to be kissed, depending on the person and the political context.

At a reception organized to honor the members of the Royal Institute for Amazigh (Berber) culture on June 27, 2002, three years after he became king of Morocco, Mohammed VI confronted the first real challenge to the centuries-old ceremony. On that day, 40 Amazigh activists were officially nominated to the board of directors of the new institute, which had been created by the king. The activists agreed in advance that they would not ritually kiss the king’s hand.

The incident was without precedent, and was widely discussed in the press, with some considering it an act of rebelliousness. Which was an exaggeration. Numerous members of the group who refused to kiss the king’s hand have explained their gesture as a reaction to the breath of fresh air they felt in the period. They were no longer standing face-to-face with King Hassan II, the king who had denied the existence of an Amazigh identity, but with his son, Mohammed VI, who had finally accepted their existence. According to them, their refusal to kiss his hand was entirely in keeping with the new feeling of political openness that prevailed at the time. “Hand-kissing, symbol of a traditional protocol, was no longer obligatory before the new king, at the start of a new era,” says Ahmed Assid, one of the Amazigh Institute’s members. Mohamed VI showed no offense at their gesture of refusal, although those in charge of royal protocol insisted that the nominees bend to the traditional etiquette. The Amazigh activists chose to follow their ‘personal etiquette,’ the Institute’s director says. The moment powerfully underlined this [Berber] portion of Morocco’s identity, long suppressed under Hassan II.

This same attempt to break with the regime of the late king Hassan drove members of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission to refuse to kiss the hand of the Mohammed VI when he appointed them. The commissioners, charged with closing the wounds of [Hassan’s] bloody years– former leftist activists and opponents of the monarchy, veterans of years in prisons–were not about to bend over for the ritual kissing of the new king’s hand without feeling they were betraying their past commitments. The symbolism was powerful, the moment heavy with meaning, and could only be closed with a handshake, in this era when everyone seemed to want reconciliation.

Encouraged by a new constitution that no longer posited the king as a sacred person, and inspired by their victory in the legislative elections of 2011, the [Islamist] Peace and Justice Party ministers in Benkirane’s new government took advantage of the situation to alter the protocol themselves. To a man, they consented only to kissing the shoulder of the king, inclining their heads only ever so slightly.

Nevertheless. If bending before the king is now only a free choice for members of the Peace and Justice Party government, for Amazigh activists, and for human rights campaigners, the same cannot be said for the army, for provincial governors or for walis [regional governors]. For these, nothing has changed. New king or not, the rites, rules and ceremonies of the reign of Hassan II are enforced upon them. The heavy apparatus of protocol has the same coercive function now as it did with the late king: it affirms the political and symbolic supremacy of the monarch.

In an interview with [French Weekly] Paris Match in 2004, Mohammed VI said as much: “My style is different [than that of Hassan II], but Moroccan royal protocol has its place; I do want its rigor, and all of its rules to be preserved. It is a precious inheritance from the past…that nevertheless needs to be adapted to my own particular style.” Reading between the lines: this new particular style will allow no changes for those who directly represent the royal power of Mohammed VI.

Defending this rigidity, the king’s spokesperson (and onetime Director of Royal Protocol), Abdelhak Lamrini gave an interview to the weekly Maroc Hebdo, in which he announced that there would be no question of the slightest change in the ritual, particularly for people directly linked to the royal power. “The school of Moroccan royal protocol is a Makhzenian [Establishment] school, an ancient school; it holds to its traditions and customs, unlike other more flexible and considerably more supple royal protocols.” In other words, political analyst Youssef Belal writes, “the Palace remains very rigorous when it comes to the military and state employees; for those who are part of the state’s ‘hard power,’ hand-kissing is a mandatory passage to mark their submission.”

And what of ordinary Moroccans? The scenes of popular jubilation during Mohammed VI’s public crowd mingles, the spontaneous gestures that accompany these visits, show clearly that the population accepts hand-kissing unquestioningly. A poll by Tel Quel in 2009 showed that a majority of Moroccans favor hand kissing. How to interpret this reality? Mohamed Darif says it should be seen as a mark of the respect Moroccans have for a king who is a direct descendent of the Prophet. An obeisance to his ‘Sharifi’ status on top of the deference due to a king. “Whether those who oppose the hand-kissing like it or not, Moroccan society has internalized the practice as a form of respect for a king who is also a religious figure.”

For Darif, this ritual has been so strongly internalized that it is even common to kiss the hand of those who are close to the king, representatives of the earthly power of the monarch. By a kind of transitivity the hand-kisser is thus honoring Mohammed VI himself. “We all remember this image of this old man kissing the hand of [Interior Minister] Fouad Ali El Himma because he is close to Mohamed VI,” Darif says. “Certain people will even kiss the hands of provincial governors and walis.” Omar Saghi adds: “[Ordinary] Moroccans have their own little understandings of their political regime; the modernizers who oppose hand-kissing don’t always get this. Kissing the king’s hand, like kissing the hand of the Pope for a Catholic believer, is a gesture that is seen as an honor, a consecration, not the gesture of a slave.”

Finally, there is no doubt that the endless television broadcasts of this ceremony during the reign of Hassan II and now under Mohammed VI, have cemented in Moroccans’ minds that there is no alternative but to go through this ritual. Researcher Youssef Belal says that “television spreads the notion of servility [before the monarch]; it affects people and explains in part why ordinary citizens crawl all over one another to kiss the hand of Mohammed VI.”

Driss Bennani and Hassan Hamdani , Tel Quel

06 Jun 2013