Julian Assange’s lengthy and thoughtful interview with Mexico’s La Jornada continues. Are the attacks on Wikileaks, and the zealous American pursuit of leakers-Bradley Manning, Edward Snowden, John Kiriakou and others-a game of securitization by the establishment, or are they outgrowths of a real fear of the democratization of access to information?

Part II:

Something is amiss when the Pentagon, which should be projecting itself as mighty, starts playing the victim. So says Julian Assange, regarding the reaction of US officialdom to the Wikileaks revelations of 3 years back. The Australian ponders the power that new information technologies can give to common citizens, describing them as the most important instrument of mass political education that has ever existed.

The traditional American media, he says, has always been very corrupt, and have now given up their task of scrutinizing the behavior of the powerful: they have become nothing more than arenas to settle conflicts between differing factions of the regime.

Our conversation with Wikileaks’ founder takes place in the tranquility of the Ecuadoran embassy in London, in a comfortable salon with high windows overlooking the street. At some point a muted rumble intrudes. The interviewee cocks an ear, interrupts the conversation with a courteous gesture, and walks toward the balcony. On the opposite sidewalk, a small group is raising placards of Assange’s face, chanting slogans for his release. The refugee opens the curtain and waves to his sympathizers with a gentle, almost shy wave of the hand, and signs the ‘V’ for victory with his fingers. He remains there for a few moments and then returns to the monumental sofa.

The greeting is part of his daily routine since the 19th of June of last year, when he entered the Ecuadoran diplomatic mission, asked for political asylum, and left his American, Swedish and British pursuers in the dust. Thus began a diplomatic dispute, in which Washington will not recognize its own role, leaving London and Stockholm to do the dirty work of refusing to recognize the right of political asylum. This week the impasse will be a year old, and the Ecuadoran chancellor Ricardo Patino will travel to the British capital to try to resolve the conflict, seeking to obtain from his British counterpart a safe-conduct permitting the Australian to leave the United Kingdom for Ecuador.

“At one point they stood guard outside 24 hours a day,” says one of Assange’s associates, in reference to the fans who are shouting their support outside. They still come every day.

The conversation is interrupted again later, when Assange’s associates bring in the first reports of former CIA employee Edward Snowden’s leaks about the enormous and illegal network of telephone and internet espionage erected by US military intelligence (the National Security Agency).

Julian Assange’s reaction: “It is interesting to see this recent revelation-it is something we have been talking about for years-but now we have very solid evidence about it. An order to spy on all telephones, every day; where people are calling from, who they call, what kinds of telephones they have, and everything is sent to the NSA every day. It is such a vast invasion, it includes every reporter, every office, it includes everyone. It is an enormous violation of… which amendment, the Fourth? Anyway, it is a violation of the constitutional protection against searches and seizures, a violation as huge as you can imagine.

La Jornada: In 2010, Wikileaks made three enormous and devastating revelations of US documents, many of them secret until now: those about the wars in Iraq and Iran [Afghanistan SIC?] and the State Department cables.

Julian Assange: The Pentagon’s reaction was to play the victim, say that it was deeply injured and worried. We saw Robert Gates [US Defense Secretary between 2006 and 2011] almost on the verge of tears, and this seems to have been a reflection of the state they were really in: their sins had been exposed. They knew that we still had a lot of material which was still unpublished, hundreds of thousands of classified documents, they hadn’t read them all yet, they did not know what kind of impact they might have, they were terrified before the unknown and in the United States they launched a sort of neo-McCarthyan witch-hunt [against leakers]that has ended up extending to the rest of the world. It was very interesting to observe.

So now: the Pentagon is an organization that specializes in appearing strong and powerful so that its threats carry weight. Basically the Pentagon is a device for blackmail: it threatens to physically dominate countries, or alternatively remove its protection from them, leaving them open to the domination of a third country, or perhaps it involves itself in the sale of arms to neighboring countries, and threatens others with ceasing to sell them arms. So [the American military]is a tool of intimidation, of applying threats to obtain concessions from numerous countries and institutions, and for that reason it needs to appear powerful all of the time. But if your mafia enforcers start playing the victim, that means the mafia’s racket is not working. So in short, they were terrified.

Furthermore: there is a concept in critical theory, not well known, but very useful, which is known as securitization. I’ll put it in my own words: we are all motivated by the fear of, or desire for, something; essentially fear and desire make us want to either recoil or move forward… At one extreme, fear completely dominates hope and desire; you are in fear is of losing your life or the lives of people you love…

If we translate this from a psychological level to a political level, an institution takes a situation and tries to extract value from fear, and this is what is called securitization: transform a situation into a threat to security, and later propose that the institution can save you from the threat. Okay. Securitization is what the Pentagon does every day: look for any situation in the world that can be securitized, and say that the solution to the fear is protection by force of arms. In a similar way the police try to this in every circumstance: the solution to murders, robberies, spying, fraud and some forms of terrorism is a strong and aggressive police force.

So I have to ask myself: this assault on Wikileaks, with Hillary Clinton saying that our publications were an attack on the United States and on the entire international community; with the public and private attacks by the Pentagon and the State Department and many other organizations, were they just securitizing the situation? Trying to attract more resources, terrorize the establishment so they would give up more money [to these security institutions]? There was an element of that, but they were also themselves terrorized about the dawning of a new public perception about their own power.

La Jornada: An interesting coincidence: the American authorities were playing the victim and inventing or exaggerating the damage caused by Wikileaks; and then this same year, Fidel Castro, after the publication of the Iraq War Logs, said in interviews [with Jornada and Telesur]that we were standing before the most powerful weapon that had ever existed; communication, and that with it, armed revolutions are no longer necessary, and that Wikileaks deserved a public monument. Was he exaggerating?

Julian Assange: A bit. It is nice to hear words like that, but…everything starts with the truth, and without the truth there can be no further steps. In the end, everything comes down to who has the monopoly of force over a given piece of land where people live.

Your email is stored with Google. You may think your personal correspondence with other people is an important part of your life. But if it is stored on servers in California, where Google has its headquarters, the courts in California, the federal courts, the US central intelligence agency, control it. Even so, physical coercive power is important. And who controls the police and soldiers? … […]

Going back to Fidel Castro-we are now in a position where, thanks to advances in military and police technology, the difference between a campesino with a rifle and a policeman in his Kevlar armor is so huge that it is not easy to imagine armed insurrections without the aid of a state. George Orwell wrote an article in 1945, just after the bombing of Nagasaki, comparing the different types of military technology. Rifles, anyone could have them; they were a very democratic military technology. If you have more people you have more rifles in action. And so military success is quite closely related to how many people you have. But at the other extreme, only a few states are capable of building nuclear weapons, because very large and centralized industrial processes are needed, so it is an essentially anti-democratic form of military technology.

La Jornada: But these days many people have access to the internet, just as almost anyone has access to a rifle.

Julian Assange: In contrast to advances in military and police technology, which consist of very anti-democratic power, there is the horizontal transmission of information: almost anyone who knows anything can communicate it, at least in theory, to everyone else, although distribution and publicity networks may interfere. The most important instrument of mass political education that has ever existed has been created. The number of people exposed to it, the number of cultures, the number of languages, the geographical connections, are largest of any moment in history.

The key transition came as a result of the attack against Wikileaks and its publications. If you go back four years, basically the internet was politically apathetic. You had small networks and some political groups using it, but as a whole the internet was politically apathetic. And people could watch in real-time the war against Wikileaks. Even if you were not on the front line, even if just from the margins, witnessing the claims and counterclaims, the action, allowed a comprehension beyond a lesson or reading of history. With our geopolitical fight against the US and its allies, we educated a whole generation on the internet, woke it up to the geopolitical realties of the world, and woke it up to the fact that the internet is a political space, rather than simply a space for communication like the telephone system.

La Jornada: A battlefield…

Julian Assange: A battlefield yes, but not a distant battlefield, its is a theater of operations which people are part of, you yourself as well. If we are going to talk about individual contributions, I think this is the most important one from Wikileaks: transforming the internet from a politically apathetic space into a political space, and in the process educating basically a whole generation. Even people who are sixty-something years old have told me: ‘because I saw what happened, nowadays I see the world differently.’ But especially people between 16 and 28 felt that they were part of this political drama that was playing out. And many of them were a direct part, because they distributed information, took part in virtual protests. Young people were interested, they read what the media were saying about us, and later read what we were saying, or read the cables, or what their friends were saying by email, and saw a completely different point of view, and trusted our point of view more because it was based on primary-source documents, which do not lie.

La Jornada: What good is the truth, Julian? To make political systems function better, or to put an end to them?

Julian Assange: Do you want a poetic answer, or do we go at it from a different point of view? [Laughs] The truth is all we have. There is no hope with anything else. Every action, every decision, every thought we have, is based on what we perceive, but it acts on our shared reality, on the real world. So if we are not thinking the truth, we are not thinking about the world that we must actually act upon. If we do not take action based on the truth, our possibilities for action in the real world are just random.

And what makes truth? Blowing up political systems or permitting their reform? Either of these things can happen, depending on the extent to which they are based on truth or not. If they are principally based on lies, if the truth has failed, it will be a catastrophic collapse (although there were other factors as well) such as happened in Tunisia or Egypt. It seems to me that systems [based primarily on lies]get to such a bad state that they collapse. You have to put them in a position that they have to expand so much that they go over the edge… Some of these systems can patch themselves up. On the other hand, maybe when you get to the point where you can overthrow them, maybe it doesn’t happen, or perhaps they expand more, get more dangerous, more powerful and corrupt. […]

La Jornada: Is what people call the Fourth Estate collapsing in the US?

Julian Assange: The rise of alternative media, especially on the Internet, has allowed us to see how corrupt the media that are part of the system really are. Okay: can the Internet be a resource for making them less or more corrupt? I am not so sure. On the one hand, when corruption, errors, lies or propaganda exposed, the reputation of traditional media is affected, and so independent information can act as an incentive to make them behave better. But on the other hand, the market for criticizing the powers-that-be is now better taken care of by new publications, so the conventional media feel freed of the responsibility to do this task; they feel that others have taken that business away from them and don’t feel the need to keep doing it. In any case, remember that they cannot do it very well; traditional media have always been involved with one faction of the system that is criticizing another. They have never been in the business of being critics of the establishment per se. They have always been very corrupted.

Let’s look at the case of the New York Times: we know that in 2003, there was a story similar to Watergate, about illegal wiretaps; the New York Times sat on the story for 18 months so Bush could be reelected. They only published their story when a rival publication was on the point of letting the cat out of the bag. An institution like the New York Times is, absent the quality of certain journalists, an arena for different factions of the system to struggle among themselves in public, or for them to publicize their own positions.

That is why people like to read it, not because it is more accurate than other newspapers. It constantly commits important errors and even publishes fabricated stories; it for example said that Al Qaeda had weapons of mass destruction. Why do people still bother to read it? Because what powerful people say is interesting. If Obama or the CEO of Bank of America, or Schmidt, from Google, suddenly claims that the Martians have landed, without any evidence, it is very interesting because it represents something about the declarers themselves, about their position. Everything that has to do with a powerful organization is by definition interesting, because it can have an effect on the world. So people read the New York Times to see the position of various factions of the regime. This has always been the case.

Let’s go back to 1917, when Eugene Debs, an American socialist agitator, was accused under the Espionage Act, the same they are trying to apply to me, of having called for draft resistance in World War I. Debs only said that the mandatory draft was bad, and that people should oppose it. Well, the New York Times in its editorial called for Debs to be tracked down and arrested, and indicted under the Espionage Act, for giving a speech. So in that sense, nothing has changed.

Part III:

The sun has finally agreed to warm this London afternoon, and Julian Assange seems relaxed. Amidst the judicial, financial and propaganda harassment, carrying around his neck the hostility of three governments, among them the most powerful one on the planet, demonized by all and sundry-there are the Western right-wingers accuse him of being a terrorist, and there are no lack of mad voices on the left that see Wikileaks as some kind of CIA plot; ready to compete in the field of intelligence with enormous institutions of espionage and repression; forced to choose between a billiard-game of extraditions that might end in a trial in Alexandria, Virginia, or imprisonment in the embassy of a distant though friendly country, Julian Assange remains calm. There is no crazy optimist in him. On the contrary, his perception of the current state of the planet is rather somber:

Julian Assange: The end of the Cold War and the classic ideological struggles left us in a position where the entire Earth is now steeping in a single ideology, the West’s, and we cannot see beyond it. Some thinkers believe they are moving in a different current, that they have some kind of perspective, but this is impossible.

[…]

The first thing that has to be done is change the system of knowledge, the flow of information and education. I figured that out a long time ago, and that is why I did not get involved in politics, but started with Wikileaks: because to making information known, publishing primary-source documents, make life difficult for institutions that live on secrets, these are things that change the media environment, the knowledge environment.

People need to see hope. To get good people involved, you need to show them that a certain activity will accomplish something, and to do that you need ethical motivations. But in the end, everything comes down to how well you understand the political situation. If we go back to the classic Marxist description, people need to recognize their own class and position. If individuals do not recognize that they are in it together, under particular conditions, there is no hope to accomplish anything. […]

I have always thought that politics, as it is traditionally done, does not raise hopes.

La Jornada: Despite that, you are running as a candidate for the Australian senate, and you are forming a political party in your home country:

Julian Assange: And according to polls in Australia right now, we have 40-percent support among people under 30 years old, despite its being the first election we are contesting.

La Jornada: Okay. But now you are in the struggle for power. A political party is a tool in the struggle for power.

Julian Assange: A kind of power, yes, but in essence it is the same kind of power Wikileaks has been struggling for: the power to reveal, to bring the truth into the light.

La Jornada: You want to win an election.

Julian Assange: Yes, but not to form a government. We are running for seats in the Senate, which is the chamber that monitors, its functions is to keep an eye on the government, make its functionaries testify. In Australia, we do not have the post of president, so it does not matter how popular I am, I could not win. We have a prime minister, but he is elected by the parliament. So we would have to arrive at a position where we controlled more than half of parliament. Maybe in a few years but not in this one.

La Jornada: Julian, when you found a party and contend an election, you always run the risk of coming into power.

Julian Assange: Yes [laughs]. But in this election, we would achieve a position of relative power, between one and three senators. This is relatively powerful, but a small amount of power compared to what Wikileaks already wields as an organization.

Often Australians call themselves, with scorn, ‘the 51st state.’ But it is the truth: Australia is a state of the United States without the right to vote. We have a president, Obama, whom we did not vote for. Once you recognize this-it’s something I realized 10 years ago-you realize that you have to interact directly with the Empire. You have to interact directly with the great center of power. You cannot take the attitude that ‘I am going to just look out for myself.’ The important thing is the Anglophone alliance, what we maybe should call the Western Empire: the alliance of the US, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

It is an alliance that shares intelligence: many official US documents are classified as Secret/NoFORN. What does NoFORN mean? It means no foreigners, that is, the document is off-limits to any citizen of even close allies of Washington, like Germany or Italy, whether an intelligence agent or an employee of NATO.

But a regulation recently approved by the US intelligence services holds that the citizens of Great Britain, Australia and Canada can have access to NoFORN documents.

On Wikileaks we revealed an enormous high-tech joint military intelligence exercise which involves the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain, which is carried out annually: it is called Operation Empire Challenge. If anyone does something annoying, all of their spy satellites can communicate between one another, in addition to the airplanes and the troops of the 5 countries, to confront the situation. That is how internally the Empire organizes and conceives itself. So the point is: moving Australia politically, is an important way to politically move the Empire, because Australia is part of it.

La Jornada: That is a way of looking at things. But right now it appears to me that you are the person who has suffered the most extreme international political persecution since Leon Trotsky [who was eventually murdered by Stalinist agents in Mexico City, not far from La Jornada‘s newsroom].

Julian Assange: I am not so sure about that comparison, (Assange grumbles). Where you are probably right is that in Trotsky, the Kremlin saw a similar kind of threat that the Western Empire sees in me: as much a symbol as a real leader. And in both cases we are talking about perceptions.

What is the real threat that I represent for the Western establishment? And what real threat did Trotsky represent for the Soviet Union? It is difficult to evaluate. But in the end, if there is a broad perception of a threat, then there is a threat. It’s a little bit like football [soccer]: What does it really matter if one team or another wins? It doesn’t change anything really. But for a ball to matter, all you need is for a lot of people to think it does.

La Jornada: In any case, you are a ball that is living on the run. And under threat.

Julian Assange: There was a threat to assault Ecuador’s embassy by the British government. There were policemen coming down on rappelling lines, this embassy was surrounded by police early that morning, and it received a formal written threat. The anger at the attempt at violating the embassy’s sovereignty made the British government pull back, and they won’t try to do that again. They may try other types of attacks but they will not try to assault the embassy. They can huff and puff as much as they want. The reality is that Ecuador studied the situation and gave me political asylum

La Jornada: some, in the pro-Western media, have said it is a paradox that you have asked for asylum from a government accused of repressing the freedom of expression.

Julian Assange: There is no paradox. It would be a paradox to ask asylum from a country that does not offer asylum. Nobody makes judgments like that about someone who asks for asylum in the United States; they do not say ‘how can you ask for asylum from a country where the rule of law has collapsed, etcetera.’

In fact, more than a few of international attacks on Ecuador’s reputation in terms of freedom of expression are simply attempts to tarnish me, and in those cases, the Ecuadoran government is nothing but a collateral target. …My asylum has nothing to do with that, and moreover I am not a spokesman for the government in Quito. For the rest, these claims that Ecuador has journalists in prison, that Ecuador routinely sends journalists to jail, they are false.

Take the case of the Committee to Protect Journalists, a conservative group in the US, founded by the official press, or Reporters without Borders, they keep the lists of imprisoned journalists in lots of countries, but in Ecuador the number is zero. In Turkey there are 48. Or take a look at Freedom House, founded by the government of the US. Every year they make rankings for freedom of the press. They have three categories: ‘free,’ ‘partly free’ and ‘not free.’ Of course they classify the US as free, along with Britain and Sweden; that’s how they classify the majority of Western countries. Before I went into the embassy, Freedom House put Ecuador as partially free; once they gave me refuge, Ecuador was reclassified as ‘not free.’

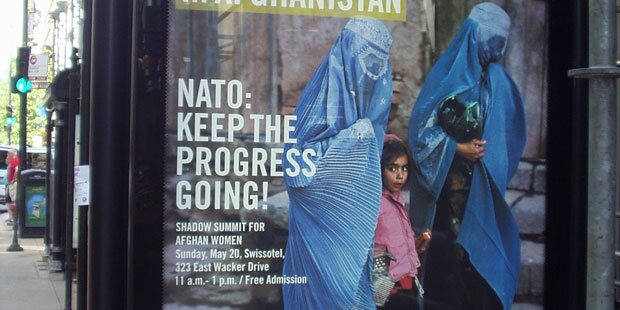

In the case of Human Rights Watch, if for certain they have done good things, as in the case of Bahrain, they go too far in the case of Russia or in the cases of Venezuela, Ecuador and other countries. This reflects their personnel and their financing. Let’s take a look at their personnel: their chief of Global Initiatives, Minky Worden, worked before as a speechwriter for the US attorney General. And three months ago, her husband, Gordon Crovitz, demanded in the Wall Street Journal, that I be indicted for espionage… Last year Amnesty International hired Suzanne Nossel, a longtime functionary of the State Department, and who has published billboards actually supporting NATO’s presence in Afghanistan.

Amnesty International billboard for Nato occupation of Afghanistan.

Amnesty, like Human Rights Watch, has refused to recognize Bradley Manning as a prisoner of conscience. The definition of a political prisoner, according to Amnesty’s own directives, is that the supposed offense be of a political nature, or that the prisoner’s action was carried out with a political intention, or that the investigation has been carried out for political reasons, or that the investigation is politicized, or the imprisonment is politicized. It is indisputable that Bradley Manning falls under the majority of these conditions, but nevertheless Amnesty has told us that they are not even going to take the trouble to determine if Bradley Manning might be a prisoner of conscience or political prisoner, until he is sentenced. What good will it do then? When these organizations see which way the wind is blowing, and when Manning is in prison facing a life sentence, or a death sentence, only then, and only if they can get some kind of political benefit from it, would they declare him a political prisoner, but not before.

So these organizations are bankrupt and in general cannot be trusted. If you look at what they say about a country that is not in one camp or the other, like for example Equatorial Guinea, then maybe you can trust what they say. But if they talk about Bradley Manning, or about Ecuador, Russia, or the United States, their agendas are too slanted.

Amnesty was a grassroots organization; it once got most of its financial support from society, but that has all changed. When an organization accepts funding from governments, or from establishment organizations like the Ford Foundation or the Rockefeller Foundation, who are its real interlocutors? When Amnesty issues a press release, is it for the public or for those who finance it? In sum, it is about corrupt organizations and we need to see where they get their money from and where they recruit their people from.

La Jornada: What is your biggest satisfaction of the past three years?

Julian Assange: Well, I suppose every day is a political satisfaction.[…]

A big satisfaction has been keeping our people from getting arrested, detained or jailed, keeping the organization functioning, keep it from going bankrupt. We have not fired anyone from the team for financial reasons, although people have had to adjust to salary reductions of 40 percent, as a result of the financial blockade. They have not dismantled the organization, they have not been able to put any members of our team in prison yet. And although I am in a difficult position, I have been able to keep working.

If someone told you that a small, radical publisher was going to take on the White House, the CIA, the Department of Defense, the Pentagon, the NSA and the FBI, what chance would you give it to still exist three years later? You would say none at all. But here we are, and that is a satisfaction.

Pedro Miguel

03 Jul 2013