To the mountains of Bolivia every year come dozens of Peruvians and Japanese, there to buy rare insects and spirit them out of the country for sale in the markets of the United States, Europe and Asia for thousands of dollars. The business of catching beetles in Bolivia: from Anfibia Magazine.

When a trafficker asks him for an order, Limber packs his truck with portable lights and a few glass jars and drives an hour along dirt roads to the closest hill, some 6,500 feet high. Before night falls, he sets up a tent in the middle of the thick vegetation, drinks a couple of beers and lies down until four in the morning.

Awakened by his alarm, Limber starts hunting by turning on two large lights he carries on his back. He looks like a huge lightning bug illuminating the jungle’s darkness. With luck, a black beetle some five inches long will bounce off his lights. He then opens a jar and captures it. He has just bagged 100 bolivianos ($14).

Limber works in the coca fields and as a taxi driver. But for the past few years he has also taken up hunting the Dynastes satanas and Dynastes hercules beetles, species with powerful pincers. “Before, when I saw them I would squish them or just let them go. They grossed me out a bit,” he says after crawling out from under our car. In his free time, Limber is a mechanic. He is 30 years old, but still has the face of a roguish kid. His almond-shaped eyes look on suspiciously and almost all of his sentences end with a crooked grin. He lives in Yolosa, a small community in the municipality of Coroico, about 60 miles from La Paz, Bolivia. He and his wife live in a very modest, 320-square foot home. Next door is a half empty store and a few feet further on is another ramshackle home. During the day, the dusty street is empty. Only now, at around five in the afternoon, do the inhabitants begin to come down from their farming plots. Limber tries to fix our transmission. In the store, they sell bags of coca leaves; Timoteo, another neighbor, carries in the day’s produce on his back.

“That man was a human traffic light on the highway of death,” says the cashier. Timoteo was once in charge of directing the traffic on an extremely dangerous stretch of road linking La Paz to Coroico, but with the new road, which doesn’t come through here, went his job. The community’s half-dozen rundown eateries, with spent chalk boards offering up carne asada and rice, no longer have any costumers.

Surveying this panorama, Limber thought it a good idea to start looking for insects, after his uncle Porfirio, talked to him about the business. Three months a year, from December to February, Peruvians and “Chinese” — this is what the locals call them, though they are really Japanese — arrive, ready to pay money for insects to illegally take them out of the country. “Right now I don’t have any beetles. When I come off the mountain I give them to the person who made the order. I went up a week ago. When it’s cloudy like this they don’t appear,” he says, cleaning grease from his hands.

In other surrounding Aymara communities, the inhabitants wake up to pings on their metal roofing. In the Santo Domingo, five minutes outside Yolosa, small light bulbs surround Don Porfirio’s home, forming something like a spiderweb.

“He went to La Paz for supplies. He goes every week,” says his niece, Jesusa, a shy 30-year-old taking care of her twins.

While the kids play with the roosters pecking at the sparse grass, Jesusa tells about how, at dawn, the beetles throw themselves against the lights.

“That’s why we call them bulb-breakers.”

The hunters catch them and put them in glass jars, feeding them on plantains until they sell them. The house, little more than a concrete shell, is visited by the same trafficker every year. “He’s Peruvian, a family friend, but I can’t remember his name right now,” she says, embarrassed.

The family friend lives with them for a month, paying for food and chipping in for rent. When the insect season is over he collects the merchandise and disappears until the following year. He takes with him an average of 90 beetles from Porifio’s home, leaving behind about $1260, or $420 a month, a considerable amount in Bolivia, where minimum wage is $172 a month. Sometimes, however, as with all illegal businesses, the numbers aren’t clear.

“You remember Miguel, the Peruvian? He’s here already,” Limber says to an acquaintance while we are sharing a beer at the store. “He still owes me money from last year.”

Limber’s knowledge of the business of trafficking insects ends when the money changes hands for the insect.

“Do you know what they want the beetles for?” we ask him. He grins, shrugs his shoulders and shakes his head.

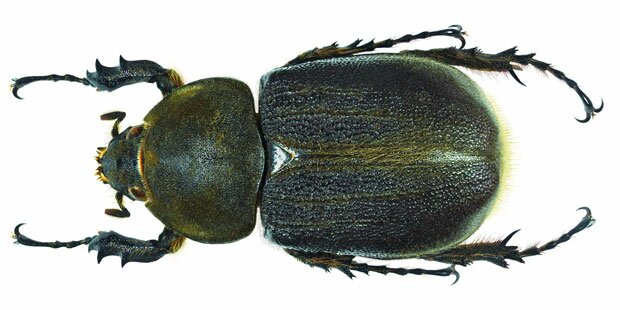

Golofa Eacus (Rhinoceros Beetle). Photo: Udo Schmidt

In Japan, Kabutomushi is a superstar. He has his own cartoon character, books, and video games; it is common to see his fights rebroadcast on TV. To get to Asia [from Bolivia], this insect must travel 10,278 miles in a 0.6-cubic inch, carefully-packed box, sometimes hidden in the mail, or other times in the hands of professional mules who, upon arrival to their destination, can sell them for around $300-that is if they make it to their destination. They only have a 50 percent chance of living, and even if they do make it, Kabutimoshi don’t live more than nine months. Japan has developed an incomprehensible love for these creatures. While in the West, the logical reaction upon seeing the insect is to squish it, in the East people feel affection for it. Children ask for Dynastes satanas or hercules for their birthday, to keep as pets. People raise them. The same thing happens with butterflies. It is a Japanese tradition to let 500 of them go during weddings to bring luck to the couple. Also it is believed that whispering a desire, preferably erotic, to a butterfly will make the wish come to fruition because the butterfly passes it on to the spirit in the skies.

On the Internet one can find an entire world dedicated to collecting insects, and people willing to pay $2500 for a Prepona xenagoras, one of the rarest Bolivian butterflies and among the world’s most valuable. There are people who look for the strangest species, the most exotic female, or simply want to have one from each continent. Some collect by color, texture, size or origin. Others look for insects for decorations, love of science, or to eat them, as is the case in Mexico. In some parts of Europe they use ants for therapeutic purposes.

Insects — mostly beetles and butterflies, although there are other odd species like the stick bugs — can be worth anywhere from 50 cents to thousands of dollars. Rare ones are more valuable… Sites like ornithoptera.net, mrozekinsect.com o latiendadelasmariposas.com have advertised species from $450 to $3000.

“In the 1980s I saw a collector offering $7000 for a rather large Dynastes satanas,” says the director of Bolivia’s Conservacion Internacional, Eduardo Forno, from his office in La Paz, a chalet surrounded by a flower garden that matches the mission of an NGO dedicated to protecting biodiversity.

Bolivian butterflies are the most expensive: preponas, morphidaes, anneals, and agrias. It is estimated the Andean nation has some 3000 diurnal and 20,000 nocturnal species. The females, more colorful and rare, are the most valuable and difficult to catch. Forno, owner of the largest private collection in Bolivia, assures us there are only ten preponas in collections across the world. Unlike the beetles, which are sold live, butterflies are exhibited, kept and traded while dried and conserved to perfection. A tiny blemish on a wing or a bent appendage can cause the specimen to lose all its value…

Forno’s father, the abstract painter Herminio Forno, was obsessed with insects and had a collection of some 12,000 specimens, 95 percent of them butterflies. Forno keeps them in a room in his own home.

“Sometimes it’s not about the species, but about having one someone else doesn’t have and would like to have,” the Bolivian biologist says…

Dynastes Hercules beetle. Photo: Udo Schmidt

Until a couple years ago, the insect traffickers put out advertisements on local radio stations in Coroico. After the newscast, the station would air commercials with men assuring listeners they would pay a good price for beetles or butterflies with certain characteristics. To contact them, they said, one only had to ask around in the town square.

Authorities thought these commercials were too blatant and they banned them. The business, however, is still visible in the communities, and even in La Paz, one of the country’s tourist hotspots. In hotels and stores they still exhibit and sell dried specimens. Upon arriving in Yolosa, a huge sign announces the transport of illegal chemicals is a crime punishable by prison: Los Yungas is one of Bolivia’s coca-growing centers and by extension one of its biggest cocaine producers. But the signs warning against the consequences of trafficking insects are much less prominent, despite a 1992 environmental law expressly prohibiting their sale or export out of the country.

In Bolivia, South America’s poorest country, other problems like cocaine, money laundering and corruption obscure the illegal insect trafficking. The attorney general’s office has only ever arrested one person for the crime. It was February 17, 2010 when Ericka Cuevas entered the Bolivian national post office bearing two packages she wanted to send to Germany. Employees discovered that the packages contained 8,992 butterflies and beetles in smaller packages. She was sentenced to three years in jail and served eight months after she cooperated with authorities. “It was obvious that she was only an accomplice to the principal offender,” says the prosecutor for economic and fiscal crimes, Magali Gonzalez, who took on the case only after drawing straws: there are no prosecutors here who actually specialize in the crime. Cuevas, a Bolivian, tells us her boss was a Peruvian woman living in La Paz [Bolivia]. By the time authorities located a store and a home in the Peruvian’s name, she had already fled.

“These cases are very rare and many times people do it because of ignorance,” says prosecutor Gonzalez from her small office in downtown La Paz. Here, until just a few weeks ago, she had kept the almost 9,000 insects stacked in display cases. Each one of the specimens was perfectly dried and pinned by the hands of Fernando Guerra, the only entomologist in Bolivia’s judicial system. According to an appraisal, the shipment was valued at some $25,000.

Guerra, a friendly man around 50 years old who is so skinny that people call him ‘Noodle’, has been forced by circumstance to bury himself in laboratories: there are few scientists in the country–but at heart he considers himself a ‘field man’. During our second encounter, in Corioco, he stops every once in a while on the rocky hills to observe the butterflies fluttering around us. He is spry, smiling. During his expeditions, he has discovered new species of insects and suffered dangerous encounters with animals. One day, while working as an assistant biologist, a rattlesnake bit his leg.

“I almost died,” he remembers.

He urinated blood for three days and was half blind for five.

He also met a lot of insect traffickers on his trips, even doing a job for one of them. He and his research partner combed the region to do a study, financed by a trafficker, to figure out how many species could be captured annually without damaging the next harvest. With a lack of official data, the entomologist calculates between 200,000 to 250,000 insects are illegally exported annually.

“The most well known of the traffickers was Tello. He always had a gun and people were afraid of him,” Guerra says.

Up until he broke his leg in a motorcycle accident, Tello, a Peruvian, traveled the country looking for rare specimens to export to Peru.

“Everyone knew him here.”

He finally retired to Tingo Maria, his country’s butterfly paradise. Since then, he has not been seen again in Coroico.

Dynastes Hercules beetle. Photo: Udo Schmidt

Joseph Steinbach, a German scientist almost six and half feet tall, once found himself in northern Argentina studying new species. He was near the border when he tried an extremely sweet orange. When he asked the locals where it came from, they said Bolivia.

‘If there are fruits like this, there must thousands of different species there,’ thought the biologist, who was especially interested in invertebrates. That’s how he made his way to Santa Cruz in 1910. Soon, he turned into the biggest insect collector in the Andean nation.

‘All amateurs and museums looking for looking native insects can contact me with confidence. 20 years of experience allow me to serve my clients with the highest quality: Jose Steinbach, naturalist,’ read his advertisements in English in the newspapers of the day, giving an address in Santa Cruz, where he settled, married and had eight children. All sources indicate that any notable insect collection in the world has at least one Bolivian specimen captured by the biologist.

His granddaughter Ingrid takes a small hummingbird, dried by Steinbach, out of a glass bottle. It’s a bit damaged, but it’s among the last specimens her family has from the [grandfather’s] collection, sold years ago.

“Only my uncle, his oldest son, kept on trading insects. They called my cousins the ‘butterfly hunters’,” says the thin woman as she holds the dead animal in her hands.

The German was a pioneer in a country that had no idea of the value of its own insects. Later came dozens of hunters, traffickers, collectors and fanatics who started the insect trade.

‘I specialize in bright and rare butterflies for collectors, museums and those interested for scientific or artistic ends. Get in touch with me. Hal Newcomb, 804 (Elizabeth Street), Pasadena, California,’ read another ad in a newspaper. People of all nationalities began to discretely arrive to Los Yungas looking for insects. Steinbach worked for everyone. One of his main clients was an American he remained in contact with throughout his life, according to his memoirs. He finally took on what no Bolivian had done, a study of the Amboro park in Santa Cruz. No one dared enter because it was cursed. They said that is what killed him, though it was really a mosquito that gave him malaria.

Since Steinbach’s arrival in the Andean country, a profitable business has arisen from the insignificant. In the communities of Coroico and Caranavi, the latter the epicenter of Bolivia’s butterflies, peasants started to combine coca leaf planting with hunting flying insects. Some plots of land are full of nets and traps. People lose themselves in the fields with bottles of beer, hoping to attract the butterflies, which have a weakness for alcohol.

Paula Romer, a short smiling woman, fell in love with butterflies three years ago. She was first attracted by their color, and later by their wings and freedom. She started working with people from her community, El Chairo, to build a butterfly farm…, a place open to tourists where insects could be bought legally. Until a few months ago, thousands of butterflies flopped around in mesh nets. Today, only a few surround Paula as she walks amongst the bare branches that were once orchids.

“A lot of tourists came,” Paula said, looking at a cage full of dust.

“There wasn’t enough money. People didn’t know how to manage the project or take care of the butterflies. We had a lot of problems in the communities.”

The same thing happened in Santa Rosa de Pacolla, half an hour from Coroico, where they planned to breed beetles.

“We could have sold the insects without damaging our biodiversity. If it were legalized, it would be a good business for the communities,” says Fernando Guerra, who helped train people like Paula. The two projects working in that direction failed. However, now when adults in El Chairo see a child find a beetle…, they explain they can make money with them, something they’ve known in Japan for a while.

A man wearing a white scarf on his head holds a beetle in each hand. The insects, nearly the size of small mice, twist in the air. The Japanese fans yell as they gather around the small wooden base where the Dynastes satanas will fight to the death. Bets are made. Once freed in the ring, the bugs start to fight. One falls and struggles to lift himself under the weight of his huge horn, which has earned him the nickname ‘rhinoceros’. In the video, posted online, a child interrupts the battle, grabs one of the insects and takes his picture with it. People applaud and the bugs return to their fight. They pound each other with six legs until the stronger of the two grabs the other with its pincers, immobilizing it and, from one moment to the other, cutting it in half. The fight is over. People pick up their money. The winning beetle awaits the next tournament, when another dignified opponent arrives from Bolivia, another insect that, instead of being tied to a string, has the chance to make the trip across the world and turn into a hero.

Jose Luis Pardo Veiras and Alejandra Sanchez Inzunza

24 May 2013