An archaeologist obsessively excavating the catacombs of El Salvador’s endless unmarked graves, an attorney for the nameless victims of an undeclared war: a portrait of the solitude of a forensic investigator unlike any other, from International Boulevard’s Tomás Andréu:

One night he reached out for help on a social network. It was nearly midnight, and he had so many bodies to identify that he didn’t know what to do with them all.

El Salvador is a mass grave for victims of the country’s violence, the vast majority murdered by criminal gangs, maras. But one man works at the scenes of the crimes, pulls from the bowels of the earth the cadavers that have ended up forgotten, the crimes that put them there unpunished.

His name is Israel Ticas and he is the top crime scene investigator for El Salvador’s attorney general. He has studied in Central America, Mexico, Africa and Spain. He has neither replacements nor apprentices. He is one of a kind, a short man with strong indigenous features, always tanned by the sun. His efforts are a kind of work of art, but in spite of the beauty that he draws out of the horror, his daily work paints a picture of a country which devours its own citizens. Human lives are worth little here. Death may visit on the street or at home. No place is safe. Life itself is a spin of Russian roulette.

Many years ago, Israel Ticas told me that he spoke to the dead. My reply was that his job is to be a lawyer; I told him that he was a lawyer for the dead victims of El Salvador’s violence. He didn’t say anything. But he liked the idea. He is an expert in how Salvadorans barbarically murder their fellow citizens. He encounters it every day. He is a sort of Sisyphus, pushing his heavy burden somewhere every day only to find the next morning that he has to start all over.

El Salvador has been in an effective state of war for more than a decade. Those who were lucky have succeeded in fleeing to the United States. After the peace accords were signed in 1992 between the leftist insurgency and the government, the United States started deporting people back to El Salvador. The deportees brought with them the DNA of the gangs, which they cloned back into their home country. Neither the right-wing governments of the time, nor society at large could see the social time bomb that was now ticking.

The bloody tide that is drowning El Salvador flows from the two major gangs, the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), and the Barrio 18. The crime overwhelming the country seeps even into the government’s judicial and military system. Policemen, soldiers and members of the judicial branch are all targets of the gangsters, whom the Supreme Court went so far as to designate as terrorists in 2015. A predictably useless move, of course.

Common people have also become targets for acts as simple as crossing from one gang territory to another. Not even the president, Salvador Sanchez Ceren, is safe. Gangsters assassinated two of his body guards.

Everyone has to ask permission when they cross into a gang’s territory; politicians and preachers, salesmen and people who deliver water, soda, candy. Even a journalist who wants to take a picture must get authorization from a local kingpin.

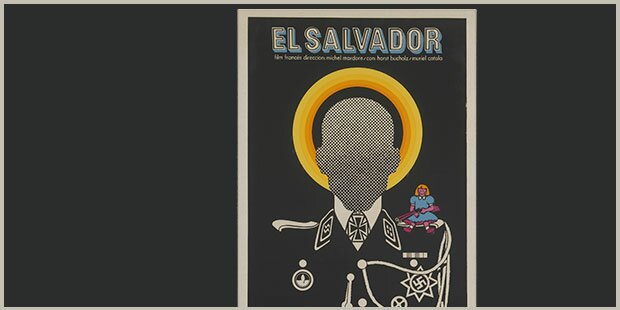

Quebracho. 1975. Photo: The Film Museum.

The most conservative estimates calculate that there are some sixty thousand gangsters on the streets of El Salvador and another thirteen thousand in the prisons. On top of these figures one must add the collaborators- from family members from the neighborhood to judges, policemen, soldiers, and low level politicians.

Though the country is called El Salvador — literally ‘the savior’ —, it doesn’t seem to be able to save anyone. That is a fact written on the bodies of the thousands of the disappeared.

Israel Ticas must find them for one simple reason: for him, the dead are not merely bodies; they are human beings with rights and families that deserve at least the right to a good sendoff. For Ticas, there’s no end for a human being worse than the cruel anonymity of a common grave.

This is the way he works: He starts with a clue; a report to the police. Once he has located the site, he ropes it off and begins a superficial search. It is the earth itself that will tell him whether or not it holds human remains within it.

The area studied takes on a particular texture, a certain humidity, emits a distinctive odor. It is all these irregularities in the earth that determine if he will begin digging. And that is where the wisdom of Israel Ticas comes into play, because experience and a silent reading of things is what guides him to the cadavers. It is not just about excavating. It is not about randomly digging holes. It is about arriving at bodies in an intelligent way for one simple reason: Along with the body is the murderer’s identity.

Little by little the scene begins to turn into a work of art that mixes architecture, acupuncture, engineering, anthropology, archeology, plumbing (drains in case of unexpected downpours), because the most important thing is to protect the crime scene and the evidence it contains.

The positions of the bodies are a testament to the final hours of the people who end up in mass graves. The lawyer to the dead begins to talk to them, soon knows who died first, who was buried alive, who was already a cadaver before going into the earth. It is terrifying to see how people struggled inside the graves. Hands in the form of claws: a sure sign that they wanted to get out, climb away from death. Facial expressions with the mouth open indicate a suffocated scream for help, or an attempt to get oxygen into their lungs.

The scenes show the evolution of violence in El Salvador. The murders are more and more horrifying, but also more sophisticated in their efforts to avoid leaving evidence that would tie them to their assassins. There is an effort to mutilate the bodies, to cut them up.

“Violence evolves quickly and destroys homes, families and people. Only death awaits to take us to the great beyond,” the crime scene investigator tells me.

In this little man’s hands rests the future of justice, the course of the investigation, the identity of the murderers.

While I spoke with Israel Ticas, he got a call from a mother looking for her son. The lawyer to the dead put her on speaker phone and she could be heard begging on the other end of the phone. She said that in the town of

Montelimar (La Paz province) several men took her son to a vacant lot. They came out later without him. The investigator explains to her what she must do: File a police report, send me a picture, and I will go to the lot and look for the body. Because the final and only consolation for families who have a missing relative is to get their bones back, bury them, have a place to leave flowers.

El Salvador seems at times more like a large cemetery than a country. In August 2015 there were 911 murders. That is 30 murders every 24 hours. That year ended with 6,670 murders. The North American newspaper USA Today dubbed it “The Murder Capitol of the World”. And 2016 has not brought brighter headlines. There are already more than 2,000 crimes and the numbers are mounting.

The figures on violent deaths have already overcome the daily violence of the war the nation experienced from 1980 to 1992, according Salvadoran authorities.

The paradox is that the country recently celebrated 24 years since signing a peace agreement. On January 16, 1992 the insurgent group FMLN and the administration of then-president Alfredo Cristiani of the ARENA party put an end to the war that left 75,000 dead and around 10,000 missing.

Felix Ulloa, the president of El Salvador’s Institute of Legal Studies (IEJES) and member of the political commission of the defunct FMLN, reflected in the online media outlet El Faro on the 24 years of what is called peace in El Salvador amidst this new context of violence:

“The gangs, which were initially just a product of the government’s indifference to the children of war, the orphans, the kids abandoned by their fathers who left the country to get by, they later grew up, got organized and multiplied and now they have us at their mercy”.

Pedro Paramo. Artist: Pena, 1969. Photo: The Film Museum.

The first scene that Israel Ticas investigated was that of the Jesuit priests from the Central American University (UCA), assassinated by the Salvadoran army in 1989, a case still looking for justice in Spain’s courts. The investigator was a policeman during the war. Back then, his specialty were terrorist attacks. Thanks to his meticulous nature, cases that seemed impossible to solve have been solved. And this is due to his close relationship with science and scientific investigation.

Living amidst death

Ticas likes working with cadavers, and he is proud of that. He calls them his friends, and he alone speaks with them. Each grave he works on is a way to polish his technique. He does not believe in perfection, but he knows he is not far from it. He brings together archeology, anthropology, architecture, acupuncture, medicine, even masonry.

He does all this because he is convinced that scientific proof is the best way to identify the killers. But he also knows that a country like El Salvador gives little importance importance to science. The country’s authorities prefer witness testimony over scientific evidence to solve crimes. He feels powerless when he processes crime scenes and then sees how the Institute of Legal Medicine throws cadavers in a plastic bags as if they were groceries.

“I feel bad when my colleagues do an excavation and it takes them less than an hour to do it. Those sites are rich in evidence”.

Smug and eccentric, Ticas knows he is the only one who performs his job artfully, with love and discipline, but like a bipolar child he gets sad because he would like to multiply himself and recover more bodies. He affirms that in El Salvador there are thousands of missing people. And missing is synonymous with dead. They are in clandestine graves and pits. Macabre pits, the media calls them.

“All these human remains hurt me, because they are humans and as humans they have rights. They have the right to go back to their families and to be buried like God wanted. It makes me angry that people call them rotten because they are still people and they deserve respect. Do you think that these people wanted their lives to end like this?”.

In El Salvador people live in a state of resignation; fear, pain, and paranoia are an everyday staple. And when a family loses one of their own to violence, they can only ask God that one day there be justice, because Salvadorans do not believe in their institutions. They know that the gangs have infiltrated the police, the army, the judicial system, and the prison system. Tjere is a kind of pragmatic wisdom that the gangs have imposed: See, hear, and keep your mouth shut if you want to enjoy your life. Inversely, there is death. If people respect this philosophy they will survive.

People say that Ticas is crazy, that he smells like death and that his excavations are holes like those of a 500-pound bomb. His colleagues think that doing so much for the dead is a waste of time. They think what he should do — more practical — is gather up cadavers without all the bureaucracy and put them in body bags. So much cynicism puts the investigator in a bad mood.

He has heated discussions with other investigators when they do not let him process blood, hair, semen and other evidence. The reason for not taking this evidence is because it comes from putrefied cadavers. But for Ticas the DNA is irrefutable proof, as much for the families as for the killers.

The lawyer for the dead comes apart when he investigates crimes where there are children involved. He cannot stand it. He sometimes has to do excavations where there have been children killed in the most sadistic ways.

Despite it all, he uses his “humanitarian shield” to move forward. Rest does not exist in Israel Ticas’ vocabulary. Being the best has a price. He works seven days a week. He can count his friends on one hand. Sometimes he does not go home and he sleeps in the office, an office decorated with skulls and other pieces of bone. The walls also have pictures of excavations he has done.

He gives the impression that he feels like a rock star who has done a long tour and has taken pictures of his activities. One cannot talk to Ticas about hell. He has already seen it all. He has already seen the darkest side of Salvadoran society: decapitated children, men with their penises and testicles cut off and put in their mouths that have been sewn together. Faces without eyes or teeth or skin. Women with beer bottles in their vaginas and anuses.

And the list goes on and it is macabre. Nazi concentration camps could not compare to the individual sadism El Salvador offers. And the violence gets more and more savage and sophisticated. There is an insatiable thirst to do harm and to be more and more perverse.

Despite the fact that violence rules El Salvador, Israel Ticas is neither in favor nor against government institutions. He stays on the margins and does not voice his opinion.

He does not like direct questions. For example, I asked him if the Salvadoran government had lost the battle on gangs and if the country had gone down the tubes. He smiled, and his smile turned into a laugh when he said: “I’m not going to talk to you about that. I know what it happening in El Salvador and what is going to happen, but I’m just going to talk about my work as a crime scene investigator”.

The lawyer to the dead does not mention the issue of investigations. He just does his job and lets the justice department do what it has to do. He does what he does because dying in El Salvador from violence almost assures someone will end up in silence. That is what happens when there is impunity and one becomes a target of these serial killers. Assassins walk the streets in all corners of the country. Here there is more blood in the streets than drinking water in the houses.

The rest of it is police business, Ticas says.

He is, of course, afraid for his safety, for his life. The place where he lives is like all other places, ruled by gangs. They see each other and exchange cordial greetings. From the news on television the gang members know what he is doing, but when he arrives in their neighborhoods they just make fun of him. They ask him if he happens to have an extra femur on him because one of the gang members is hurt. He tells them yes, that he has a female femur, but he isn’t sure if it will work for what they are looking for. Everyone laughs. A sense of humor is seriously important to stay alive in El Salvador.

The work of the lawyer to the dead consists of getting to the bodies in the smartest way possible. The process of exhuming can start at the feet or at the head. That depends on the site. Later he forms mounds that support the body by creating columns of earth underneath the elbows, the knees, the ankles, the chin, the head. In this way he can take pictures of them and see the scene in different dimensions. His only ongoing training is his daily work with the cadavers. He is always learning.

Los Fusiles. Photo: The Film Museum.

At the end of the workday, he ends up with a graphic depiction of how the bodies were introduced into the clandestine grave. The evidence is intact. The details provide an idea about what happened. He can determine whether the victims were killed by being buried or were thrown in and buried after being killed. This knowledge is crucial to determine whether witnesses under state protection are telling the truth or not. Israel Ticas does not like this much. He think that witness testimony should be that last recourse. He thinks scientific investigation should come first in the solving murders.

The lawyer to the dead treats the cadavers in an almost fatherly way. Once the crime scene has been excavated, he cleans the bodies with a brush. He does it softly. Piece by piece, he does it with the patience of a monk. And while he does it, he seems to be talking to the bodies. He checks to see if they have tattoos, wounds, signs of gunfire, bruises or contusions. He checks them down to their fingernails. It is important that the cadaver not move even a fraction of an inch because that could hurt the investigation. It is vital to not contaminate the crime scene. But all of his efforts go down the tubes when the Institute of Legal Medicine shows up and carelessly throws the cadavers in bags. And the only thing they say to Ticas is: “What a beautiful job you’ve done on these cadavers”.

Sadly for El Salvador, Ticas will leave no disciples behind when he dies. No one likes to work with the dead and even less in the way he works with them, with mysticism and discipline. He gets in holes full of putrefied water and feces. He plunges himself into all that rot and does his job like an artist. He has skin diseases, but he been able to keep them at bay.

“For a person to do what I do, he has to like putrefaction. He has to be immune to pain. He must not have feelings when it is time to go to work, because if that happens he will not do a good job. He will lose evidence. And this is the important thing, because he will let crimes goes unpunished if he does not do his job right. I work Saturday and Sunday. I don’t go on vacation because there are so many people buried. My work is important because I preserve evidence and the killer is in that evidence. I have a commitment to the dead. I would like to multiply myself and exhume all the dead in El Salvador’s clandestine graves, but I can’t. I feel impotent”.

Israel Ticas trusts the dead more than he trusts the living. He calls them friends that do not hurt him. He knows they will kill him, that he will not grow old or retire. He just hopes they kill him without warning, quickly and painlessly. And he wants his epitaph to read: “Here lies a man who wanted to help those who suffer and did not have enough time to do it. But if I can help a dead person, look for me and I will do it”.

Tomás Andréu Translated from Spanish by Brian Hagenbuch for International Boulevard.

17 Jan 2017