They are the ghosts of Bagram Airbase: dozens of men, mostly Pakistani, caught in the now-familiar 21st century American extralegal limbo of military detention. Perhaps they will be released in some final act of fearless post-election lame-duckery by America’s ‘constitutional scholar-president.’ A thin hope indeed.

From Pakistan’s magazine and photographer Asim Rafiqui, portraits from America’s other Guantanamo:

It happened suddenly. Amanatullah had never been to Iraq before. He was hoping that that the trip would be uneventful, and that he, as a Shi’a, would perform the pilgrimage, or ziarat, that he had been looking forward to take part in for so long. After that, he hoped to return to work as a rice merchant in Pakistan.

It was 2004, and U.S. forces had just invaded Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein. He was staying close to Baghdad shortly after the regime had fallen, when British troops raided the house he was staying in, and handed him over to U.S. custody. When the Americans got a hold of him, they could not understand him-this prisoner spoke Urdu-so they sent him to Bagram in Afghanistan. He is still there to this day, and has left behind a wife and five young children. His youngest daughter was born after his detention and has never seen her father. While he languishes at Bagram, he has lost his elder brother and his father and spent countless Eids without his family. Under international law, the U.S. is obligated to release him. The war in Iraq has ended and there is no legal justification to continue to hold him. And yet, he is there, almost ten years later, with little or no progress in his case.

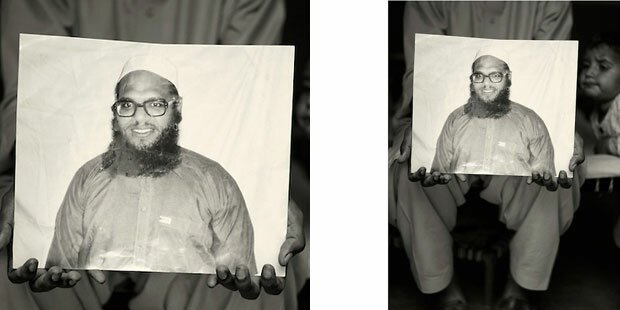

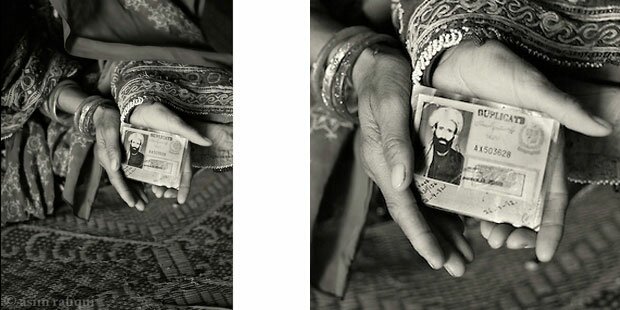

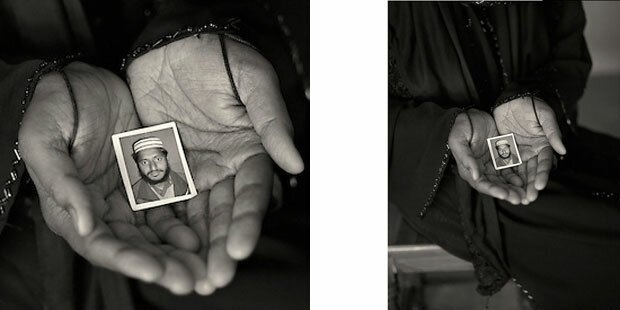

Detainee Hamidullah, photo Asim Rafiqui

I am a caseworker with Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), and we represent Amanatullah and 10 other Pakistani prisoners in litigation before the Lahore High Court. They are just a portion of the 60 non-Afghan prisoners held under U.S. custody in Bagram, Afghanistan. We have no access to their story, except through documents and testimonies that we have collected from the authorities and their families. The reason is simple: The United States does not let us speak to them.

When it comes to Bagram, legal processes meant to be underpinned by ethics of justice are subverted by the powerful. The dominant narrative is that of “security”. We forget that those at Bagram are individuals with lives and families of their own. That is why we, as lawyers, have to step outside our comfort zone: as we continue to fight our battle in the courts, we have no choice but to push this debate into the public realm, and shed light on the injustices at Bagram.

Two weeks ago, JPP released a report that details information on Bagram, and its incarcerated prisoners. The report is based on interviews and case documents, and includes a photo essay by Asim Rafiqui on Bagram prisoners and their families. It is our attempt, as lawyers, to bring the case to light-justice is hard to come by in Bagram.

Detainee Abdul Halim Saifullah, photo Asim Rafiqui

The United States launched its much-reviled Global War on Terror in response to the attacks on 11 September 2001. Despite a planned reduction of troops at the end of 2014, there is no indication that the U.S. plans to wrap up their GwOT anytime soon.-this year the Department of Defense announced that the war could last another 10 to 20 years. It is a grim statement considering the legacy of the Global War on Terror: an appalling detention regime, which has eroded American values for more than a decade.

The erosion began more than a decade ago.

In February 2002, President Bush publicly declared that the Geneva Conventions-regulating armed conflict-did not apply to individuals under U.S. custody suspected of being members of al-Qaida. According to the U.S. government’s interpretation, it would apply to members of the Taliban only if the Taliban government was still in power.

According to the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the law of armed conflict and international human rights law are considered complementary, not mutually exclusive. This means that even in periods of armed conflict, states are bound to respect their human rights obligations.

But the United States does not consider its human rights obligations to extend beyond its borders. According to articles 9 and 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, no one shall be arrested arbitrarily and everyone is entitled to a public and fair trial. Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantees protection from arbitrary detention, and access to a fair trial. In the context of the GWoT, this means that individuals held under U.S. custody outside of American borders have been wilfully and deliberately deprived of any rights whatsoever.

One of the clearest examples of this gross violation is Bagram Prison.

At first, Bagram was used as a screening point for detainees before they were shifted from Afghanistan to Guantanamo Bay. In 2004, legal challenges prevented the U.S. government from transferring anyone to Guantanamo. The population at the prison in Bagram ballooned, giving birth to a second Guantanamo. Thousands languished in Bagram under U.S. custody, until September of last year, when the American military handed over control of 3000 Afghan inmates to the government in Kabul. Today, the U.S. only maintains custody over a small portion of the facility-the part that houses over 60 non-Afghan detainees, 40 of whom are Pakistani citizens. They are currently being held without charge, trial or access to a lawyer.

Detainee Paizoo Khan, photo Asim Rafiqui

In 2009, the Obama administration introduced a review system. The men are presented before a board of U.S. military officers within 60 days of being brought to Bagram Prison. Their case is then reviewed every six months, and hearings are divided into unclassified and classified portions. They can be present only during the unclassified portion-they are not allowed to witness classified hearings, nor can they see the classified evidence held against them.

During the hearings, they are provided with a personal representative. The representative is not a lawyer, nor does he need to be legally trained. Rather, he is a U.S. military officer whose task is to assist detainees before the board. Because of their military status, representatives change according to military deployment cycles. This means that every nine months, the men at Bagram have to trust a new U.S. serviceman to represent them before the board.

The purpose of the review system set up by the U.S. is not to determine guilt. It is merely an administrative process which attempts to ascertain whether a person represents a threat to U.S. forces. This is the Obama administration’s idea of due process: nothing more than a travesty of justice; an opaque system built on secrecy. It is entirely run by the U.S. military and isolated from independent scrutiny or support. The men held at Bagram can rely only on their jailors to get them out.

One ex-detainee called the board hearings a “joke”. For him, it was another way for the U.S. military to “humiliate” detainees. From documents and testimonies that we have gathered, there is a clear indication that detainees do not think that the board reviews serve a purpose. They cannot fathom how they can defend themselves if they are not allowed to see the evidence held against them.

In a 2010 publicly available board hearing transcript, Amanatullah decries the purported independence of the personal representatives. To him, whatever the representative says is “for [the U.S. military’s favour]not for my favor”. He asks the U.S. military to provide him with “any proof” of his involvement with terrorist organizations-that is, if they have any. He continues to claim his innocence but goes unheeded by the U.S. military.

Worse still the U.S. military’s evidence against these men is thin.

Take the example of Umran Khan. He was a truck driver in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, delivering goods all across Pakistan. According to released U.S. military records, he travelled to Afghanistan to go sightseeing in 2005. He was riding a taxi with a friend from his village, and two Afghan men. The taxi was stopped at an Afghan army checkpoint. Afghan soldiers arrested Umran and his friend, the two foreigners, and handed them over to U.S. forces. None of the other men were arrested. Subsequent investigation revealed that there was no forensic evidence or intelligence linking Umran to any insurgent activity. By the U.S. military’s own admission, the “evidence is circumstantial at best, but only marginally linked to” Umran. Every six months he is told that there is not enough evidence to hold him, and that he should be released. But nothing happens. He remains at Bagram to this day, stuck in limbo until the United States decides to repatriate him to Pakistan.

Unsurprisingly, his detention has taken its toll. He has lost much weight, and ex-detainees have indicated that he suffers from depression. His brother is alarmed at the deterioration of his mental health. When he speaks to Umran over the phone, Umran appears distracted and distraught. For the past 8 years, Umran’s sisters have not seen or heard of him. He does not want them to see him in this state.

Detainee Iftikhar Ahmed, photo Asim Rafiqui

The men in detention do not have access to effective due process. It is the result of a militaristic view of international law and sense of entitlement, which sees the entire world as a battlefield and those living in it as potential targets. The current system keeps them at Bagram Prison in a constant limbo, and deprives them of a reasonable opportunity to contest their detention. It allows the Department of Defense to maintain the intense secrecy and opacity surrounding its detention operations in Afghanistan.

Because of the scarcity of information, the Department of Defense can claim that “stories relayed by detainees to a sympathetic NGO reflect all manner of claims that simply are not supported when real, intellectual rigor is applied.” But what truly lacks “intellectual rigor” is the assertion that the men at Bagram Prison are “too dangerous to let go”, as U.S. officials and Congressmen would have us believe.

We only have their word for it. What little unclassified evidence exists is far from conclusive. Anything else is not open to public scrutiny. There is strong reason to doubt the veracity of these claims. When it comes to GWoT detention, the Department of Defense has not been a shining example of truthfulness.

They claim that all the men held at Bagram Prison were detained for “enemy actions” in Afghanistan. At best, the spokesman making such a claim was ill-informed. At worst, they are lying. Amanatullah Ali is just one case of a man captured outside Afghanistan. Yunus Rehmatullah, a 31-year old Baloch man, was captured alongside Amantullah in Iraq. In 2012, the UK Supreme Court said his on-going detention could constitute a war crime. In blatant disregard for international law, the U.S. is still holding Yunus.

There are also men who were kidnapped in Pakistan and transferred to the U.S. authorities. Abdul Haleem Saifullah used to live in Karachi where he worked as a labourer. In 2004, he disappeared after dropping his ill father off at the hospital. He was only 19. His family suspects he was kidnapped by Pakistani intelligence agents and sold to U.S. authorities in exchange for a bounty. Such a practice was common at the start of the GWoT. His father passed away shortly after his disappearance, stricken by grief.

The Department of Defense also has a tendency to grossly overstate the security risk they think detainees will pose upon release. They call this risk “recidivism”. “Recidivism” is a term of art in criminal justice used to describe a person who repeats an offence. Their choice of words are misleading.

First, certain detainees have been released because it was deemed that they were never combatants in the first place. This means they have never conducted any hostilities against the United States. It is an impossibility for them to repeat an offence they never committed. Second, detainees are not tried and convicted. There is no criminal justice system at Bagram or Guantanamo Bay. In no sense can they ever be “recidivists”.

In 2010, the Department of Defense claimed that 25 percent of the men released from Guantanamo Bay returned to threaten U.S. national security. The New America Foundation debunked their claim, bringing the number down to 6 percent. Most recently in January 2013, they claimed the “recidivism” rate to be at 16 percent. Again, the New America Foundation put that number much lower, at 4.7 percent.

Detainee Fazal Karim, photo Asim Rafiqui

In the eyes of the Department of Defense, the men at Bagram are not human beings. Amanatullah Ali is not a 40-plus, father of five. He is Internment Serial Number (ISN) 1432. Umran Khan is not an easy-go-lucky truck driver from Khyber Agency. He is ISN 2422. They are statistics feeding into fear-mongering propaganda. These men are “threats” who must be “assessed” and disposed of.

In his opening statement before the Nuremberg Tribunals, Chief Counsel for the United States Robert Jackson said: “That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.” His was a tribute to due process and respect for the rule of law, both long-standing American values.

Today, Bagram Prison serves only to prove that the United States is not genuine about its respect for international law and human rights. It reminds us all that the United States picks and chooses which norms to follow, according to political convenience.

The situation can be resolved. The United States must allow the men at Bagram access to legal counsel. It must provide a fair and open trial to those against whom there is sufficient evidence. It must negotiate a comprehensive agreement with Pakistan to ensure they return home before the U.S. military withdraws from Afghanistan.

Only then will this injustice end.

Omran Belhadi

08 Jan 2014